China at 73

China is observing National Day Oct. 1-7, celebrating the 73rd anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. Official events marking the country’s founding are scheduled around Tiananmen Square and other prominent sites in Beijing. According to reports, the authorities will probably increase security in the capital ahead of the event.

Increased security measures are almost certain nationwide, especially near monuments, politically sensitive landmarks, and transport hubs, during the holiday period. Some protests cannot be ruled out in large cities, particularly outside government installations in provincial capitals. Demonstrations are possible also in Hong Kong. However, police are planning to deploy heavily in the territory and will most likely quickly disperse any protests that occur.

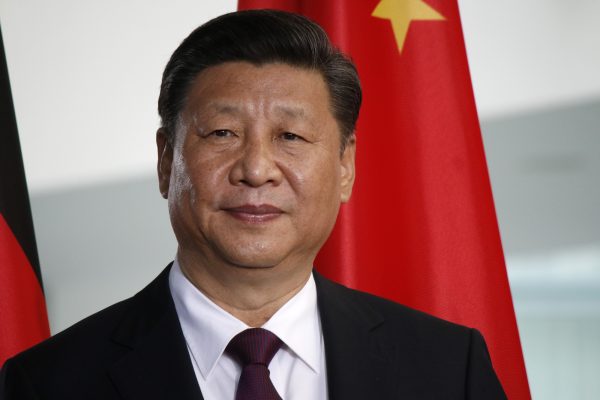

Meanwhile, the Chinese President Xi Jinping visited an exhibition in Beijing on September 27, according to the Chines state television. It was his first public appearance since returning to China from an official trip to Central Asia in mid-September, and dispelled unverified rumours that he had been under house arrest. Xi had been away from the public eye since his return from a summit in Uzbekistan, provoking unsubstantiated speculations of military coups in Beijing.

Xi has steadily consolidated power, reducing space for dissent and opposition since becoming party general secretary a decade ago. China has also become much more assertive on the global stage as an alternative leader to the US-led, post-World War II order.

In advance of the once-in-five-years Chinese Communist party’s (CCP) meeting, on September 16, former vice minister of public security Sun Lijun, former justice minister Fu Zhenghua, and former police chiefs of Shanghai, Chongqing and Shanxi were detained on corruption charges. The detentions amounted to China’s biggest political purge in years. Analysts believe that the purge will help Xi consolidate his authority over the party before he secures his third term during the forthcoming CCP meeting.

Xi has also faced serious human rights criticism from the international community for harsh policies in the north-western Xinjiang region. An estimated one million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities were reportedly detained in a sweeping crackdown ostensibly targeting “terrorism”.

Residents of a city in China’s far western Xinjiang region have run out of food after more than 40 days under a strict Coronavirus lockdown, according to a recent report published on Al Jazeera in September. The lockdown in Ghulja has also prompted accusations that it is targeted chiefly at Muslim Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic group native to Xinjiang. China has been accused of running a network of detention centres and prisons in the region. The United Nations observed that China has forcefully kept some one million Uighurs and other largely Muslim minorities in a system which may constitute crimes against humanity. The allegedly oppressive lockdown at Ghulja is part of China’s firm commitment to a policy of ‘ZERO COVID’. However, it is useful to weigh the effectiveness of these restrictions against the increasing hardships for the average citizen. These lockdowns may keep localized outbreaks from spreading but impose a great deal of economic and psychological inconvenience to the population.

Earlier this month, a long-awaited UN report looking into allegations of abuse in Xinjiang province accused China of “serious human rights violations”. China had urged the UN not to release the report, calling it a “farce” arranged by Western powers. But investigators said they found “credible evidence” of torture possibly amounting to “crimes against humanity”.

The report, formally called the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Right (OHCHR) Assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, and released on August 31, observed that ‘serious human rights violations have been committed in XUAR in the context of the Government’s application of counter-terrorism and counter-“extremism” strategies’ and that these violations flowed from ‘a domestic “anti-terrorism law system” that is deeply problematic from the perspective of international human rights norms and standards’.

