What’s the Difference Between Mainland China and Hong Kong?

When a citizen of mainland China travels to Hong Kong, they’ll need to have their passport, likely want to exchange their yuan for Hong Kong dollars, and be prepared to follow laws that are often significantly different from the mainland.

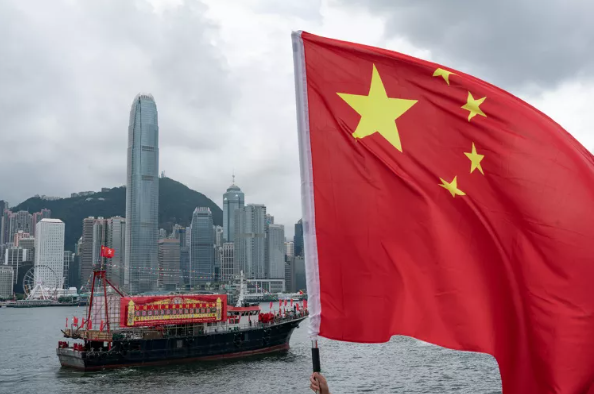

Hong Kong’s sophisticated financial system, housed in a skyline of gleaming skyscrapers, processes trillions in assets under a regulatory framework distinct from mainland China. As a special administrative region (SAR), Hong Kong maintains its own currency, runs its own stock exchange (one of the world’s largest), and operates with different tax laws—all under systems developed during 156 years of British rule that ended in 1997.

While Hong Kong’s gross domestic product (GDP) represents only about 2% of China’s total economy, its financial markets and international banking sector are outsized in the country’s global trade and investment flows. The territory annually has about $600 billion in bilateral trade with mainland China, highlighting its continued importance as a financial intermediary between China and global markets.

Hong Kong vs. Mainland China: An Overview

Hong Kong is one of Asia’s busiest cities. The SAR is an international financial hub, business center, and shopping and tourist destination. Nevertheless, it’s entirely under the sovereignty of China and, at times, has fiercely resisted Beijing’s interference in its political life.

2

Pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong would like the region to remain distinct from other Chinese cities. That makes the relationship between Hong Kong and mainland China complex. Having said that, mainland China and Hong Kong complement each other economically, even if there’s continued controversy around their political relationship.

The History of Hong Kong-China Relations

Hong Kong’s relationship with mainland China has involved complex political and economic interactions across centuries. The territory’s modern history began during the First Opium War, when Britain seized Hong Kong Island in 1841. The following year, China formally ceded it to Great Britain in the Treaty of Nanking. British control expanded with the addition of the Kowloon Peninsula in 1860 after the Second Opium War.

The British Colonial Era (1841-1997)

During British rule, Hong Kong developed into a major trading port and eventually a global financial center. The colony operated under British common law, developed Western-style financial institutions, and established international business practices that would later distinguish it from mainland China’s socialist system.

Britain negotiated a 99-year lease of its Hong Kong colony with China in 1898. That lease ended in 1997 when Britain returned Hong Kong to China. It then became the Hong Kong SAR of the People’s Republic of China.

The Transition (1984-1997)

In 1984, Britain and China signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration, setting the stage for Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty. The agreement introduced the concept of “one country, two systems,” promising that China’s socialist system would not be imposed on Hong Kong. Under this framework, Hong Kong would maintain its capitalist system and independent judiciary for at least 50 years after the 1997 handover.

4

Early SAR Years (1997-2014)

After becoming a special administrative region in 1997, Hong Kong maintained significant autonomy in most areas except foreign relations and defense. The territory preserved its separate legal system, currency, and financial regulations, helping it retain its status as a global financial hub.

The era wasn’t without its controversies between the region and the mainland. Security legislation in 2003—it would be shelved until 2024 when it was passed as Article 23—was pulled after massive protests on Hong Kong’s streets by hundreds of thousands.

Contested Sovereignty (2014-Present)

There are many reasons for the shift in relations between Hong Kong and the mainland in the last 15 years or so, but one is simply the balance of power has changed significantly. In 1997, when Britain handed Hong Kong back to China, the territory wielded extraordinary economic leverage. Despite having less than 1% of China’s population (6.5 million versus 1.2 billion), Hong Kong’s financial sector and international trade links generated an economy one-fifth the size of mainland China’s. This economic might gave Hong Kong significant influence in maintaining its autonomous systems.

However, the decades since have seen a dramatic reversal. While mainland China has seen explosive growth to become the world’s second-largest economy, Hong Kong’s growth has been modest, if not flat. By 2024, Hong Kong’s economic output represented less than 2% of China’s GDP—a striking decline from its previous position.

There are just a few differently administered areas of the world that, for historical and geopolitical reasons, aren’t sites of contestation over political rights and sovereignty. In the last decade or more, Chinese “interference” in Hong Kong governance has provoked strong reactions from democratic activists in the region:

2014: The “Umbrella Movement” involved widespread protests over proposed changes to Hong Kong’s electoral system.

2019: Large-scale protests erupted over a proposed extradition bill that would have allowed criminal suspects to be sent to mainland China.

2020: Beijing implemented a new national security law.

2021: Electoral system changes required candidates to be pre-approved by a government committee.

2024: Hong Kong’s legislature passed Article 23, a new security law expanding government powers.