‘There is still so much hatred’: looking back on Holocaust documentary The Last Days

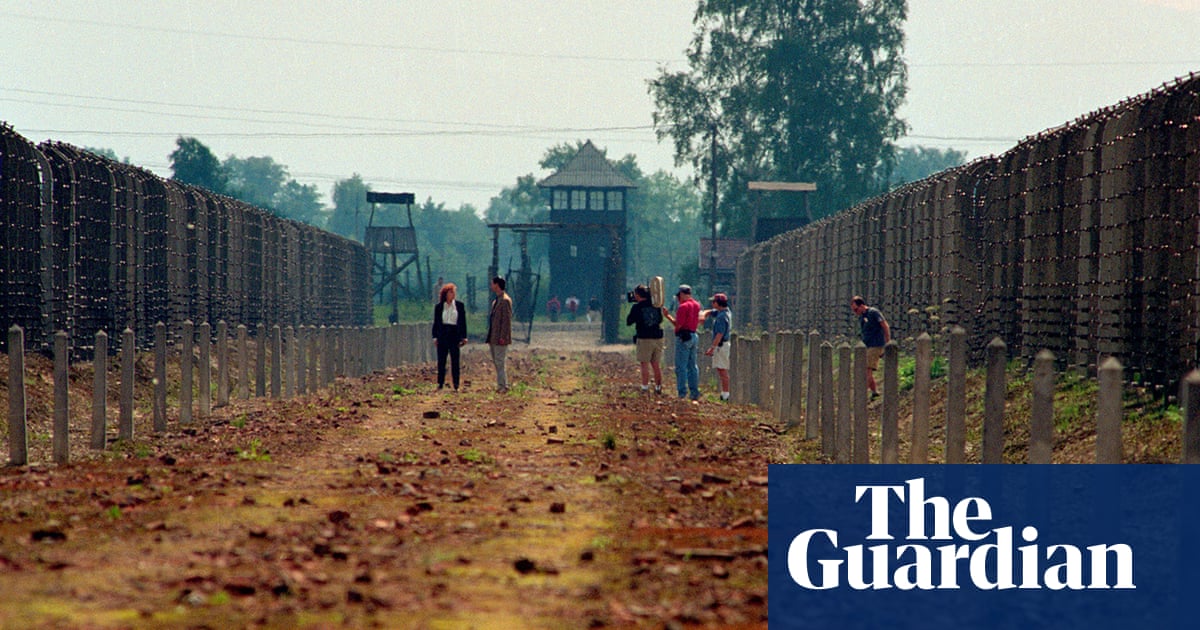

Show caption Filming The Last Days at Auschwitz. Photograph: Focus Features Documentary films ‘There is still so much hatred’: looking back on Holocaust documentary The Last Days The makers of 1998’s Oscar-winning film, along with one of its subjects, discuss why a remastered version landing on Netflix still has much to teach us Radheyan Simonpillai Tue 18 May 2021 15.54 BST Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

The last time June Beallor saw the Auschwitz survivor Irene Zisblatt, they watched Sex and the City together. That was 20 years ago.

Beallor is one of the producers behind The Last Days, the Oscar-winning 1998 documentary executive-produced by Steven Spielberg about the Hungarian Jewish experience during the Holocaust, which has now been remastered and re-released on Netflix. Zisblatt, who escaped from Auschwitz as a teen, is one of the film’s subjects. The 91-year-old is also a big fan of Sex and the City. Her favourite character is Carrie Bradshaw, the fashion columnist played by Sarah Jessica Parker, because “she was always looking for the next thing”.

On a Zoom call with the Guardian, they reminisce about that get-together at Beallor’s California home. She was hosting a reunion for the people involved with The Last Days. The director, James Moll, missed the festivities because he was out of town filming. But fellow Holocaust survivors Bill Basch, Alice Lok Cahana and Renee Firestone and the associate producers Bonnie Samotin and Elyse Katz all attended the poolside gathering, which took place on a Sunday.

Beallor recalled one of the producers mentioning in hushed tones that the latest Sex and the City was about to come on, thinking they couldn’t possibly get away with sneaking in the episode with present company. But then Zisblatt and her cohort flipped around enthusiastically. “They were like, ‘Wait a minute, we know about Sex and the City,’” says Beallor. And that’s how the group ended up enjoying an episode of Carrie’s “next thing” together.

This isn’t how I expected to start the conversation with the people behind a Holocaust documentary. But these moments of levity appear common with this group. They also feel necessary.

“You need it when the subject matter is so heavy,” says Moll, who joins Beallor, Zisblatt and the latter’s daughter Robin Mermelstein in the conversation on the occasion of The Last Days’ restoration and global streaming release.