Meanwhile, the International community has serious concerns on China’s designs. Riding on the wings of its dazzling economic growth, the PRC has advanced not only the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, but also a series of military ones: the modernization of the nuclear arsenal, the rollout of new stealth, cyber and artificial intelligence warfare technologies, the construction of the world’s second-largest blue-water navy, and the building of new overseas bases. And all this comes on top of a renewed territorial feud with India, “hostage diplomacy” against Canada, retaliatory economic pressure on Norway, South Korea, Australia and the Philippines, muscle flexing at Taiwan, aggressive maritime “land reclamation” in the South China Sea, naked attempts to manipulate public opinion abroad through social media and “wolf warrior diplomacy,” and the effort to exercise ever-greater control over international organizations, old and new alike.

China’s economic and political clout has grown so quickly that many countries, even those with relatively strong state and civil society institutions, have struggled to cope with the fallout. An analysis carried out by the Carnegie Endowment in 2021 studied Chinese activities in four South Asian states—Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka that shape or constrain the choices and options for local political and economic elites, influence or constrain the parameters of local media and public opinion and China’s impact on local civil society and academia. The study found that China’s tools of influence are varied and modified depending on the extent of its engagement in a country, on the resilience of that country’s institutions, and China’s personal relationships with key regime actors. These may be in the form of incentives or threats, used to deter or compel both state and non-state actor or coercive threats used to lead local actors such as journalists to self-censor.

Meanwhile, China continues to pursue authoritarian diplomacy in Asia. On August 10, China announced that it will start a feasibility study for an ambitious Tibet-Nepal Railway project. The proposed 170-kilometre railway, part of the Belt and Road Initiative, will link Kerung in southern Tibet to Nepal’s capital Kathmandu, entering Nepal in Rasuwa district. The plan is to eventually extend the railway to India. The Third Pole reported that building the railway from Kerung to Kathmandu would cost about 38 billion yuan ($5.5 billion), almost equal to total government revenues for the country in 2018.

Earlier in February, the BBC reported that a leaked Nepalese government report accused China of encroaching into Nepal along the two countries’ shared border. Their common border, laid out in a series of treaties signed between the two countries in the early 1960s, runs for nearly 1,400km (870 miles) along the Himalayan Mountains. Surveillance activities by Chinese security forces had reportedly restricted religious activities on the Nepalese side of the border in a place called Lalungjong. The area has traditionally attracted pilgrims because of its proximity to Mount Kailash, which is a sacred site for both Hindus and Buddhists. The report also concluded that China had been limiting grazing by Nepalese farmers. In the same area, China was reportedly building a fence around a border pillar, and attempting to construct a canal and a road on the Nepalese side of the border.

China’s strategy in Sri Lanka is probably far more aggressive and dictatorial, albeit in a different sense. The 2005 election of President Mahinda Rajapaksa fundamentally transformed the Sino-Sri Lankan relationship. Rajapaksa upgraded their ties to a “strategic cooperative partnership,” and enthusiastically supported China’s Belt and Road initiative. The ports of Sri Lanka, positioned as the island-nation is along the principal east-west sea lines of communication (SLOCs) connecting China to its energy suppliers in the Middle East and Africa, were the real prize for China, however. Since 2016, analysts have raised concerns over the implications of China’s massive infrastructure ventures and investments in the Sri Lanka including ports of Colombo and Hambantota that turned into white elephants — which was effectively ceded to Chinese control half a decade ago after Sri Lankan authorities recognized they could no longer pay off the loans. It had not only forced Sri Lanka into debt trap and deficient enough to head for bankruptcy, but posed permanent security threats and defense consequences of Beijing’s use of economic statecraft.

Some analysts apprehend the multi-billion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) could be the Trojan horse of China’s economic global penetration through a system of “debt-traps”. A 2018 report by the Center for Global Development (CDG) of the Harvard Kennedy School examines what the authors define as “debt diplomacy” – the practice of lending millions of dollars to countries that cannot afford to pay back, using the debt as a leverage on assets and sovereignty – and identifies eight potential target-countries of debt insolvency, including Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Lack of hard data makes it difficult to prove China’s claim that it outranks the world’s other major economies by the amount of debt it has deferred collecting from developing countries, economists said. Chinese loans have supported infrastructure projects across Africa and Southeast Asia, even as recent loan issues in Laos and Sri Lanka have added suspicion about Chinese debt. Around half of Loas’ total debt is owed to China, on loans for various projects, including the China-Laos railway. China declined to join the Paris Club, a decades-old group of officials from 22 countries who help nations pay off loans, reportedly because membership would require more transparency.

