How to counter China, the U.S. courted the Philippines

America has rushed to mend relations with its former colony after ties frayed under former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. It has lavished attention on new leader Ferdinand Marcos Jr and sent military equipment and vaccines. Washington needs Manila in its camp as tensions with China rise in the Indo-Pacific. Reuters got inside the charm offensive.

Shortly after winning the presidency of the Philippines in May of last year, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr took his first congratulatory call from a foreign head of state.

U.S. President Joe Biden was on the line.

Biden’s speed in wishing the new president well delighted Marcos, according to brother-in-law Gregorio Maria Araneta III, who said the Philippine leader proudly told his family about that call a few days later over lunch. It “put a smile on his face,” Araneta, one of the country’s most prominent tycoons, told Reuters in a rare interview, speaking from his wood-paneled office in Manila.

The U.S embassy in Manila confirmed Biden was the first to call. What followed was two trips to the United States in less than a year for Marcos, and visits to the Philippines by high-ranking Biden administration officials. Among them: Vice President Kamala Harris, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin.

Manila-based political analyst Julio Amador III described the U.S. outreach as “unprecedented love-bombing” aimed at resetting the U.S.-Philippines relationship. Marcos’ predecessor, the populist firebrand Rodrigo Duterte, was openly hostile to the United States and attempted to bring his country closer to communist China during his six-year term.

There is urgency to the U.S. charm offensive: America needs Manila squarely in its camp as tensions with China rise in the Asia-Pacific.

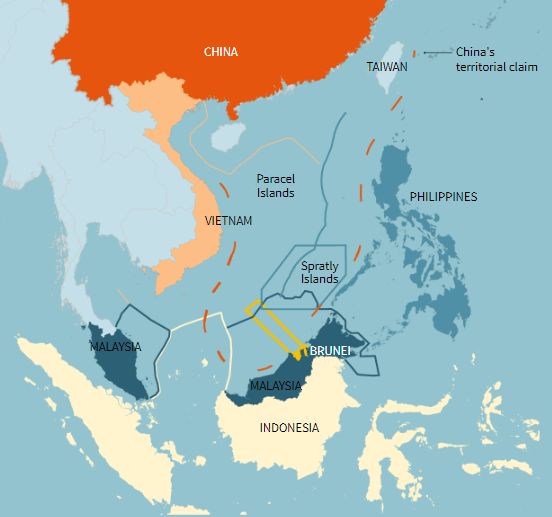

The Philippines, Taiwan’s neighbor to the south, would be an indispensable staging point for the U.S. military to aid Taipei in the event of a Chinese attack, military analysts say. China’s ruling Communist Party views democratically governed Taiwan as an inalienable part of China and refuses to rule out force to bring the island under its control.

Under President Xi Jinping, Beijing has laid claim to an ever-widening swathe of the South China Sea and is bent on making his nation the unquestioned military power in East Asia. Such a shift would have far-reaching consequences for U.S. influence, regional security and global trade. More than a fifth of the world’s shipping passes through the South China Sea annually. The narrow straits around the Philippines and Taiwan bristle with undersea internet cables and are vital channels for U.S. naval forces patrolling the region.

Reuters has been detailing the race between China and the United States to bulk up on advanced technologies that could determine who secures military and economic supremacy this century. Aerial and sea drones, AI-controlled weapons and cutting-edge surveillance are fast reshaping warfare, with implications for the global balance of power.

For the United States, cementing alliances in the Asia-Pacific region is likewise crucial to keeping China in check. The U.S. embrace of Marcos is key to that project.

To get inside the American effort at mending ties and Marcos’ decisive pivot to Washington, Reuters spoke to more than two dozen current and former officials from both countries. Some spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media.

The reporting revealed a picture of a superpower anxious about China, knocked off stride by Duterte, and eager to partner with Marcos despite his family’s history of brutality and corruption.

“Turn to the United States and tell them to produce.”

Marcos’ father, the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos Sr, was a steadfast U.S. ally who was deposed in 1986 after Filipinos revolted against his regime. The elder Marcos was accused of orchestrating the detention and killing of thousands of political enemies and illegally siphoning billions of dollars from public coffers. He died in exile in Hawaii in 1989 without facing trial. After his death, family members returned to the Philippines, where they have remained a force in politics.

President Marcos did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this report. He has sought to recast his father’s time in power as a golden era of development for the Philippines, while saying little about the allegations of wrongdoing. “Judge me not by my ancestors, but by my actions,” he said after his 2022 election win.

The U.S. State Department declined to comment on the Marcos family’s past. In a statement to Reuters, it said U.S support for civilian security, democracy and human rights was “integral to U.S. foreign policy and national security interests” in the Pacific. “The U.S-Philippines alliance is strategically irreplaceable, and a Philippine government that respects the rule of law, good governance, and human rights is essential to maintaining a strong alliance.”

Reuters also learned of efforts by senior Filipino military and government officials that successfully stalled moves by Duterte to shred the U.S.-Philippines security alliance. The reporting also sheds light on Marcos’ calculus about the risks of aligning himself too closely with China.

