Interpreting China’s Policy Toward the Russia-Ukraine Crisis

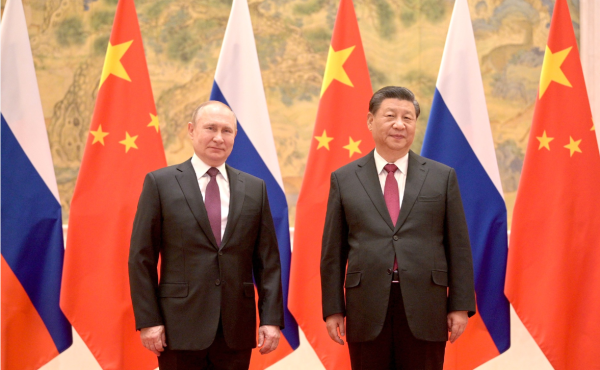

China and Russia came under increasing Western pressure in recent months for their domestic human rights abuses and attempts to forcibly revise the international order. In early February, Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, issued a joint declaration opposing the U.S.-led alliances of NATO and AUKUS, which respectively threaten Moscow and Beijing’s security interests. However, as the Russia-Ukraine crisis deteriorated in late February, with Moscow on the precipice of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Chinese officials at the Munich Security Conference and U.N. Security Council appealed for calm, diplomatic dialogue and even respect for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Beijing is walking a tightrope now with Russia’s declaration of war against Ukraine. Despite warm bilateral relations in recent years, China has kept a distance from Russian territorial ambitions and support for separatist polities in Eastern Ukraine. This article assesses the logic behind China’s stance regarding the Russia-Ukraine crisis by examining determinants of Chinese policy. In the end, China seeks to maximize its interests in a time of conflict between Russia and the West, while simultaneously aiming to minimize harm to China’s economy and security.

Putin frequently referred to Russia’s historical claims when justifying his aggressive policy toward Ukraine. Indeed, history continues to influence policymakers everywhere, including Beijing. China’s current generation of political elite, who came of age in the 1960s, must remember when the Soviet Union was China’s archenemy and the stormy episodes of Sino-Russian relations taught in Chinese schools. Any level-headed expert on Sino-Russian ties knows the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union supported numerous separatist and regionalist forces to advance Russian interests in China.

The Russian Empire-backed Uryankhay Republic broke off from China in 1911, became a Soviet satellite state and was annexed by Moscow in 1944. Similarly, the Russian Empire and Soviet Union supported the Mongolian independence movement that turned Outer Mongolia into a Soviet satellite. In 1944, Moscow supported the Ili Rebellion and Second East Turkestan Republic that sought to wrestle control of Xinjiang away from the Republic of China National Government. Besides separatist movements, the Soviets also invested in other political projects such as regional militarists Feng Yuxiang, Sheng Shicai, Sun Yat-sen’s Guangzhou Government and the Chinese Communist Party, as vehicles to promote Soviet interests in China. The Soviet invasion of Xinjiang (1934) and occupation of Manchuria (1945-1946) both succeeded in strengthening its Chinese proxies.

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

While the chance of Russia using the same tactics against today’s China is just about nil, a foreign country’s blatant support for separatist movements in a sovereign country – particularly through military intervention – is problematic for China given its own separatist challenges in Xinjiang and Tibet (and to a lesser extent Hong Kong) as well as its staunch opposition to any move toward “Taiwan independence.” Thus, past experiences make China weary of Russian utilization of separatist movements as an avenue to military intervention, which sets a negative precedent that could harm Chinese interests down the road.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Despite being characterized as an alliance of two ideologically complementary authoritarian regimes, China and Russia are separate countries with distinct interests. For Beijing, which has been the primary target of Western pressure in recent years, Russia’s sudden move on Ukraine would solve China’s conundrum by forcing the West to shift its attention to Europe. Thus, the best-case scenario for China is the West and Russia at daggers drawn, which allows Beijing the space and time necessary to cultivate its power and influence. Such considerations will guide China’s policy in the near and long term.

As the Russia-Ukraine crisis becomes a war, Beijing has no interest walking into Western crosshairs. At recent international forums, Chinese diplomats have been giving balanced and succinct statements to assuage Western concerns that it might initiate military operations against Taiwan while Russia undertakes military operations in Eastern Ukraine – a nightmare scenario for the West. Yet, China is also avoiding direct criticism of Russia to steer clear of upsetting an erratic partner, which happens to be useful at the moment in diverting Western attention away from Asia. Thus, Beijing is trying to not lean toward either side because the conflict between the West and Russia is beneficial for China seeking to build up its strength. This position will likely be maintained, despite the difficulties in doing so, as Russia carries out its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The conflict between the West and Russia due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, will dominate global affairs for the remainder of 2022. In the foreseeable future, China is poised to benefit from tensions between Western capitals and Moscow. Consequently, it is in Beijing’s interests to see this conflict continue. The crumbling of Russia’s relations with the West and imposition of Western sanctions will further push Moscow into Beijing’s orbit and allow the latter greater leverage and influence in the relationship. In this regard, China has likely prepared measures in response to Russia’s search for economic assistance.

However, China will not move with Russia against the West and will further distance itself from Russian aggression toward Ukraine, as it hopes to extend an olive branch to Europe that could disrupt the united front between the United States and Europe, which has been increasing the pressure on China. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine commencing, China is observing the shattering of European peace closely while contemplating how best to maximize its interests by playing both ends against the middle.