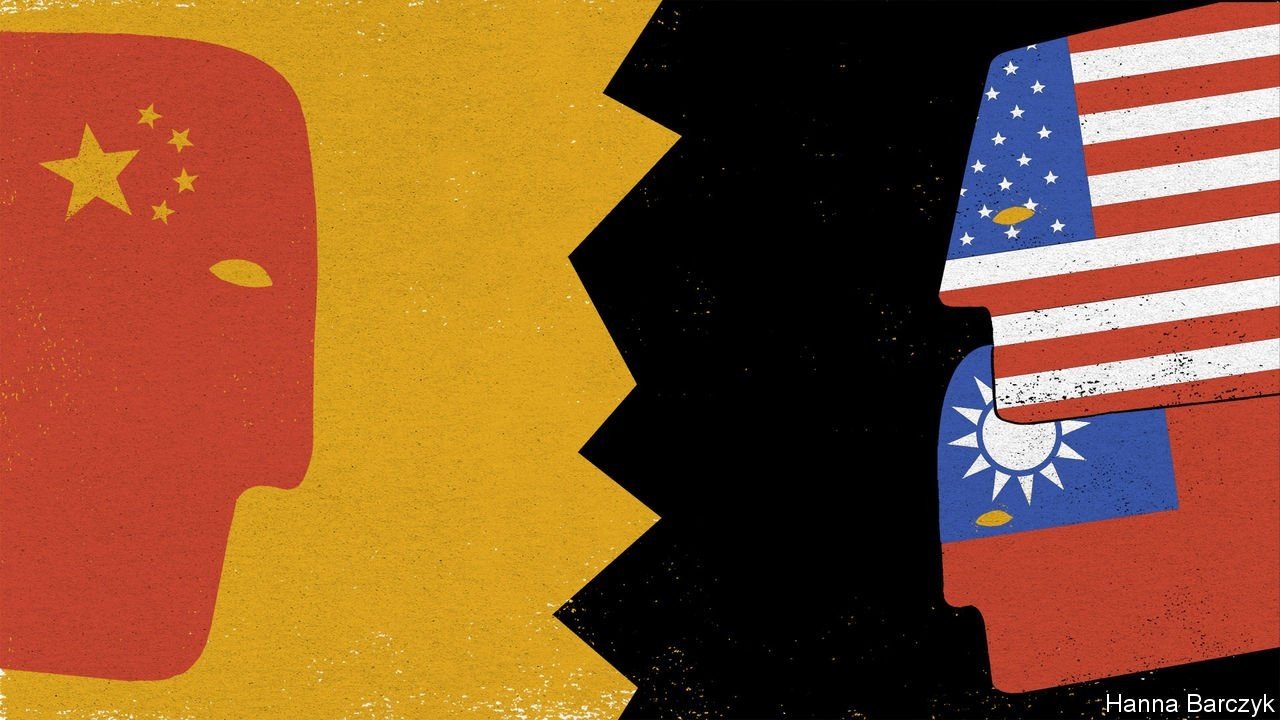

Chaguan – China faces fateful choices, especially involving Taiwan

C HINA’S RISE involves some fateful decisions for President Xi Jinping, the country’s leader. None matters more than whether to attack Taiwan, to bring that democratic, pro-Western island of 24m people under Communist Party control. If, one day, an armoured Red Flag limousine carries Mr Xi as a conqueror through the streets of the island’s capital, Taipei, he will become a Communist immortal. He will join Mao Zedong as co-victor of a Chinese civil war that was left unfinished in 1949 when the defeated Nationalist regime fled to exile in Taiwan.

Listen to this story Your browser does not support the

Perhaps Mr Xi will ride through Taipei streets still scorched by fire, stained with blood and emptied of ordinary Taiwanese by the diktats of martial law. But Taiwan’s conquest would still mark China’s elevation to the ranks of powers so mighty that no single country dares to defy their wishes. To the hard men who rule China, history is not written by the squeamish. Should Mr Xi order the People’s Liberation Army to take Taiwan, his decision will be shaped by one judgment above all: whether America can stop him. For 71 years Taiwan’s existence as a self-ruled island has relied on deterrence of Chinese aggression by America. True, Taiwan also benefited from a degree of Chinese patience, as China tried other gambits that might avoid war.

