‘No Limits’? Understanding China’s Engagement With Russia on Ukraine

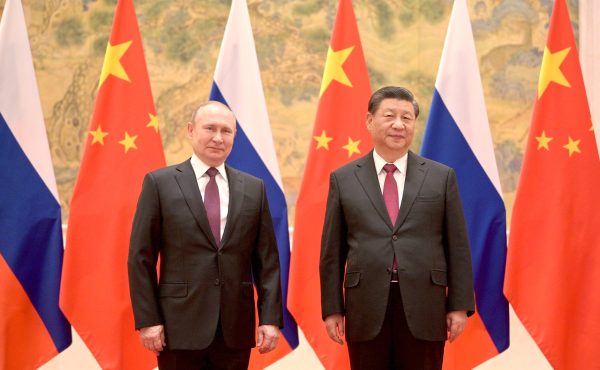

Vladimir Putin’s last visit to China took less than half a day. The Russian president landed in Beijing on the afternoon of February 4 and left for Moscow the same day, shortly after the evening Opening Ceremony of the Winter Olympics. Putin didn’t even attend the next day’s banquet, at which Chinese President Xi Jinping toasted foreign dignitaries. To fit in with the Russian leader’s tight schedule, Xi arrived at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse instead of receiving Putin, like the other guests, at the Great Hall of the People.

There is much speculation on whether the primary purpose of Putin’s swift visit was to brief the Chinese leader on the upcoming military operation in Ukraine and secure Beijing’s backing. Many believe that, yes, Xi knew everything in advance; moreover, some say Xi specifically asked Putin to carry out the operation only after the Olympics’ Closing Ceremony.

There is little evidence that the two leaders’ talks and working dinner on February 4 focused on the internal dynamics in Ukraine. Still, NATO and the activities of U.S.-centric alliances in the Asia-Pacific may well have been discussed. While Ukraine is totally absent from the joint statement approved by Putin and Xi, criticism of the Western bloc’s policies affecting the two countries’ security is prominently present.

Instead of trying to read the tea leaves and looking for evidence of collusion between Moscow and Beijing, it is more helpful to look at how the logic of bilateral relations and the national interests of each side have manifested in the current crisis.

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

Cross-Interests or a Side Story?

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

The Ukrainian case is unique and apparently unprecedented in the history of Sino-Russian relations. For the first time, China has to determine its position regarding a full-scale military conflict in Europe involving two post-Soviet countries, one of which is Beijing’s closest strategic partner.

The level of mutual understanding between Putin and Xi is so high that, while the escalation was on the horizon in early February, the top Chinese leadership had no reason to worry about any adverse effect on the Beijing Olympics. It looks like Moscow itself did not want to repeat the awkward timing of the Russian “peace enforcement” operation in Georgia, which happened to coincide with the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.

On the other hand, despite ever-growing military ties, Russia and China are not allies. Top-level coordination on Russia’s upcoming military moves would make sense if China were somehow a contributor to the operation along with the Russian Army. Clearly, any such joint operation option is off the table, and the parties, valuing their mutual trust, retain a high degree of strategic autonomy.

The Russian president once admitted that Xi never pushed him on the issue of the South China Sea, a strategically important asset for Beijing but a more complicated topic for Russia. “You know, I’ve developed a very good relationship based on trust with President Xi Jinping. I would say a friendly relationship. However, he has never – I would like to underscore this – he has never asked me to comment on this issue or intervene in any way. Nothing of the kind has ever passed his lips,” Putin revealed to journalists after the 2016 G20 Summit in Hangzhou.

While China and Russia have divergent regional strategic interests, they may still have overlaps in regional affairs. Analysts focusing on Moscow and Beijing’s recent mounting criticism of NATO have so far overlooked an important development in Sino-Russian ties: namely, that the phrase “common adjacent regions” appeared for the first time in the joint statement of February 4. The document notes that China and Russia oppose external forces undermining security and stability in the two countries’ “common adjacent regions.” It is not difficult to guess that this refers to the states of Central Asia.

After the rapid and effective use of the Russian-led CSTO peacekeeping force in Kazakhstan in January, China felt that it needs to better use Moscow’s political, military, and diplomatic potential. The turmoil in Kazakhstan made clear that Russia has a clearer understanding of what is going on inside Central Asian elite circles. Beijing assumes that calm in the region is vital for ensuring stability in Xinjiang; accordingly, the political dynamics of Central Asia are an important variable in the Chinese leadership’s internal security formula. Recent events in Afghanistan add substantial weight to this variable.

Ukraine, however, does not play a role comparable to Central Asia in terms of the sustainability of the political regime in China. In fact, Xi and Putin do not perceive the Ukrainian issue as a matter of common and long-term interest. Obviously, there are countries in the post-Soviet space that are positioned at the intersection of Russian and Chinese core interests and require deeper coordination, but these do not include Ukraine or Belarus.

