China’s Poverty Alleviation has failed

China has always had an urban-rural divide and despite Xi Jinping’s ambitious plans to remove people from poverty, recent evidence indicates increasing destitution in rural areas of China. A clear sign of policy failure. For instance, in Zhongwei, a city in northwest China’s Ningxia Hui autonomous region, fighting poverty seems to be a never-ending battle. In July, the city’s Shapotou district announced that 28 more individuals had been added to a poverty relapse watch list. According to Xinhua, China has spent nearly 1.6 trillion yuan (US$ 306 billion) to alleviate poverty since Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012. In 2021, Xi grandly declared that absolute poverty had been eradicated. The next milestone, he said, was to attain common prosperity and a decent standard of living for all by 2050. Those ambitions rest on preventing a large-scale re-emergence of poverty. This grand ambition is fading as more and more evidence is emerging of people relapsing into poverty across China.

China’s focus on poverty was outlined in the No. 1 Central Document, the first policy directive issued by the CPC in 2021 and then re-issued annually. There is no doubt that poverty or maintaining people’s livelihoods is an ongoing concern for CPC leaders. This was evident during the covid pandemic lockdown in 2022 when a large numbers of rural residents, mostly migrant workers, lost their jobs. The issue was raised again in January 2024, when the Central Rural Work Leading Group, said preventing a massive return to poverty was “both an economic and political task”.

In July 2024, the fight against poverty relapses again featured prominently when the CPC’s Central Committee gathered to map out the country’s economic and national development plans for the next decade. The CPC leadership called for constant surveillance of low-income individuals and regular monitoring, nationwide of rural populations, where poverty is more prevalent. The statistics tell their own story. Last October, the Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs claimed that construction of a “low-income population dynamic monitoring platform” had been “basically completed.” This was for coverage of more than 66 million low-income people, more than 3 million of whom were considered at risk of falling back into poverty. A perusal of the 2021 National Census shows that nearly 510 million people China’s rural regions, accounting for 36% of the country’s population were poor.

Pertinently, when Chinese Premier Li Qiang inspected the southern province of Guizhou in April 2024, he had warned party cadres that CPC would hold them responsible if people slipped back into poverty. He emphasised “We must firmly adhere to the bottom line of not allowing large-scale relapses into poverty by enforcing and consolidating the responsibilities of all parties, maintaining the intensity of support efforts, and ensuring that all policies are well coordinated and implemented”. So, there is a challenge before policy makers in China. Slipping back into poverty appears to be the norm rather than a exception. Officials who regularly update the list on families in dire financial straits, have a dual responsibility of ensuring that they do not fall below the poverty line while making sure that they do not become too dependent on government handouts.

The Shapotou district did not say how many people in total were on the list. Their updates are part of the efforts by the local administration to prevent a return to widespread poverty even as China’s economy struggles to regain momentum. The achievement of the goal to eliminate poverty is laudable as it would help build a more equitable society in China, but the focus on social stability and by extension stability of the CPC creates contradictions in implementation of the policy. There is little doubt that the anti-poverty movement has been defined as one of Xi’s great achievements. However, if absolute poverty returns it will be a big issue. More importantly, it would signal that China’s model of fighting poverty through massive investment “is not sustainable”.

While the overall picture is clear, variance in poverty lines across Chinese provinces is more complex. In Ningxia, for example, individuals who earn less than 9,000 yuan a year are considered to be living below the poverty line and are eligible for government assistance. This compares with 8,050 yuan in southwestern Yunnan province, and 7,800 yuan in the eastern province of Jiangxi. This has to do with local governments willingness and capacity to tackle poverty. So what parameters are used by the CPC to monitor poverty? Local governments monitor individuals who have risen above the poverty line but have unstable incomes. Monitoring is also done if the individuals hover above the line but face unexpected challenges like natural disasters or illness. Lower-level CPC cadres are finding themselves under immense pressure to keep poverty under check. As it is a political issue primarily, people whose names are added to the dossiers are and considered risks to the anti-poverty drive are subject to regular monitoring.

