Making ‘Quad Plus’ a Reality

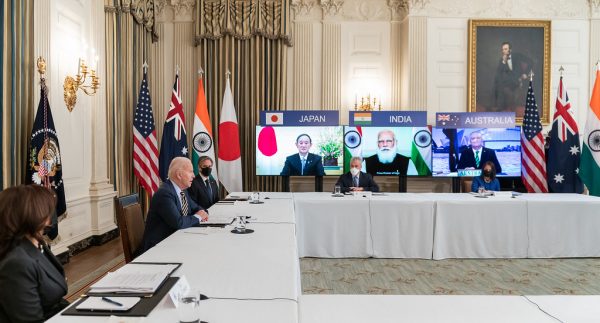

On January 6, 2022, Japan and Australia signed a “landmark” defense treaty, the Reciprocal Access Agreement, to elevate their bilateral defense cooperation in the face of China’s increasingly aggressive posture in the Indo-Pacific region. The joint statement explicitly mentioned the growing collaboration among the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) nations –Australia, India, Japan, and the United States – to “drive forward coordinated responses to the most pressing challenges” in the region. The “informal grouping” – sometime known as the Quad 2.0 – was revived in 2017 after a 10-year gap, and has since redoubled efforts to consolidate security partnerships and regional cooperation between members. The recently-concluded Australia-Japan treaty aims to inject further momentum to the Quad 2.0, which held its first-in-person leaders’ summit in September 2021, albeit under the shadow of the AUKUS (Australia-U.K.-U.S.) defense pact announcement. Notably, Tokyo is set to host the second Quad summit in 2022.

In this context, the concept of the “Quad Plus,” which has been in circulation for quite some time but remained abstract so far, becomes increasingly important in the current geopolitical scene, where post-AUKUS tensions are running high even among allies. How can the Quad Plus move beyond an abstract idea and consolidate as a regular political grouping?

In 2020, the Quad Plus framework found its first footing outside the parameters of roundtable conferences (where the idea has been in motion since 2013). On March 20, representatives from South Korea, Vietnam, and New Zealand were included in the weekly Quad meeting. In May, the intent for the Plus format was strengthened when the United States hosted a meeting of Quad nations, which also included Brazil, Israel, and South Korea, to discuss a global response to COVID-19.

The importance of multi-sectoral cooperation and convergence in the larger interest of the global community among like-minded countries is the need of this fragile post-COVID era. This is nowhere more apparent than in the Indo-Pacific, where the Quad intends to write “shared futures” through “new collaboration opportunities.”

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

The Quad Plus can represent one such critical opportunity. Moving forward, the Plus format can be framed as a “conjectural alliance” that abides by universalism, rule of law, democratic ideals, and free and open maritime domains. Overall, the idea of Quad Plus refers to a minilateral engagement in the Indo-Pacific that draws from the Quad to include other crucial emerging economies. At the same time, it offers a multipolar lens through which we can view, analyze, and assess the strategic multilateral growth of the nations involved.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Hence, it is not necessary to view the Quad Plus as an extension of the Quad. While the former has largely focused on creating a cooperative framework to tackle shared international challenges, like the pandemic-induced economic and public health concerns, the Quad has remained a more strategic dialogue that has looked at maritime, technological, infrastructural, and health challenges through the lens of security. Concurrently, the need to view the Plus framework in isolation is equally incorrect, especially with the release of the “Spirit of the Quad” joint statement, which highlighted the Quad’s own growing focus on avenues like global health, vaccination, infrastructure, critical technologies, and climate.

Rather, the Quad Plus must be viewed as link between the four founding nations and emerging global powers (via new joint initiatives or programs) that are relevant to regional prosperity, peace, and stability. Such a connect could perhaps first emerge on a rotational basis through bilateral, trilateral, and multilateral cooperation. The Quad’s outreach should not be limited to regional states (like Vietnam or South Korea) either, but also include like-minded partners in other regions such as the European Union and the U.K., which are stakeholders in the Indo-Pacific. The EU, for example, is a natural candidate owing to its close partnerships with India, Japan, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), particularly after the release of its Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific and the 300 billion-euro global connectivity strategy, Golden Gateway. So is the U.K., which has recently unveiled its Global Britain program that contains its own vision for the Indo-Pacific.

