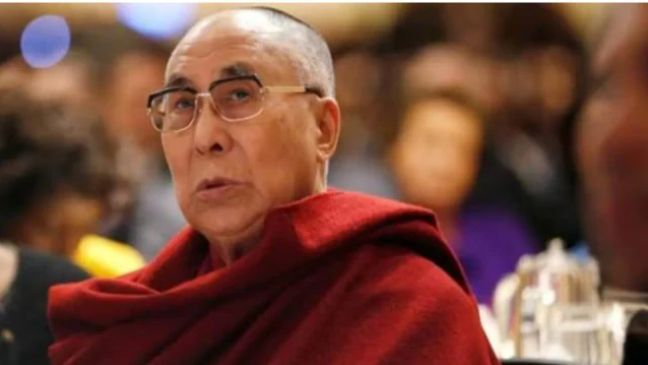

Conflicts surrounding the Dalai Lama’s rebirth: Can China dictate Tibet’s destiny?

China, it appears, is getting anxious about the Dalai Lama’s future. On February 10, China’s foreign ministry expressed hope that the Tibetan leader will “return to the right path”. While responding to the demise of the Dalai Lama’s brother Gyalo Thondup, Beijing stated that if certain preconditions are fulfilled, it would be amenable to discuss the Dalai Lama’s future. In 2023, Beijing had said discussions on his “personal future” or “whether he wants to return to China” were open if he gave up “independence” and acknowledged that Tibet and Taiwan are inseparable parts of China. Beijing ceased dialogue with the Dalai Lama’s envoy in 2010. It doesn’t recognise the Tibetan government-in-exile.

The Dalai Lama, meanwhile, has not taken a firm stand and has been making conflicting statements regarding his afterlife. In 2004, he stated that it is up to the Tibetan people to decide if they want the 15th Dalai Lama. About a decade later, he said the next Dalai Lama could be a woman, a “blonde woman” who must be attractive to be useful.

To pre-empt any interference from Beijing, the Dalai Lama had also said that only he would decide the place and mode of his reincarnation and that he would take a call, when he is “90” in July 2025. The Zurich-based Gaden Phodrang Trust would oversee the process, and he would leave a note specifying the location of the new birth. His forthcoming book, scheduled for release in March, is expected to offer a perspective on Tibet’s future.

However, in 2019, he had also discussed abolishing the reincarnation system due to its feudal roots and also because a “weak” successor would lend himself or herself to manipulation by Beijing.

It’s unclear if his ambivalent stance is a protest against Beijing or a means for him to vent his frustration with the lack of unity among his people. But China accused the Dalai Lama of duplicity and flip-flopping, claiming that he is defaming Tibetan Buddhism “by doubting his reincarnation”: Just as the Dalai Lama did not decide on his birth, it was not his choice to make one now. Beijing stated that he was chosen following religious rules and historical traditions and with the government’s approval.

China reaffirmed its longstanding stance in 2023, stating that “the successor must be searched within China” and “the reincarnation must be approved by the central government” — a convention continuing from the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368).

China’s State Religious Affairs Bureau’s Order No. 5 of 2007 lays down specific regulations for the selection through the Golden Urn procedure. Article 2 of the Order prohibits the role of outside powers. Article 5 says the reincarnation is “subject to an application for approval”. Tibetans have decried any Chinese involvement in the process of succession in the past and there are likely to be questions over China’s moral authority to select the next Dalai Lama.

However, the Dalai Lama would still be under a lot of religious and social pressure over his rebirth, especially given his contentious claim that the next Dalai Lama could be born outside of China.

In theory, a person’s spirit can transcend state borders. For instance, Tawang is the birthplace of the sixth Dalai Lama, whereas Mongolia is the birthplace of the fourth. But, the issue, in reality, is about political legitimacy. China insists that the legitimacy of the reincarnated citizen is effectively established by the laws of the jurisdiction or by lex domicilii, even if the rebirth is sought through a divination. Beijing will, therefore, treat the succession issue as a state matter and it claims the moral right to exercise “recognitional legitimacy” by both domestic and international law and context.

Even though religion may transcend national boundaries, believers have their nationalities. The dispute over the reincarnation of the 11th Panchen Lama persists after the Dalai Lama’s chosen candidate, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, vanished. China selected a successor, Gyaincain Norbu, through the Golden Urn ritual in 1995. Norbu is considered a fake Panchen, but he is the vice-president of the Buddhist Association of China and officially recognised as the 11th Panchen Lama. More importantly, traditionally, the Panchen Lama has played a direct role in choosing almost all of the previous Dalai Lamas. The incumbent Panchen Lama is a member of the standing committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. As such, he will be required to acknowledge the next Dalai Lama.

As the spiritual leader of inner Asia, the Dalai Lama is a uniquely oriental phenomenon. Beijing dismisses any claim that the Dalai Lama’s successor can be found in the West or in India. Uncertainty permeates the entire Tibet lobby as well. To begin with, a gestation period will follow after the Dalai Lama is no more. Given China’s goals, forming a regency council (search team) would not be simple. In addition to the apparent sectarian differences, his succession may also be influenced by feudal aristocracy, family groups, and coteries. Whether his successor will sustain the momentum is another worry. The conflict would intensify should there be two Dalai Lamas. The exiles would reject any Beijing-chosen candidate, but Beijing would deploy its political prowess, economic arsenal, and media skills to gain international support for its chosen Dalai Lama. It is unlikely that states that practice Vajrayana, such as Bhutan, Mongolia, Russia and even India, will directly meddle in the selection process.

Stakes are rather high for Tibetans in exile. As they reach out to governments in the West to stop China from meddling in the succession process, they are unlikely to draw the attention of the US. The previous Trump administration had signed the Tibet Policy and Support Act of 2020 (TPSA) that stated that the succession issue should be left to the Tibetans. This time, the Trump administration has already shut down USAID, which used to give over $10 million on average annually to bolster Tibetan self-determination against China. This could have a direct impact on the succession issue.

Beijing, on the side, is hosting gatherings of academics and religious leaders to reaffirm the significance of government approval for the recognition of the reincarnated Tibetan religious leader.

Ideally, the Tibetan and Chinese Buddhists should aim to achieve a consensus on the succession issue. However, it seems unlikely given the current state of global flux and because of Donald Trump’s second tenure in the White House.