Serious questions are raised also about China’s trade practices. Foreign business entities particularly western have been raising the issue of IP theft leading to the loss of billions over the years. The US Congress tried to introduce a bill called “US Innovation and Competition Act (USICA)” In the summer of 2021. The discussion around this bill in the Senate, saw concerns such as demands for the bill to include special “research security” provisions to stop China’s clandestine designs of acquiring technological knowhow from the US giants. Estimates by the US trade representative pegged the Chinese theft of American IP cost the US firms between $225 and $600 billion each year, that too four years ago.

Even more alarming is what China does with the stolen IPs. It is alleged that China converts them into military capabilities. Once the knowhow is acquired from foreign entities, dozens of top Chinese universities are mobilized for formally converting it into local patents. The Government later distributes these patents among various local companies for commercial exploitation.

Then there is state sponsored hacking. A report in May 2022 exposed a yearlong malicious cyber operation spearheaded by the notorious Chinese state actor, APT 41. The attack had siphoned off estimated trillions of US Dollars in intellectual property theft from approximately 30 multinational companies within the manufacturing, energy and pharmaceutical sectors. Cybereason, a Bostion based cybersecurity firm unearthed a malicious campaign — dubbed Operation CuckooBees — exfiltrating hundreds of gigabytes of intellectual property and sensitive data, including blueprints, diagrams, formulas, and manufacturing-related proprietary data from multiple intrusions, spanning technology and manufacturing companies in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Another aspect of China’s aggressive strategies is the surge in AI based surveillance over its citizens. Dozens of Chinese firms have built software that uses artificial intelligence to sort data collected on residents, amid high demand from authorities seeking to upgrade their surveillance tools, according to a Reuters review based of government documents. According to more than 50 publicly available documents examined by Reuters, dozens of entities in China have over the past four years bought such software, known as “one person, one file”. The technology improves on existing software, which simply collects data but leaves it to people to organise. Mareike Ohlberg, a Berlin-based senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund said that “One person, one file ” is a way of sorting information that makes it easier to track individuals”.

The documents Reuters analysed offered varying amounts of detail on how the software would be used. Some indicated that the software would be used with facial recognition technology that could, identify whether a passerby was Uyghur, connecting to early warning systems for the police and creating archives of Uighur faces. Yet others revealed that the software should be able to collect information from the individual’s social media accounts. Some documents considered the possibility that the software would be used to compile and analyse personal details such as relatives, social circles, vehicle records, marriage status, and shopping habits.

Meanwhile, in 2020, The US State Department designated the Confucius Institute U.S. Center (CIUS) as a “foreign mission” of the Chinese government, calling out the organization for its role as “an entity advancing Beijing’s global propaganda and malign influence campaign on U.S. campuses and K-12 classrooms.” Confucius Institutes are Chinese-language and cultural centers funded by grants from China — more than 1,000 have been established around the world, usually on university campuses. Other argue that these programs omit issues the Chinese Communist Party considers to be politically sensitive, such as political freedoms in Tibet and Xinjiang or the 1989 crackdown on protesters in Tiananmen Square. There are charges that Confucius Institutes avoid teaching about political content altogether. Critics have also worried about the constraints that Confucius Institutes impose on academic freedom. In 2009, North Carolina State University disinvited the Dalai Lama after its Confucius Institute objected to inviting the Tibetan spiritual leader in exile. Germany’s Education Ministry in 2021 called on the country’s universities to end co-operation with the Confucius Institute (CI). In June 2021, Finland terminated a cooperation contract between Helsinki University and the Confucius Institute following accusations of spreading Chinese soft power, conducting espionage, and an attempt to block discussions on Tibet. In July, 2022, Rishi Sunak, the Prime Minster aspirant in the United Kingdom, had promised that if he were elected, he would shut down all thirty Confucius Institutes in England.

Embolden by the pandemic, the China’s authoritarian model presents new and challenging set of risk to the current international system. The world has been realizing bolstering despotic regime of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since the beginning of the 21st Century. The CCP is busy in repression of dissidents, mass arbitrary detention, forced labor, high technology surveillance and worst human rights abuses at the domestic level, muscle flexing at neighbors, and economic coercion, techno-authoritarianism, IP theft, disinformation and overt propaganda, instrumentalize the Chinese diaspora to further Beijing’s political interest, encourage complicit and corrupt power elites, social unrest and debt trap at the behest of vested interests, threats to security and sovereignty, lack of transparency and accountability at the global level.