Two Contours: Internal and External

When discussing the convergence of the Russian and Chinese narratives on Ukraine, a striking difference is often overlooked. In the Ukrainian situation, we can distinguish between internal and external contours. The external one concerns Ukraine’s relations with NATO and the collective West. The internal one is related to the situation inside the country – the status of the pro-Russian regions and the very nature of the current Ukrainian regime.

Despite the increased proximity between the Chinese and Russian positions, China has made no mention of the second set of issues, which play an important role in Russia’s rationale for its “special military operation.” China has made no pronouncements on Russia’s desire to “denazify and demilitarize” Ukraine. The Chinese narrative has lacked references to the “armed coup of 2014,” the “illegal transfer of power to the junta,” and “Nazi occupants in Kyiv,” which are common in Russian propaganda and at the official level. The Chinese silence can hardly be seen as a tacit agreement with Russian talking points – rather the opposite. This is where the division between the positions of Moscow and Beijing runs.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

The situation is multilayered, so China’s reaction will also be diverse and accommodate Russia’s interests to varying degrees. The most severe constraints are related to the principle of respect for territorial integrity, which is crucial for China in connection with Taiwan. This principle concerns one fundamental choice: the recognition or non-recognition of the republics in Eastern Ukraine. Here, China’s positioning is clear: as with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, there will be no recognition of the two republics in eastern Ukraine that the Kremlin has already recognized. Nevertheless, at the onset of the crisis, Xi expressed understanding of Russia’s motives by rhetorically supporting Moscow’s narrative that the West is to blame for the situation and calling for a security system that takes Russian interests into account.

Still, when it became clear that the combat operations would be protracted and endanger the life of Chinese nationals in Ukraine, Beijing made clear that the current situation is not what China would like to see. The argument that the ongoing crisis results from the West’s harmful influence in Ukraine sometimes even takes a back seat. As Foreign Minister Wang Yi put it at a press conference on March 7, the Ukraine issue arose from contention between two countries, namely Russia and Ukraine. Such statements demonstrate that if the historical roots of the problem are treated as a clash between two national narratives, China prefers to acknowledge the “complexity” of the situation but distances itself from expressing its own opinion.

Unlimited Friendship Under Political Constraints

As a rising power with a wide array of interests, China will undoubtedly keep an eye on the global reaction to the Ukraine crisis. The more substantial Western consolidation becomes, the less space China will have to support Moscow out of fear of secondary sanctions. It is possible that, as with the 2014 sanctions following Russia’s actions in Crimea, Chinese companies will de facto comply with Western sanctions, or even over-comply, for fear of damaging China’s global economic interests due to actions in the grey zone. China must consider that it is much more closely integrated into the global financial and economic system than Russia.

However, Xi Jinping’s primary concern is that Beijing not be associated with the conflict, so the priority choice will still be a neutral position. At the same time, Moscow can be confident that China will not criticize Russia or impose sanctions both in bilateral contacts and on international platforms. As for the role of mediator, China will neither get deeply involved in the crisis nor act as a third party in Russia’s relations with the West.

So, what lies ahead for the Kremlin and Zhongnanhai? The impact of the Ukrainian crisis is based on its complex and contradictory content, which covers both an open area, on which China and Russia – who oppose Western domination – speak out clearly and act accordingly, and a grey area – relating to Ukraine’s internal politics – where Moscow is not inclined to seek Beijing’s support and Beijing prefers not to speak out.

In January 2021, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reiterated that Sino-Russian strategic cooperation has no end limits, no forbidden areas, and no upper bound (meiyou zhijing, meiyou jinqu, meiyou shangxian). Chinese scholar Zhang Xin then suggested that the “no-limits” formula provides “a vague, but flexible and large enough space for imagination in conceptualizing the bilateral relationship.” The inclusion of the formula in the recent joint statement is certainly worthy of attention, but it is also important to note that it refers to the absence of limits in the “friendship,” a category that is more moral than related to realpolitik, which is the framework in which the relations between Russia and China are progressing.

In 2020, my colleague Ivan Safranchuk and I pondered the limits of convergence between China’s and Russia’s positions on the Black Sea. Our conclusions are also relevant today. We noticed at the time that as long as Black Sea affairs were driven primarily by regional dynamics (even if there is some involvement by great powers), Russia and China did not form a common front. However, as Black Sea affairs become a facet of great power competition between the United States and Russia, Moscow and Beijing grew more united in the region.

Even if Putin and Xi discussed the Ukraine problem at their February 4 summit, this was likely limited to areas where China and Russia can speak with one voice. The widespread interpretation of what “no limits” in cooperation means is most likely misunderstood with regard to current Sino-Russian relations. There is good news and bad news for those concerned by the idea that the Moscow-Beijing axis is already acting in full swing and the two sides have merged to the point of appearing on the world stage as a single actor. The bad news is that Russia and China can already read each other’s minds with reasonable accuracy. The good news is that their thoughts and actions may not necessarily be the same on every occasion.