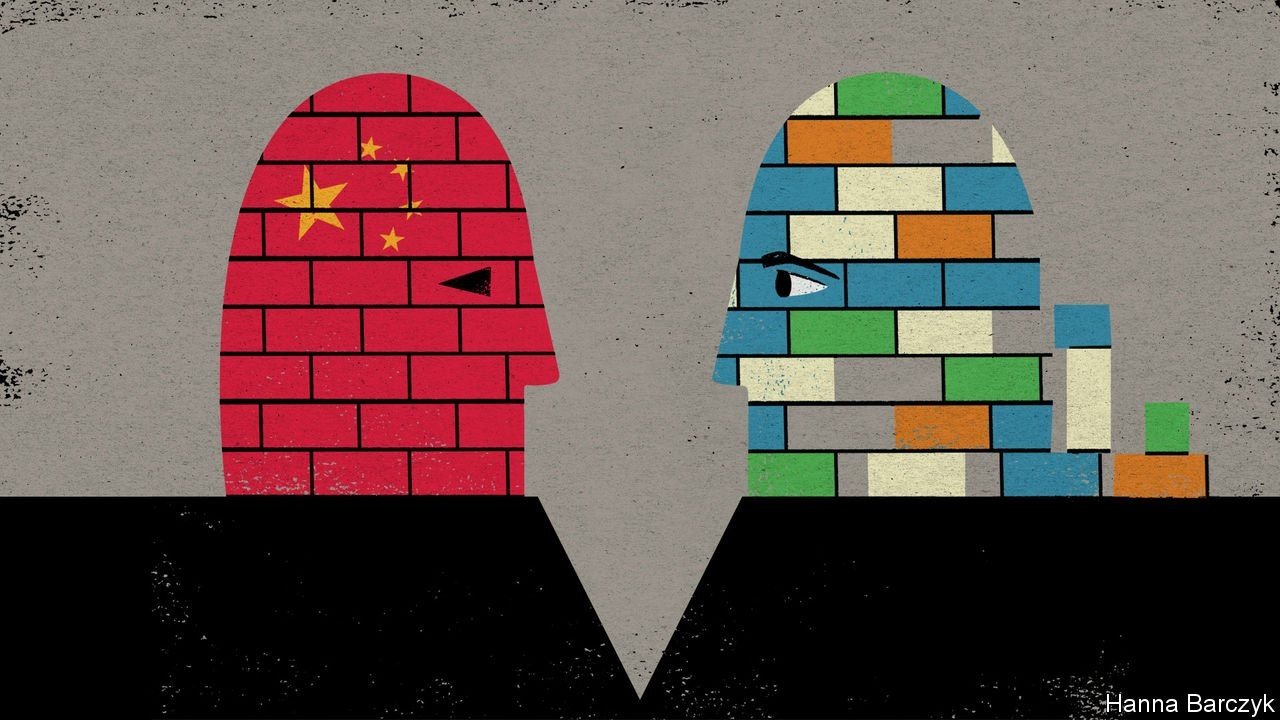

China wants the world to know that resistance to its rise is futile

L EERS OF CHINA and America share an obsession: the notion that a large enough coalition of Western democracies might have the heft to confront a rising China about its authoritarian, state-capitalist ways, and demand that it follow a new trajectory, one that does less damage to norms and universal values that have governed the rich world since 1945.

Listen to this story Your browser does not support the

China fears a broad, American-led coalition as the one force that might still be able to contain it. Not so long ago its foreign minister, Wang Yi, mocked the Quad, an informal group uniting America, Australia, India and Japan, as so much “sea foam”. After America hosted a Quad-leaders summit, China has called the group a destabilising scheme to build an Asian NATO . The Trump administration expanded the role of the Five Eyes, an intelligence-sharing pact between America, Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand. The group issued a statement in November 2020 about the crushing of political freedoms in Hong Kong. But the Five Eyes should be careful not to be “poked and blinded”, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman growled. Australia and Canada are being punished with trade sanctions and detention of their citizens to teach them the cost of helping America in disputes with China.

Under President Joe Biden, American enthusiasm for coalition-building has only grown. The secretary of state, Antony Blinken, explained to CBS News recently why America seeks allies to confront China’s government about repression at home and aggression overseas, as well as its adversarial approach to trade. “We’re much more effective and stronger when we’re bringing like-minded and similarly aggrieved countries together to say to Beijing: ‘This can’t stand and it won’t stand’,” Mr Blinken said.

In fact, these two rival powers are obsessing about something that is not likely to happen. For one thing, America’s allies have few illusions that any group of outsiders, even one led from Washington, can tell today’s China what will and will not stand. As a Western diplomat in Beijing glumly notes, such countries as Britain, France and Germany “are close to accepting the inevitability of China’s rise”, and so are out of alignment with America. For another, lots of Western democracies are fractious and mistrustful, especially after four years of Trumpian bridge-burning. European and Asian democracies alike are wary of joining America in anything resembling a cold-war effort to check China’s aggression—especially if it jeopardises profitable trade relationships.

France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, said this year that it would be counter-productive for Western powers “to join all together against China”. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, has also spoken out against the “building of blocs”. In recent telephone and video calls with President Xi Jinping and other Chinese leaders, there is no record of her raising sweeping sanctions imposed by China on European politicians and researchers, in retaliation for EU sanctions targeting officials accused of brutally repressing Muslims in the north-western region of Xinjiang.

Official read-outs instead record Mrs Merkel talking of co-operation and praising a draft trade pact agreed with China last year, the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, which would offer more access to China’s market for some EU firms, notably German carmakers. Ironically, the agreement may be doomed by the sanctions that Mrs Merkel wants to ignore. Those punished by China include members of the European Parliament, which must approve the pact. The EU trade commissioner, Valdis Dombrovskis, said on May 4th that efforts to finalise the deal are on hold.

EU unity is further undermined by members with close investment ties to China, such as Greece. One member does not conceal its admiration for Chinese autocracy, charges a European diplomat in Beijing: “The EU has its traitor in the ranks: Hungary.” Nor is there consensus within the Five Eyes. In recent weeks, New Zealand’s government declared itself uncomfortable with the intelligence-sharing pact’s releasing geopolitical statements.

China loves all such signs of disunity, praising European nations for seeking “strategic autonomy”, a French phrase that means not marching in lockstep with America. Yet in its paranoia about American-led alliances bent on containment, China risks missing a change that is actually happening in the real world.

Even as they concede that the time for trying to change China is over, rich-world democracies are defensively China-proofing their economies and their societies. They are setting up new investment-screening laws, investigating whether foreign powers are meddling in their domestic politics and universities, and writing public-procurement rules to block bidders who raise national-security concerns. The EU is proposing new curbs on state-subsidised firms wanting to compete in European markets. Such policies do not always name China, but it is the target.

Standing together, sort of

Foreign ministers of the G 7 countries—America, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy and Japan—met in London on May 3rd-5th. Their closing communiqué condemns Chinese abuses in Xinjiang, including “the existence of a large-scale network of ‘political re-education’ camps, and reports of forced labour systems and forced sterilisation”. The solutions offered are purely defensive, and make no pretence that the G 7 can change Chinese policies. The risk of importing goods made with forced labour will have to be tackled through “our own available domestic means”, the ministers say, by raising awareness and advising businesses.

Such words do not frighten China. Confident in the power offered by its vast market, it hopes that foreign governments will hurry up and realise that resistance to its rise is futile. If resistance means forming blocs to contain China, then America’s allies already agree. But those same democracies are also channelling a growing distrust into defences that will introduce new frictions into relations with China. Friction is a form of resistance, too. ■