Joe Biden’s government has not yet committed to a path on trade in technology with China

T HE PROCESS of filling vacancies at the Bureau of Industry and Security ( BIS ) does not normally make the news. An agency of the Department of Commerce, BIS is tasked with running America’s export-control regulations. These rules were originally designed to prevent the components of weapons of mass destruction from being shipped off to terrorists. The work of overseeing them was important public service, but carried out in the background, away from the public eye.

Listen to this story Your browser does not support the

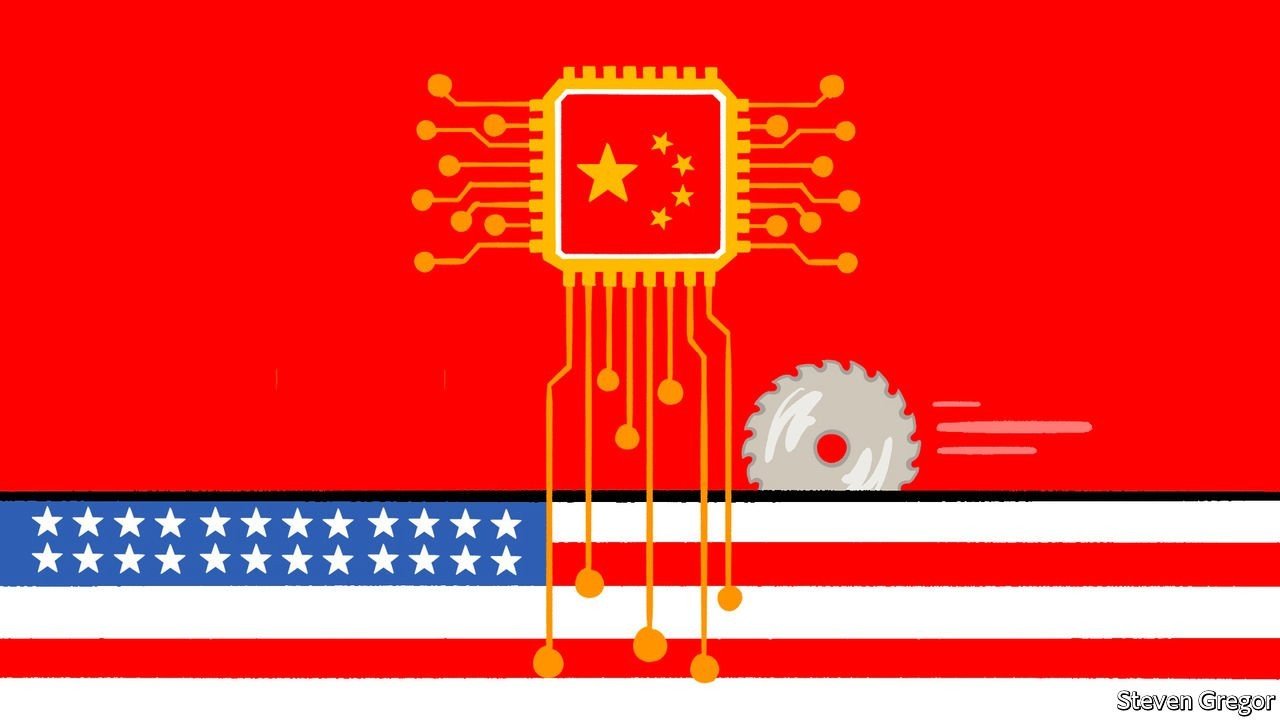

Donald Trump’s presidency changed that. He and the China hawks in his administration repurposed BIS and its regulations as a weapon against China’s technological ascendancy. They rewrote the rules several times between 2018 and 2020 in an escalating series of attempts to cut off Huawei, a Chinese technology giant, from global semiconductor supply chains. Huawei has reported declining revenue in its two most recent financial quarters as a result, proving that America can use export controls to disrupt Chinese technological development, at least in the short term.

This put BIS right in the middle of America’s biggest foreign-policy challenge, containing China’s rise. Speculation about its leadership began soon after Mr Biden took office. But the chaotic methods of Mr Trump’s administration created a new political dynamic around the agency. The repurposing of regulations often left gaps between what the new rules actually said and what the Trump administration claimed they meant for China in speeches and press releases. Lawyers advised their clients to follow the rules to the letter, thereby allowing them to carry on doing business with Chinese entities where it was still legal to do so.

The result is that many export-control experts were seen as “soft on China”. On May 4th a Republican congressman from Texas, Michael McCaul, called on the president to nominate a candidate that has “real national-security experience, deep knowledge of the CCP , and will not be conflicted by deep ties to industry”.

It is this sort of rhetoric that has driven the administration’s consideration of “outsider” candidates who do not carry the damaging expert label. The archetype is James Mulvenon, a defence analyst who became known in Washington last year for authorship of a report linking SMIC , China’s leading chipmaker, with the People’s Liberation Army. That Mr Mulvenon has even been under consideration demonstrates how far the role of BIS and the politics around it have shifted, as he is not a lawyer and has no experience administering or complying with export-control regulations. Barack Obama appointed a lawyer, George W. Bush a tech-company boss. The post was vacant for most of Mr Trump’s term; hence, in part, the chaos.

Political appointees do not determine policy, but rather implement what flows from the government, and from the National Security Council ( NSC ) in particular. Mr Biden’s NSC contains plenty of expertise on China and technology. Saif Khan, the council’s Director for Technology and National Security, published a paper in January which laid out a plan for curtailing Chinese semiconductor development. Its other members want to develop a tough new line, less for the industrial-competition reasons that motivated Mr Trump and his administration than because of the technology-enabled human-rights abuses that the Chinese government is perpetrating in Xinjiang and beyond. Yet the plan, at present, appears to be unfinished. People close to Mr Biden’s staff say that policy on China and technology remains undecided.

The choice of an under-secretary to run BIS , when it is made, will be a sign of whether the Biden administration has a real plan. If the president chooses someone with little to no experience with export-control law, but who has a hard line on China, that will indicate that domestic politics are dominating the administration’s thinking and that it lacks the confidence to fend off critics like Mr McCaul. The appointment of someone who knows the law and can carry out the government’s bidding quickly would suggest that Mr Biden does, indeed, have a plan for redrawing the lines of technological trade with China, and that he intends to use the most experienced people possible to do so. ■

For more coverage of Joe Biden’s presidency, visit our dedicated hub