The Death of Hong Kong’s University Student Unions

Student societies have long played an important role in Hong Kong activism. Now they are dying out amid the wider crackdown on dissent.

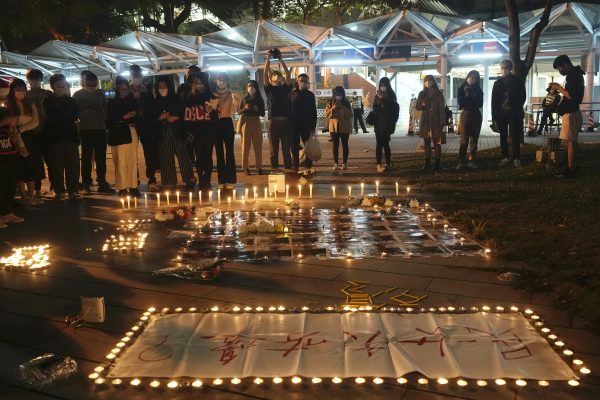

University students light candles at the site after the “Goddess of Democracy” statue, a memorial for those killed in the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, was removed from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Friday, Dec. 24, 2021.

Not long after the Pillar of Shame was dismantled on the University of Hong Kong campus and covered by bright yellow construction boards, there was another construction project underway not far away.

A slogan, painted by the university’s student union on a paved road decades ago and also commemorating the Tiananmen Massacre, was covered with tar by workers, though the university insisted that it was routine maintenance. The student union had originally painted this protest piece; now there was no student union left in the university to protest this move.

Hong Kong’s student societies have historically played an important role in social activism and driving society’s political narratives. After a violent anti-colonial riot in 1967, locals learned that organized protests are the only way to be heard under an unelected and non-democratic colonial government.

Student activists, whose interests in political and social affairs boomed at that time, were always at the forefront of protests. In the decade that followed, student activist groups became the foundation where Hong Kong nurtured a generation of business and political leaders. Even the city’s current leader Carrie Lam was a student activist herself before joining the colonial government; she was involved in numerous sit-in protests.

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

Much of the activism was driven by a consolidating sense of identification with Hong Kong, along with hints of anti-colonialism and Chinese patriotism. Beijing-sympathetic student activists led patriotic protests and visited mainland China.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Student activists shifted their cause from being pro-China to realizing a “democratic unification” to China as negotiations about Hong Kong’s eventual handover began. Hong Kong was to gradually fully democratize under Beijing’s promise and the expectation that China would one day become a democracy.

Dr. Simon Shen, a Hong Kong scholar on international affairs, noted that most of the city’s progressive ideas evolved from the student unions.

“It served as the forerunners of HK’s civil society after the 1967 Riots, as part of the colonial regime’s attempt to develop an incremental approach of democratization,” Shen told The Diplomat in an email.

After the Tiananmen massacre in 1989, which shook Hong Kong and the rest of the world, student unions and pro-democratic politicians continued to press the cause of democracy. Their roles drove the agenda of civil society through to Hong Kong’s handover back to mainland China in 1997 and beyond.

The 2014 Umbrella Movement became a turning point. Student unions across Hong Kong’s tertiary education institutions joined the 79-day sit-in demanding universal suffrage. Student leaders like Joshua Wong, Nathan Law, and Agnes Chow rose to international prominence as the leading figures of the movement.

The movement’s eventual failure pushed activism and democratization into disarray, which were reignited in 2019 by the pro-democracy protests. Student unions contributed independently and played a significant role in keeping the protests’ momentum alive.

The unions were vocal in their criticisms against the government. Some union members also actively discussed the possibility of Hong Kong independence, a strong political taboo that Beijing – and some university presidents – could not tolerate.

Student unions hence became the authorities’ target after the National Security Law was introduced, as all forms of dissent could now be criminalized. Unions across Hong Kong’s universities soon disbanded or were disavowed in a similar manner, with the last student union disbanded in April 2022.