Duterte’s pro-Beijing stance was unpopular with the Filipino public, failed to produce as much Chinese investment as he had promised, and didn’t stop territorial disputes between the two nations, which have intensified.

In October, the Philippines alleged that a Chinese coast guard vessel and a maritime militia boat “intentionally” collided with two Filipino boats on a journey to resupply Philippine personnel stationed at Second Thomas Shoal, a contested outpost in the South China Sea. China claimed that the Filipino vessels were at fault.

The United States swiftly backed the Philippines, warning Beijing that it would defend its ally in the event of an armed attack under a 1951 mutual defense treaty.

It’s a stance that pleased Manila, which has felt at times that Washington hasn’t done enough to support the Philippines in such confrontations, two current and one former official told Reuters.

Duterte declined to comment for this report.

China’s Foreign Ministry, in a statement to Reuters, characterized China and the Philippines as “close neighbors across the sea” with a common interest in friendship. It noted that China was the Philippines’ largest trading partner and a major source of investment that “had improved the living standard of the Filipino people.”

Without naming the United States, the Foreign Ministry added that “some countries, out of self-interest and with a zero-sum mentality, continue to strengthen their military deployment in the region, which is precisely aggravating tensions.”

Regarding Taiwan, the statement said China “insists on striving for the prospect of peaceful reunification with the utmost sincerity and effort, but will never commit itself to renouncing the use of force.”

The Philippines is a former American colony that was granted independence in 1946, shortly after World War II. As part of the so-called first island chain ─ a string of islands that encloses China’s coastal waters ─ it has long been a key node in U.S. defense strategy in the Pacific.

In addition to the Philippines, the United States for decades has partnered with other regional allies, including Japan, South Korea and Australia, to access military bases and conduct naval exercises. The enduring U.S. presence has rankled an increasingly militarized and confident China.

The People’s Liberation Army now has a sophisticated missile force designed to destroy the installations, aircraft carriers and warships that are the backbone of American power in Asia. China boasts the world’s biggest navy. It has stepped up “grayzone” operations at sea – aggressive military actions that fall short of acts of war – especially around Taiwan and in contested waters of the South China Sea.

War games staged last year by think tanks, including the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), based in Washington, illustrated how indispensable the Philippines would be for a U.S defense of Taiwan.

U.S. access to Philippine runways and aircraft fuel proved vital in scenarios showing a successful repulsion of Chinese forces in the early days of a conflict, said Becca Wasser, a defense analyst and wargaming expert who ran the exercises for CNAS and has done the same for the U.S. Department of Defense.

“I think that crystallized how important the Philippines could be and how, in some ways, relying on Japan and Australia, which are farther away, is just not enough,” said Wasser, who leads The Gaming Lab at CNAS.

But the U.S.-Philippines relationship was strained with the 2016 election of Duterte, nicknamed “The Punisher” in the media. He quickly launched an anti-narcotics crackdown that resulted in extrajudicial killings of thousands of suspected criminals, a policy that raised alarms in the administration of President Barack Obama. Duterte also set about moving his country closer to economic powerhouse China, whose leader Xi shares his criticism of a U.S.-led world order.

In October 2016, Duterte traveled to Beijing and proclaimed a new era of Sino-Filipino cooperation. “America has lost,” he told an audience of Chinese business executives. “I’ve realigned myself in your ideological flow.” Duterte returned to Manila with $24 billion in commitments under the Belt and Road Initiative, a global investment project that Beijing has used to wield soft power. Only a tiny fraction went ahead, according to the Philippines National Economic Development Authority.

Hostilities peaked in early 2020 after the United States canceled the visa of Senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa, who had spearheaded Duterte’s drug war in his previous post as head of the Philippine National Police. On Duterte’s orders, the Philippines notified Washington of its intent to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) within 180 days. Ratified in 1999, the pact sets rules for rotating thousands of U.S. troops into and out of the Philippines. The VFA is key to implementing the bedrock Mutual Defense Treaty of 1951 that requires the United States and the Philippines to support one another in the event either is attacked in the Pacific.

Dela Rosa did not respond to a request for comment. At the time, he said the cancellation of his visa was the latest in a list of “gripes and disrespect” by the United States.

A retired senior Filipino military officer who served during that time recalled that U.S. officials were “very worried, they thought everything will be like a house of cards falling.”

The Americans “saw the increasing influence of the Chinese” over Duterte, the officer said.

But behind the scenes, the Philippine military establishment was pushing back against Duterte’s efforts to chip away at the U.S. alliance, the Filipino military official and six others told Reuters.

U.S.-Philippines cultural ties are strong. More than four million Filipino-Americans live in the United States, and public opinion surveys have consistently shown that Filipinos have high levels of trust in America compared to China. Duterte at a 2017 press conference said “our soldiers are pro-American, that I cannot deny.”

Two of the military officials said the president early in his term had ordered the Philippine navy to stop patrols in areas of dispute with China, instructions they said were ignored by senior commanders on the grounds of national defense. Philippine navy chief Vice Admiral Toribio Adaci Jr did not respond to a request for comment.

