Why is the Solomon Islands-China security pact causing alarm?

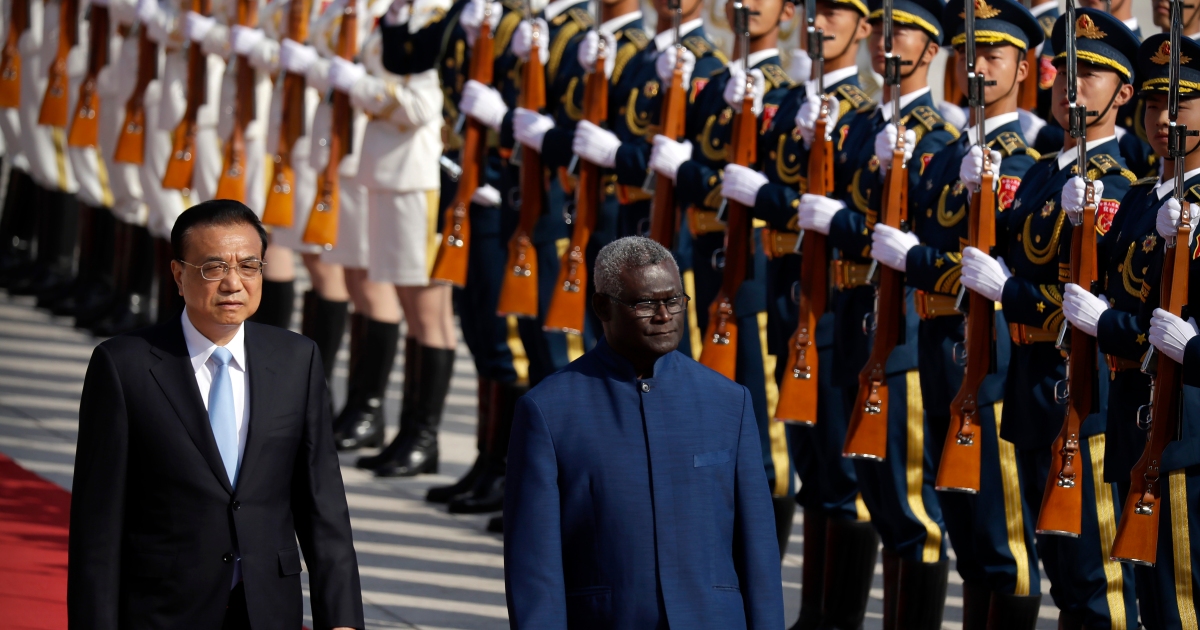

The Solomon Islands prime minister has been defending the just-signed pact to the country’s parliament amid concern from Canberra to Washington.

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare has been defending the security pact his government signed with China on Tuesday.

Sogavare told parliament the agreement with Beijing was necessary to deal with the Solomon Islands’s “internal security situation”.

The Pacific island nation has long struggled with political unrest, most recently in November 2021 when protesters targeted Honiara’s Chinatown and tried to storm Sogavare’s residence.

A contingent of Australian police helped restore stability following a request from the government. Australia had also led a 2003 multilateral mission following violence and a coup at the end of the 1990s.

Canberra raised alarm about the China pact when the draft was leaked online in March, and was trying to encourage Sogavare to rethink the plan. The United States and New Zealand have also expressed concern amid worries it could lead to China setting up a military outpost in the Pacific.

Mark Harrison, a senior lecturer in Chinese studies at the University of Tasmania, told Al Jazeera the deal was a “disaster” for Australia whose relationship with Beijing has long been strained.

“It is another difficult step for Australia in reassessing its future in a China dominated region,” Harrison said. “Australia completely misjudged the implications of China’s rise in the early 2010s, and the reassessment has been slow and equivocal, and still has a long way to go.”

What is the security situation in the Solomon Islands?

The Solomon Islands, with a population of less than 700,000, is a chain of hundreds of islands lying east of Papua New Guinea in the Pacific Ocean.

The capital, Honiara, is on the island of Guadalcanal, the site of a ferocious – and hugely significant – battle between US and Japanese troops in World War Two.

The one-time British colony has struggled with unrest since the late 1990s when ethnic tension erupted into violence and a coup brought Sogavare to power for the first time in 2000.

With the country in a state of near political and economic collapse, Australia and New Zealand deployed troops, stability was restored and a peace accord signed.

The calm did not last.

In 2003, after the government requested assistance from the Pacific Islands Forum, the region’s main diplomatic grouping, a multinational Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) was established with Australia leading the deployment.

RAMSI remained in the country for nearly 14 years, despite attempts by Sogavare to expel the mission whenever he was in power.

Sogavare was elected prime minister again in 2019 and months later moved to cut the Solomon Islands longstanding diplomatic ties with Taiwan in favour of Beijing.

The move was not popular with everyone in the Solomon Islands and Daniel Suidani, the premier of Malaita province, rejected the switch, saying he would push for independence for Malaita, the country’s largest province.