Expanding the Quad’s Horizons

The format will potentially expand the Quad’s horizons in terms of pluralism and inclusivity by inviting new and emerging powers to the fold. Such states can collaborate with the Quad’s new and niche initiatives (including its new working groups on climate and critical and emerging technology) to support, strengthen, and enhance value-driven, sustainable shared interests globally, as well as reiterate the support for ASEAN centrality. Moreover, Quad Plus partners can be included via newly-instituted projects like the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI, comprising Japan, Australia, and India), which seeks to reduce dependence on China and build resilient supply chains in the Indo-Pacific region.

Further, the implementation of national initiatives by Quad partners has enhanced the sphere of influence they wield, both individually and as a grouping, in the Indo-Pacific. By way of the Quad Plus narrative, an expanded outreach of ventures like Japan’s Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (EPQI), the U.S.-led Group of Seven (G-7) venture Build Back Better World (B3W), India’s Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI), Australia’s Pacific Step-Up, and the multilateral SCRI can, and must, be promoted. Quad Plus countries like Vietnam, New Zealand, Brazil, Israel, and South Korea can become crucial partners within such national initiatives.

Moreover, in the aftermath of the AUKUS announcement, which has caused a rift in Transatlantic ties, re-energizing Europe’s growing demands for strategic autonomy, the Quad Plus emerges as an expansion – not necessarily an extension – of the Quad. It will allow the creation of a “continental connect” and “corridor of communication,” revealing independent and direct links to Asian economies for the EU, beyond a U.S.-led entry.

Beyond Anti-China Rhetoric: Gains From Quad Plus

The Quad is a not a formal military alliance, even as it holds military/maritime drills like MALABAR among like-minded partners. However, in recent years, as the global geopolitical situation has worsened, the ongoing China-U.S. trade war has reignited the debate on the “Thucydides Trap.” At the same time, the post-COVID order has emphasized the “Kindleberger Trap” that posits China as a weak power in terms of providing public goods. Therefore, the Quad’s resurgence amid an increasingly volatile world and a militarist – though “weak” – China has given it a “new focus” to enhance “economic and environmental resilience,” as well as bolster “security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.”

The Quad has been particularly critical in escalating the bilateral and trilateral security cooperation between member states. Although the September 2021 Quad leaders’ joint statement doesn’t mention China explicitly, countering China is implicit in its strong tone pledging its commitment to security, “rooted in international law and undaunted by coercion.” Earlier, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi called the Quad 2.0 “an Indo-Pacific NATO” that “trumpet[s] the old-fashioned Cold War mentality to stir up confrontation among different groups.” The Chinese state media has called it “an empty talk club,” where “an anxious US wants to take charge”; while most recently, China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying termed it an “exclusive clique.”

Against this scenario, the Quad Plus can emerge as an intermediary or pacifier with its intent to go beyond the China trope: While accepting realistic national security threats, a Quad Plus system allows participating nations to create a strategic alignment that might indicate a growing, or temporary, embrace of a U.S.-led order in the Indo-Pacific region while still not becoming part of a set “alliance framework.” Here, it is important to remember that countries like South Korea, New Zealand, and Vietnam were largely included in the format because of their success in handling the COVID-19 pandemic within their borders.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

However, should the Quad Plus format gain new impetus and new objectives, these states will likely not be willing to openly participate in or espouse any format that appears to be China-centric (or rather, anti-China), while they share elaborate economic ties with Beijing. Even though economic and trade ties with China are witnessing more scrutiny in the post-COVID-19 order, with nations aiming to create more resilient and sustainable supply chains, China’s vise-like hold on the world economy is unlikely to be upended. Nonetheless, there are ways to reduce the global reliance on China – as the SCRI highlighted through its efforts to explore possibilities for diversification via collaborations of like-minded countries and public-private partnership programs. Additionally, the Quad Plus could also consider making room for China, which is still a dominant economic force, in its dialogue mechanism so as to promote China-U.S. bonhomie in the interest of safeguarding regional prosperity and stability.

Ultimately, the Quad Plus format is now its nascent stages; however uncertain, its future holds immense potential. In a post-COVID-19 world, where the pre-existing economic and political vulnerabilities have exacerbated and created havoc, this kind of alternative framework could not only help facilitate the provision of global public goods, but also reconfigure the global governance systems – and therein lies the essential capital of a Quad Plus grouping.