The University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s student union was forced to disband last August after posting a social media feed expressing sympathy toward the assailant in an attack on a police officer. The attacker stabbed the patrolling officer and committed suicide on the scene. The act drew sympathy from parts of the population as bitter memories of police brutality during the 2019 protests still lingered. Spontaneous vigils at the scene were quickly dispersed by police.

The university was quick to disavow the union. Four members were arrested for “glorifying terrorism” and authorities suggested that domestic terrorism was infiltrating university campuses.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Student unions “have wantonly instilled among students improper values and disseminated false or biased messages in an attempt to incite their hatred against the country and the [government], or even advocated the resort to violence and illegal acts for political ends,” Security Secretary Christopher Tang said during a Legislative Council hearing.

“People sympathizing with violent attacks are prone to further radicalization and becoming supporters, who could then easily turn into participants of terrorist activities,” he added.

The city’s former leader, Leung Chun-Ying, also pulled no punches in criticizing student unions’ role in politics. He believed that their cause for self-determination is at odds with Beijing’s National Security Law and would only grow if unchecked.

“A child who steals a needle will grow up to steal gold,” he said in an interview with South China Morning Post. “We need to care for the young. We cannot afford to underestimate the seriousness of the problem; tolerance will only cause more widespread harm.”

In February, members of City University’s student union posted and recited slogans calling for freedom of thought and defiance when being evicted from their office by campus security. This attracted an investigation from the National Security Police, which said the act violated the National Security Law.

The university’s facility management office sent emails to some 30 students involved two months after the incident. It demanded to know whether they would admit to breaching the colonial-era anti-sedition laws during their “unnecessary gathering.”

The university urged the public not to intervene with its administration, despite previously denying any knowledge regarding the email sent .

In the meantime, Lingnan University ceased collecting membership fees on their student union’s behalf, saying the long-practiced arrangement was inappropriate. The affected student bodies alleged that the decision was due to pressure from the authorities.

Shen, who had ties with different university unions before relocating to Taiwan, believes the moves are part of Beijing’s plan to isolate individuals “into mere atoms.” Hong Kong’s traditional bottom-up civil society model poses particular concern, and Chinese authorities are keen to pull it up by the roots.

“Ideas exchange would be severely restricted on campus in the future,” Shen said.

Around 50 civil society groups have already disbanded since Beijing enforced the National Security Law. University campuses – and society as a whole – are now virtually free of dissident voices.

A report from the Global Public Policy Institute in 2020 ranked Hong Kong’s academic freedom lower than that of Russia and Cambodia. The report specifically listed the demise of student unions as a contributing factor.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam defended the overhauls in the city’s universities by warning of infiltration by “external forces with ulterior motives.” Those “forces,” she claimed, are indoctrinating students into taking part in illegal activities.

“I would urge the university management, the council chairman, and the president to be extremely careful and to make sure that university students will not be easily indoctrinated by [anti-China] prejudices and biases, let alone to take part in activities that will breach the laws of Hong Kong,” Lam said, responding to a question from a journalist about students being paid to join protests.

The severity of the change in Hong Kong’s universities is evident from the exit figures. In the 2020-21 academic year, the dropout rate of tertiary students climbed by over 20 percent, reaching 2,600. The exodus is partly linked to the ongoing brain drain that dates back to the enactment of the National Security Law.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

For the most part, it is business as usual on university grounds. Recruitment banners for student clubs remain pinned on billboards, and students are still scattered across the campus engaged in their usual activities, as most classes were moved online.

But there are changes for those observant enough to notice. Any markings of the student unions were crossed out as they were left hanging on an empty and sterile campus, and Lennon Walls, once frequented by students and activists, are now cordoned off and thoroughly scrubbed clean.

All hints of Hong Kong’s once-thriving student activism, like the slogan on the paved road and the memories behind it, have been swept away.

This article has been updated to reflect the disbanding of HKPU’s student union.