The riots in November also reflected the continued fallout from the decision to switch diplomatic ties.

Sogavare was not going to budge. He is invested in China & China invested in him. Does this bring Sols citizens under yoke of People’sLiberationArmy – Communist Party’s armed wing? While Sols sovereignty is respected, this has regional implications. What’s next in China’s sights? https://t.co/fuVNNejRT9 — Dr Shailendra B Singh (@ShailendraBSing) April 20, 2022

What is in the pact?

A text of the pact has not been released.

The leaked draft suggested it would allow Chinese warships to stop in the Solomons, and Chinese police to be deployed at the archipelago’s request to maintain “social order”. Neither party would be allowed to disclose the missions publicly without the written consent of the other.

“We intend to beef up and strengthen our police capability to deal with any future instability by properly equipping the police to take full responsibility of the country’s security responsibilities, in the hope we will never be required to invoke any of our bilateral security arrangements,” Sogavare explained to parliament on Wednesday, saying the pact complied with international and domestic law.

Sogavare has previously said that the Solomons has “no intention whatsoever … to ask China to build a military base” and on Wednesday stressed the deal was “guided by our national interests”.

Opposition leader Matthew Wale was sceptical.

“All the drivers of instability, insecurity and even threats to national unity in Solomon Islands are entirely internal,” the Solomon Star newspaper quoted Wale as saying on Wednesday. “This means that the deal, in giving opportunity to military posturing by China, has nothing to do with Solomon Islands national security. I doubt that the provision for this in the deal is inadvertent, rather it is calculated for geopolitical effect. On the part of Prime Minister Sogavare this is mercenary, on the part of China it is an opportunity too good to miss.”

Asked by Wale whether he would release the text of the agreement, Sogavare said he would talk to China.

What are the concerns of other countries?

Australia, which has had a security agreement with Honiara since 2017, has been the most vocal critic of the agreement, but countries elsewhere in the Pacific, including the US and New Zealand, have also voiced concern.

Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who is in the midst of a general election campaign, said on Wednesday the signing of the pact indicated the “intense pressure” from China felt by Pacific island nations.

Foreign Minister Marise Payne, in a joint statement with Zed Seselja, Minister for International, Development and the Pacific, said while Australia respected the Honiara’s “right to make sovereign decisions” it was “deeply disappointed” with the China pact.

“We are concerned about the lack of transparency with which this agreement has been developed, noting its potential to undermine stability in our region,” the statement said, saying Canberra was seeking “further clarity” on the terms of the agreement, and its consequences for the region.

The opposition Labor Party, which hopes to unseat Morrison’s coalition, described it as the “worst failure of Australian foreign policy in the Pacific since the end of World War II”. Shadow Foreign Minister Penny Wong noted that Australia had ignored warnings from Wale as early as August last year about the potential security pact.

In a statement on Wednesday, officials from Australia, the US, New Zealand and Japan expressed “shared concerns about the security framework and its serious risks to a free and open Indo-Pacific”.

For the record, I’m worried about China’s increasingly visible presence in the Pacific. But Australia needs to fundamentally re-imagine how we understand and engage with Pacific states and peoples to address it: https://t.co/nNKO3lnM2b — Joanne Wallis (@JoanneEWallis) April 20, 2022

The official announcement of the pact comes as Kurt Campbell, the US’s National Security Council Indo-Pacific coordinator, and Daniel Kritenbrink, its assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, embark on an official visit to the Solomons, Fiji and Papua New Guinea.

The US has already announced it plans to reopen its embassy in Honiara, which has been closed since 1993.

What about China?

In announcing the security deal, Beijing framed the pact as “normal exchange and cooperation between two sovereign and independent countries”.

Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin said Western powers were “deliberately exaggerating tensions” over the agreement.

Qinduo Xu, a political analyst the China-based public policy think tank Pangoal Institution, told Al Jazeera that he did not see “any reason” for Beijing to want a military base in the region to avoid further confrontation with the US and Australia.

He said the deal, instead, reflected China’s desire to ensure a stable investment environment in the Solomon Islands after Chinese shops and businesses were targeted by rioters last year.

It also solidifies Beijing’s new ties with the Solomon Islands in a region that is home to some of Taiwan’s last few diplomatic allies, he added.

“I think China wants to strengthen its position and its presence in this region because there are still other countries that recognise Taiwan instead of the mainland,” Xu said.

China claims Taiwan as its own and in recent years has stepped up efforts to woo the few countries that maintain ties with the self-ruled island. The Solomons was the sixth to switch since 2016.

China’s state media has cast Beijing as a benign power in the Pacific, suggesting it is the US that wants to build its military might in the region.

“The Solomon Islands should realize it is under the special attention of Washington because the US wants to use it as a pawn to contain China,” the tabloid Global Times wrote in an op-ed on Wednesday.