Since the days of Deng Xiaoping, Chinese leaders have been binding Taiwan to the mainland economically. They have also tried to woo the Taiwanese public with promises of autonomy should they accept rule from Beijing, under the rubric of “one country, two systems”. That concept was transformed last year from dubious to empty by the crushing of civic freedoms in Hong Kong, a territory that was offered similar promises. But China is losing patience with “peaceful reunification”, and colder calculations have always mattered more. At root, China stayed its hand for fear that Taiwanese troops would hold it off until American rescuers arrived.

America’s centrality to this stand-off is well-known to President Joe Biden and his foreign-policy aides, who are an experienced bunch. That is why, on the Biden administration’s fourth day in office, the State Department rebuked China for military, economic and diplomatic attempts to intimidate Taiwan, and declared America’s commitment to the island to be “rock solid”.

In reality America’s ability to deter an invasion over Taiwan is crumbling. The main reason is China’s single-minded pursuit, over 20 years, of the advanced weapons and skills needed to keep American forces at bay. Another is Mr Xi’s sense of historical destiny, and his use of populist nationalism to bolster his authority—though nationalism also raises the costs of a botched attack. In some forums, American scholars and retired high officials have praised the Trump administration for approving more than $17bn in arms sales to Taiwan. They have also scolded Trump aides who used showy support for Taiwan as a way to provoke China, without thinking through risks to the island. Some scholar-diplomats, such as Richard Haass of the Council on Foreign Relations ( CFR ), have urged America to end its policy of “strategic ambiguity”, which avoids making explicit pledges to respond to aggression against Taiwan. This vagueness is meant to discourage rash moves by Taiwanese politicians and avoid enraging China.

Bonnie Glaser, an expert on Chinese and Taiwanese security at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a think-tank in Washington, says that the Biden administration is showing resolve when talking about China and Taiwan, because it is “very worried about the potential for accidents and miscalculation”. It is sobering to hear Ms Glaser, a well-connected scholar, express concerns about accidental clashes today, for instance between Chinese and Taiwanese aeroplanes or boats, and about the possibility of a deliberate military conflict five or ten years from now.

Robert Blackwill, a former national-security aide to George W. Bush and co-author of a new paper by the CFR , “The United States, China and Taiwan: A Strategy to Prevent War”, wants America to create credible “geoeconomic deterrence”, as well as to shore up the military kind. He says America, and allies such as Japan, should make clear that China will be expelled from dollar-based financial and trading systems if it attacks Taiwan. Should Chinese commanders urge war, “we want the economic principals in the room” to spell out the costs, says Mr Blackwill.

Asians will miss America if it leaves

Alas, the hardest part of deterring China involves building robust coalitions that are ready to challenge Chinese aggression. Comparisons with the cold war do not capture the problem. West Berlin’s survival was seen as a vital national interest by America and its NATO allies, who planned for war to stop the Soviets cutting access to the city. But it matters that the Soviet Union was an economic pygmy. Today, there is no consensus among America’s regional allies that Taiwan’s survival is a vital interest over which it is worth angering China, often their largest trade partner.

Meanwhile Chinese leaders are trying to reduce their country’s vulnerability to external economic pressure. In an article last May, Qiao Liang, a retired air force major-general, predicted that in a war over Taiwan, America and its allies would block sea-lanes to Chinese exports and imports, and cut China’s access to capital markets. General Qiao duly endorsed Mr Xi’s moves to reduce China’s dependence on economic demand from the rest of the world. He added that the key to the Taiwan question would be the outcome of China’s contest of strength with America. The general is a nationalist provocateur, but his comments reflect the views of many in Mr Xi’s China. That should give American allies pause for thought. To many Chinese, Taiwan’s recovery is not just a sacred national mission. Its fulfilment would also signal that American global leadership is coming to an end. If China ever believes it can complete the task at a bearable cost, it will act. ■