Jack Kerouac: still roadworthy after 100 years

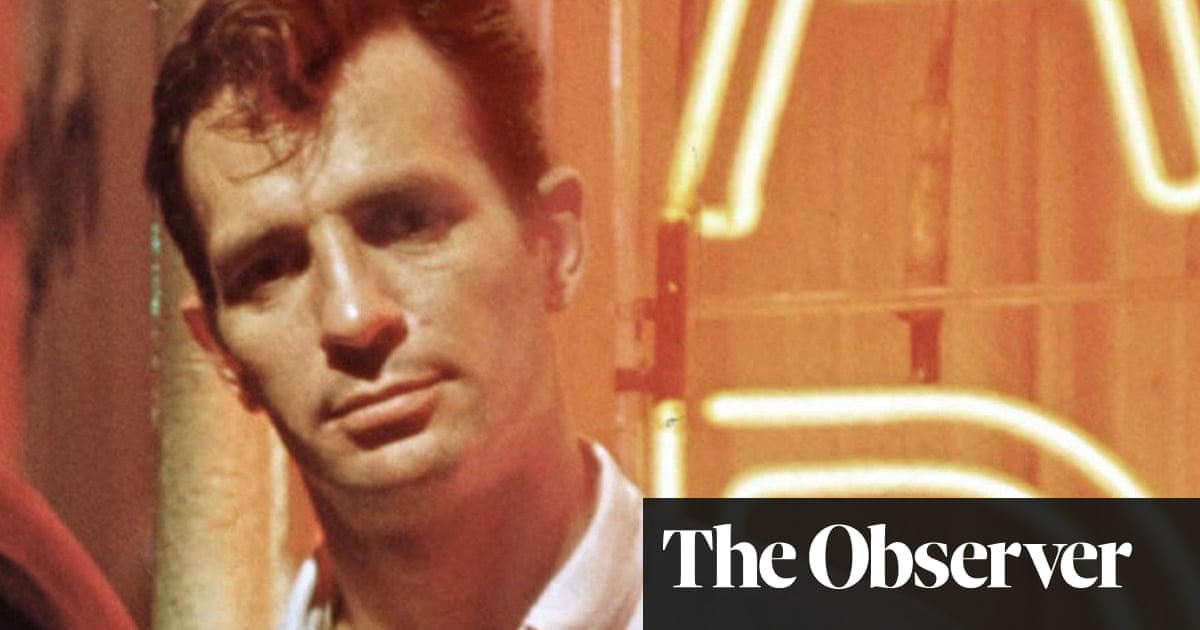

Show caption Author Jack Kerouac, photographed in 1958, was born 100 years ago. Photograph: Jerry Yulsman/Associated Press Jack Kerouac Jack Kerouac: still roadworthy after 100 years The author of On the Road had a messy, contradictory life. Yet he’s as relevant as ever – and not just for obsessed young men David Barnett @davidmbarnett Sun 13 Mar 2022 07.45 GMT Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

In July 1995, when I was 25 years old and working as a reporter on a local newspaper in the north of England, I made my first trip to America, by inveigling my way on to a junket for business journalists to Boston. On the last day of the trip, I jettisoned the itinerary and set out before dawn for the small town of Lowell, 30 miles away.

Lowell is the town in Massachusetts where writer Jack Kerouac is buried and where, a century ago this weekend, he was born. I’d discovered Kerouac about four years earlier, when I read On the Road, during a long coach journey to the bull-running festival of St Fermín in Pamplona, Spain, and then hoovered up his dozen or more roman à clef novels and books of poetry and dream, anything I could get my hands on. I was a fan.

I felt some kind of kinship with Kerouac I couldn’t explain. Maybe the working-class roots, the auto-didactic magpie-like gathering of knowledge. He had aspirations to be a journalist, writing articles for his university paper at Columbia. He dropped out of college after a year, following a football injury; I never went to university. He died, in 1969, 82 days before I was born. I took drugs on top of a mountain in the Lake District, echoing Kerouac’s summer as a fire-watcher on Desolation Peak, and wondered if I might be a reincarnation of him.

Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel On the Road is an American classic.

Kerouac seems equally revered and despised, for his jazz-infused spontaneous prose largely plotless novels, for his often contradictory lifestyle. In 1993, midway between me discovering On The Road aged 21 and going to visit Kerouac’s birthplace, Gap used him in an advertising campaign to sell their khaki trousers. The same year saw the BBC TV adaptation of Hanif Kureishi’s 1990 novel, The Buddha of Suburbia, in which social climber Eva chides protagonist Karim for reading Kerouac, quoting Truman Capote’s dismissive “that’s not writing, it’s typing”, and opining, “The cruellest thing you can do to Kerouac is re-read him at 38.”

Kerouac’s works often make it on to lists of red-flag books that, if you see on the shelf of a man you are dating, you should run a mile. The consensus seems to be that Kerouac is a thing for callow youths, to be grown out of, to be reassessed in maturity and found wanting.

And yet, here I am, more distance now between here and my visit to Kerouac’s grave than there was between me standing in the scorching July heat looking at the flat gravestone bearing his childhood nickname Ti Jean in Edson cemetery and Kerouac’s death in Florida. Here I am, arguing that Kerouac is more relevant than ever as we mark 100 years since his birth.

It’s Kerouac’s complex life, his contradictory views, his duality in so many things, that gives him more cachet than ever. Brought up a Catholic, he adopted a cherry-picked hybrid Buddhist spirituality, shot through with grief after the death of his older brother Gerard, aged just nine, who Kerouac revered as a saint.

He advocated freedom, abandonment of responsibility, heading out into the mystic night of a magical America where the land bulged on the horizon into infinity, yet he never cut the apron strings, eventually dying while living with his mother. Although ever the dutiful son, he was an absent father to his daughter Jan, even denying his paternity.

In his 20s Kerouac devoured Das Kapital and read the Daily Worker, and poet Allen Ginsberg said he was “overtly communistic”. By the end of his life he was supporting the Vietnam war and when his former road-buddy Neal Cassady, now riding with Ken Kesey’s acid-imbibing Merry Pranksters, visited him, Kerouac sombrely took the American flag one of the hippies was wearing as a cape and reverently folded it up.

Kerouac was married three times, and his portrayal of women in his works is derisory at best, reducing them to cardboard cutouts to facilitate sex or express maternalism. Yet he is widely thought to have had same-sex liaisons, and repressed his feelings for men all his life.

Jack Kerouac is a hot mess, in other words. And, really, aren’t we all? Does anyone know who or what they’re meant to be in the modern world? Gender is increasingly fluid, identity is a shifting concept, labels are meaningless.

Never mind selling khakis, it’s time, a century after his birth, that we made Kerouac a poster boy for the gloriously mixed-up, indefinable, shifting-sand landscape of 2022.