In late 2018, China and 10 Southeast Asian nations convened their first joint maritime drills. Some were held off the coast of China’s southern Guangdong province. While other countries showed up with frigates and destroyers, the Philippine navy sent a single logistics support vessel, according to a senior Filipino military officer with knowledge of the previously unreported events.

The official explanation given to China was that the Philippine navy couldn’t free up larger vessels because it hadn’t received enough advance notice of the exercises, the officer said. The real reason, the officer said, was to avoid looking like a military ally of China: “If we sent a warship, it would not send a good message to the international community.” Two other Philippine officials with knowledge of the situation confirmed this account to Reuters.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to a request for comment on the incident.

Meanwhile, the Philippine military continued joint exercises with the United States, despite a public pronouncement by Duterte in September 2016 that such drills would end because they were something “China does not want.”

A senior defense official, who asked not to be named, told Reuters that he pushed back on that edict and stressed to Duterte the benefits of the transfer of U.S. technologies. The exercises continued.

Still, to avoid Duterte’s ire, the two forces ceased mock combat drills, focusing instead on disaster response, according to Blake Herzinger, a former maritime security advisor to the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

“We had to rename all the exercises,” said Herzinger, who was a U.S. government contractor working on U.S.-Philippines maritime security cooperation at that time. For example, long-running regional warfare exercises known as CARAT, or Exercise Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training, were ended and reinstated with the Filipino name “Sama Sama” meaning “together.”

The navy also managed to scuttle plans by a Chinese-Philippine joint venture, Fong Zhi Enterprise Corporation, to transform Fuga Island in the northern Philippines into a “smart city” with a high-tech industrial park. The remote island is located less than 400 kilometers from Taiwan and close to subsea internet cables connecting the Philippines with the rest of Asia. Duterte agreed in principle to the $2 billion deal during a 2019 trip to Beijing. But he quickly backtracked after Philippine military officials went public with fears that China might use the development as cover for a spy post or to facilitate an invasion of Taiwan.

Fong Zhi Enterprise Corporation could not be reached for comment. A representative of the Chinese investor, Hongji Yongye, declined to comment.

Senior government officials in 2019 killed efforts by Chinese companies to take over a shipyard in Subic Bay, a former U.S. naval base in the Philippines that closed in 1992 after Manila terminated a bases agreement with Washington.

Two Chinese firms expressed interest, the government said at the time without naming the companies. Teodoro “Teddy” Locsin Jr, then-foreign minister of the Philippines, told Reuters he concluded the United States would consider such a sale to be “an act of hostility,” given the strategic value of the site. The deepwater port is in close proximity to both the Bashi Channel facing Taiwan and the South China Sea. Reuters was unable to determine the name of the Chinese companies.

Jose Manuel “Babe” Romualdez, the Philippine ambassador to the United States, said he hustled to find an American buyer instead. In 2022, Cerberus Capital Management, a New York-based private equity firm that has invested in defense contractors and national security assets, paid $300 million for the shipyard.

Cerberus declined to comment on the deal.

China’s Foreign Ministry, in its statement, said the Fuga Island and Subic Bay projects were “purely the actions of enterprises of the two sides and should not be subject to excessive political interpretation.”

Charm offensive

While many Filipino officials were alarmed by Duterte’s efforts to cozy up to China, two officials told Reuters there was an upside: They began to hear a more respectful tone from their U.S. counterparts.

“The U.S. was, of course, nervous, and they showed this nervousness by actually reaching out to us and actually speaking in a language that’s very uncharacteristic of the United States,” one of the officials said.

A change of U.S. administrations with the election of U.S. President Donald Trump led to more concrete shows of support for the Philippines.

Many of the islands, shoals and reefs in the South China Sea now claimed by the Philippines – some of which are disputed by China and other nations – were not formally annexed by Manila until 1978. That was well after the signing of the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Philippines, creating ambiguity as to whether Washington would assist its ally if an attack came in those places. The United States removed any doubt in 2019, when then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo traveled to Manila to assure officials that the United States would defend the Philippines in those areas too.

Pompeo told Reuters he wanted to make it “unambiguously clear” that the United States was committed to providing the “deterrence support that was necessary to push back against an ever-increasing footprint of the Chinese Communist Party in the South China Sea and elsewhere.” It was the “singular purpose of the visit,” Pompeo said.

He also gifted drones for use by the Philippines to fight Islamist militants operating in the south of the country. The Obama administration had halted some weapons sales to the Philippines over human rights concerns.

When Trump came into office and stopped “talking about human rights, suddenly the major complicating factor in the relationship disappeared,” said Gregory Winger, a political science professor at the University of Cincinnati specialized in U.S.-Philippines relations.

Two Filipino officials agreed. Between Trump and Duterte there was “a mutual admiration club,” one said.

Duterte kept extending the deadline to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement or VFA. Advisors had warned him against the termination. Behind the scenes, military planning for its renewal continued.

In December 2020, shortly after Biden defeated Trump for the presidency, Duterte announced specific terms for keeping the VFA intact: 20 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine.

The Philippines, with a population of about 110 million people, had been hit hard by the pandemic and had few resources to fight it. Vaccine diplomacy would prove critical to keeping the VFA alive, according to a senior Filipino official with direct knowledge of the situation.