China’s Domestic Politics Are Driving the Belt and Road Initiative

Although analysts tend to focus on the geopolitical effects of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), these are incidental rather than its driving force. This is because the BRI is primarily about state-building, a process that involves the creation and maintenance of political and economic institutions. These institutions facilitate the reach of the state and the provision of public goods.

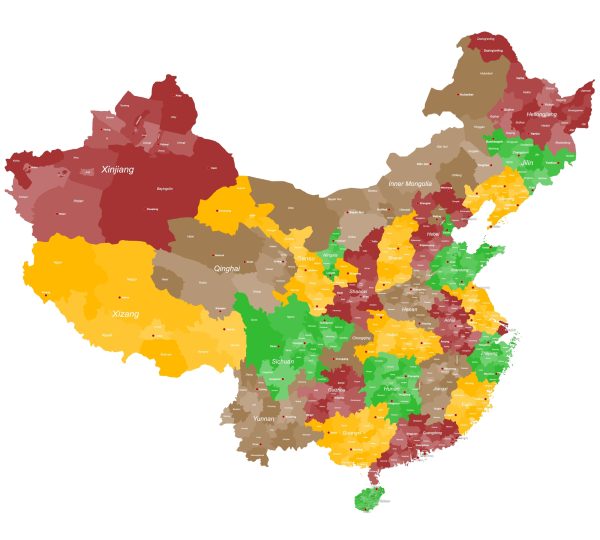

When Xi Jinping emerged as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2012, he announced the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation, the most recent iteration of Chinese state-building. This involved meeting two centenary goals of establishing a moderate prosperous society by 2021 and establishing a modern socialist country by 2049. At the heart of these two goals was the need to address the widening development gap between the coastal and interior provinces. This has been a long-running concern of CCP officials because of the perception that underdevelopment is the root cause of social instability, and therefore a threat to the survival of the party. The BRI serves as the primary vessel for state-building and addressing this issue by facilitating the integration of coastal and interior province economies, creating new cross-border supply chains, and securing new markets abroad.

However, despite its scale and scope, the BRI is not a fundamentally new project. It builds on previous state-building efforts dating back to the early 1990s. As the clearest evidence of this, five out of the six overland corridors that make up the BRI originated in provincial-level efforts. Two provinces have been key to this process. The first is Xinjiang, where a “Double-Opening” strategy in the 1990s sought to simultaneously integrate the province with the rest of China while also deepening economic links to its neighbors. The second is Yunnan, where the “Kunming Initiative” sought to do the same. In both cases, local officials positioned their provinces as gateways that connected China’s interior to markets abroad. This effectively made them domestic hubs for new domestic and international supply chains. As these initiatives gained traction, local officials lobbied central authorities for greater support. This resulted in national-level projects such as the Great Western Development (GWD) strategy, which incorporated these provincial initiatives.

Consequently, by the time that Xi announced the BRI in 2013, there were already two decades’ worth of expertise and infrastructure to build on. The Double-Opening strategy, subsumed by the GWD strategy, had effectively paved the way for the New Eurasian Landbridge, the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor, and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor under the BRI. Likewise, the Kunming Initiative, which was also integrated into the GWD strategy, had become the basis for the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor, the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor, and the more recently announced China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

Despite its origins, however, the BRI does offer something new. Whereas previous efforts primarily focused on hydrocarbon and mineral extraction, the BRI relies on promoting energy generation, industrialization, and connectivity. Beijing hopes that this process will produce more durable supply chains between China’s interior and foreign markets.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

In the context of Xinjiang and its neighbors, the BRI brought greater emphasis on connectivity where cities like Urumqi and Kashgar serve as trade hubs and landports like Horgos and Alashankou serve as gateways to Eurasian markets. Importantly, BRI connectivity investment goes beyond merely using Centra Asia and Pakistan as transit countries to reach other markets; it aims to promote local interconnectivity to improve transit times and reduce trade costs. The BRI thus means renovating existing roads and railways across Central Asia and Pakistan, as well as financing new ones. For example, in Kyrgyzstan this has involved the construction of the Alternate North-South Highway, whereas in Uzbekistan it was the Angren-Pap railway. These projects have been accompanied with significant investment in energy generation as well as the introduction of industrial parks and special economic zones to promote industrialization throughout Central Asia and Pakistan. All of these increase regional economic activity and connectivity, and facilitate the emergence of Xinjiang as the central hub linking China’s interior to emerging Eurasian supply chains.

In Yunnan, there is a similar effort to transform Kunming into a hub that connects China’s interior to external markets. The CCP has identified Yunnan as a pivotal province for the expansion and opening of border regions to create ports, border cities, and cross border economic cooperation zones. Central officials are emphasizing the construction of stable infrastructure, including roads, railways, pipelines, and power grids to enhance connectivity and economic development between Yunnan province and Southeast Asia. These proposed projects have come under the BRI umbrella and have a heavy emphasis on connecting China’s interior to Southeast Asia through Yunnan. The construction of cross-border highways, high-speed rail from Kunming, and hydropower represents a connecting flow of capital, people, and energy between Kunming and Southeast Asia.

To give a concrete example, with Chinese state-owned enterprise PowerChina publicizing its support in “charging” the Laotian “Battery of Southeast Asia,” the Laotian government plans to become a lead electrical exporter in Southeast Asia. This enables other states such as China, Vietnam, and Thailand to become major importers of Laotian electricity. China is also experiencing tight electricity supplies and with Laos making plans for a long-term 500-kilovolt transmission line that will connect to the Chinese grid via Yunnan, this becomes a large opportunity to address electricity supply issues.

The transformation of Yunnan into a regional hub has already shown results with the 2019 forum in Kunming hosted by the People’s Government of Yunnan Province and the China-ASEAN Center to discuss the cooperation on the BRI with both government and business officials from China and Southeast Asia.

Understanding the BRI as a form of state-building, driven by domestic Chinese politics, provides three important insights. The first is that with each iteration of state-building projects, the CCP became increasingly aware that the development of its interior provinces was predicated on the development of its neighbors. The assumption was that this would provide stability as well as the necessary economic foundations to sustain durable supply chains and markets for Chinese goods.

Second, while debt exposure in places like Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Laos merit concern, evidence suggests that China has not pursued “debt-trap diplomacy” predicated on asset seizures; rather, it has frequently resorted to deferrals, refinancing, or writing off loans. This tendency is driven by the logic of the first point.

The third point is that policy formulation and implementation guiding the BRI is negotiated by various local and central officials. As a result, its geopolitical effects are incidental rather than its driving force. Even if, over time, central officials sought to pursue geopolitical ends through the BRI, the fragmented nature of policy implementation in China, even in foreign policy, makes this more difficult than most analysts assume.