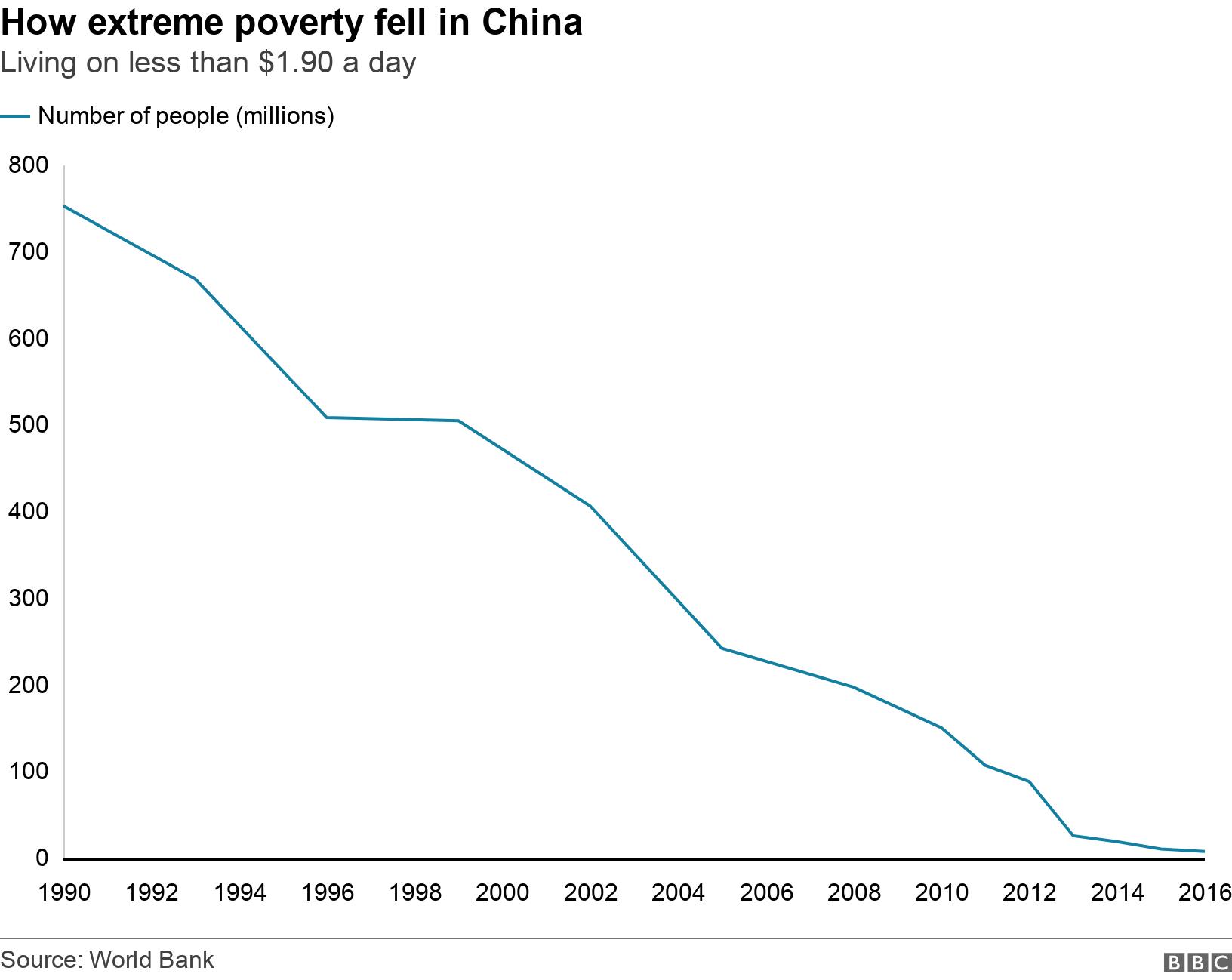

Recent evidence from several provinces shows that China’s poverty alleviation has failed, and the rural-urban divide continues to grow. Undoubtedly, China can be praised for lifting tens of millions out of absolute poverty in recent decades, but many analysts claim that its achievements have been overstated by some CPC cadres who exaggerate results to please Xi Jinping! Given the nature of the Chinese beast it is a plausible possibility. If this indeed be the case then other criticisms including fabrication of the poverty relapse dossiers, and over-reliance on government subsidies that make recipients more vulnerable once they stop getting government aid. China’s poverty is here to stay, whether Xi likes it or not.

Source: https://theaseanpost.com/article/learning-chinas-poverty-alleviation-program

Source: https://senecaesg.com/insights/poverty-alleviation-progress-in-china/