China might fuel the fire by building the “largest” dam in the world on the Brahmaputra River in India.

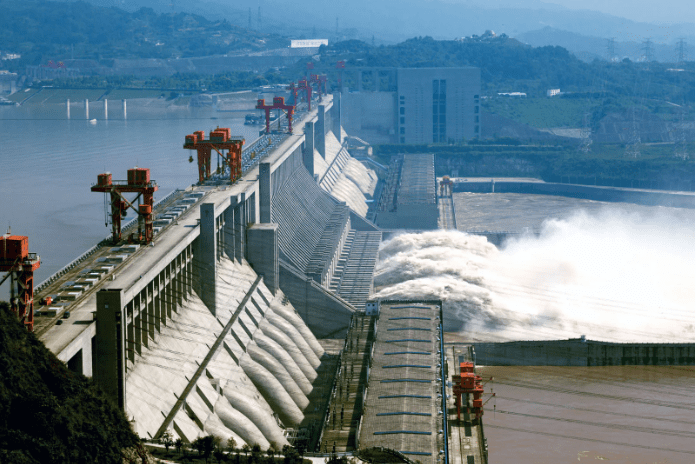

Its own “Three Gorges Dam,” now the greatest hydroelectric plant in the world, will be dwarfed both in size and capacity by China’s mega project, with a projected capacity of 60 gigawatts, which will be built close to its highly fortified border with India.

There are sporadic media reports on China’s dam-building activities, but since China never specifies the size and geographic scope of these projects, they remain a mystery.

The 3,969-kilometer transboundary stream Yarlung-Tsangpo/Brahmaputra, which rises on the Angsi Glacier close to Mount Kailash and is encircled by the arms of the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis, is a significant river system with different climatic and hydrologic zones.

Originating in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), the Yarlung Zangbo eventually creates the delta in Bangladesh after flowing into India as the Brahmaputra.

After traveling 1,100 kilometers eastward and receiving several tributaries, the river abruptly turns to the northeast and follows a path through a series of large, narrow gorges between mountainous massifs at the eastern end of the Himalayas. The river then turns southward and crosses the China-India Line of Actual Control (LAC), with canyon walls rising upward for at least 5,000 meters on either side, creating a deep gorge (the “Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon”) as it does

According to the amount of water released (19,825 cubic feet per second), it is the ninth-largest river in the world.

At the point on the Yarlung-Tsangpo/Brahmaputra where the river makes a steep knee bend (u-turn) before entering India, it is claimed that China intends to produce hydroelectric power.

The Chinese state-run tabloid Global Times said that when information on the dam surfaced again in November 2020, “China will build a hydropower project on the Yarlung-Tsangpo River, one of the major waters in Asia that also passes through India and Bangladesh.”

There is no precedent for this project in history, and it will be a historic chance for the Chinese hydropower sector, according to Powerchina’s chairman. He had said that the dam will help Beijing reach its clean energy targets by producing 300 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) of clean, renewable, and carbon-free power each year. These claims persisted far into 2021 and have now reappeared.

In order to alleviate water shortages in certain regions of the nation, China may potentially redirect the river towards the north. Either a decrease in water flow or a terrible ecological upheaval would be the consequences for India.

According to conservative estimates, China intends to build around 100 dams to harness the electricity of significant rivers emerging in Tibet. Brahma Chellaney, a geopolitical expert, claims that China is “engaging in the greatest water grab in history” by constructing several dams on all of the major rivers that originate from the Tibetan plateau.

Small dams along the Yarlung-Tsangpo’s main channel are said to have been built by China, and now there may be plans in motion for the construction of larger dams.

In January of this year, geospatial intelligence researcher Damien Symon used satellite images to determine that one of these smaller dams is being built on the Mabja Zangbo (Tsangpo) river in Tibet’s Burang County, only a few kilometers north of the Indian, Nepali, and Chinese borders.

While the structure isn’t finished, the project will cause worries about China’s potential future water management in the area, according to his tweet. The pictures illustrate the construction of a reservoir and an embankment-style dam.

An established Chinese presence has replaced earlier crude posts on the Chinese side of the Line of Actual Control, according to a new Chatham House analysis by Symon using satellite imagery obtained in the months beginning in October 2022.

Even if this has nothing to do with the construction of dams, it nevertheless shows that the Himalayan boundary continues to be unstable in certain places.

A lower riparian cannot veto a higher riparian’s interventions in a river under customary international law, which is based on the 1968 Helsinki Rules and the 1997 UN Convention on Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses.

However, a lower riparian, in this case India, has the right to request advance notification of the intention to intervene, full technical information, due consideration for the lower riparian’s concerns, advance consultations, and acceptance of the principle of avoidance of “substantial harm” or “significant injury” to the lower riparian. The issue still stands: Will China take India’s worries into consideration?

In accordance with a 2002 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), China must provide hydrological data on the Yarlung-Tsangpo/Brahmaputra between May and October so that downstream India might be informed in the event of a large flow rate during the monsoon season.

However, following the 2017 Doklam border standoff, when China unexpectedly ceased sharing water flow data, India became apprehensive of China’s propensity to withhold information on river condition.

Any unilateral hydroelectric project in China must have a comprehensive strategy engaging all riparian countries to prevent the possibility of a protracted conflict.

For the time being, the building of dams along the Yarlung-Tsangpo-Brahmaputra’s route poses a potential to escalate already existing conflicts over China’s expanding regional dominance.