The documentary focuses on the Hungarian Jews who were targeted by the Nazis during the final stages of the Holocaust. As the Nazis were losing the second world war, they redirected more resources towards completing their “Final Solution”. The film’s thesis is that the Nazis were so fueled by hatred that they would sacrifice their position in the war in order to carry out the genocide, deporting 438,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz within a six-week period. Survivors Zisblatt, Basch, Cahana, Firestone and the late Democratic politician Tom Lantos recount on camera their own ordeals from this period in horrifying and heartbreaking detail.

The Last Days was produced by the Shoah Foundation, founded by Spielberg in 1994 following the response to Schindler’s List, his monumental film about Oskar Schindler’s work to rescue Jews from concentration camps. When Schindler’s List won best picture at the Oscars, Spielberg made a plea in his acceptance speech. He asked educators to teach the Holocaust in schools and utilize the voices of the survivors, who until then were encouraged to put the trauma behind them.

“[Schindler’s List] was a catalyst,” says Beallor. She explains that in telling the story of the Holocaust, Spielberg built trust among survivors who felt they could finally open up about their experiences and be heard. As the founding executive directors of the Shoah Foundation, Beallor and Moll were tasked with collecting testimonies from more than 50,000 survivors who committed their stories to the digital archive for safekeeping.

“Once word got out that the Shoah Foundation existed,” Moll continues, “the phones were ringing off the hook with survivors wanting to tell their stories.”

Zisblatt was among those who gave testimony immediately after Schindler’s List’s release, though she says she has only seen “bits and pieces” of Spielberg’s film. “There are things that I just can’t handle,” she says from her Florida home.

Irene Zisblatt visits her grandparents’ grave with her daughter Robin. Photograph: Focus Features

Zisblatt was 13 years old when she arrived in Auschwitz in 1944. Before being separated from her family for ever, her mother gave Zisblatt four diamonds to hold on to until she could exchange them for bread. Because nowhere was safe, Zisblatt would swallow the diamonds, retrieve them from her own waste, clean them off and repeat that cycle. She describes that ordeal and more in The Last Days. In her book, The Fifth Diamond, she also writes about enduring Dr Josef Mengele’s experiments during her time in Auschwitz.

Zisblatt is wearing the four diamonds during the Zoom call. They’re housed in a pendant that hangs from her neck. She only wears the diamonds when educating about the Holocaust, which she does often. Zisblatt speaks at schools, colleges and on frequents trips to Poland for the March of the Living, an educational program that brings students from around the world to Auschwitz on Yom HaShoah, the Holocaust Remembrance Day.

She has published a version of The Fifth Diamond suitable for younger readers and developed a study guide to make it easier for educators to teach it to kids.

“I want them to feel proud of who they are, grateful for what they have and protect our future,” says Zisblatt, describing what motivates her. She says she has a meeting set up with four senators who are advocating to make Holocaust education mandatory in schools across the US. “Our generation had failed to find the tools to stop genocide. But [the next generation] have a chance to do that.”

A new generation will probably discover The Last Days, as it’s released in 33 languages on Netflix worldwide. Until now it has only been available on DVD.

“It’s going to be very interesting to see how the film plays for today’s audience,” says Moll, who has been trying to restore the film for years.

Beallor and Moll consider how the film will speak to the recent rise in antisemitism and xenophobia in the US, and the education people have been receiving about micro-aggressions and systemic racism from the #BlackLivesMatter movement. But I wonder how the film will speak to the crisis between Israelis and Palestinians.

On the morning we’re discussing The Last Days, the Guardian was reporting that eight children were killed by Israeli airstrikes on Gaza City. The war between the state and Hamas continues to escalate after Israeli forces began removing Palestinians from their homes in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood.

“There’s so many things going on in the world today that are born from hatred and fear,” says Moll. “The Holocaust definitely shows the dark side of what human beings are capable of.”

James Moll interviews Irene Zisblatt. Photograph: Focus Features

“I don’t like to be overly political,” Moll continues. “I don’t want to hit anybody over the head. I want people to hear these testimonies from the survivors, from Irene, make what they will of it and process it themselves. [I] don’t want to be prescriptive about that.”

Zisblatt volunteers a response. She returns to a moment depicted in The Last Days, when she and her daughter visit her old Hungarian village more than 50 years after the Holocaust. They meet with old neighbours and friends, some of whom worry that Zisblatt has returned to reclaim her family’s property, which they bought after the Holocaust. They’re defensive about their claim to land that Zisblatt wasn’t interested in.

Zisblatt reveals an upsetting detail that isn’t in the film. During that visit, one of her childhood friends looked at her family and remarked: “Hitler left enough of you to reproduce.” Moll and Beallor are hearing that exchange for the first time.

“I didn’t want to share that with you because I didn’t want the world to know that there is still so much hatred in my own town,” Zisblatt explains to the film-makers. “I didn’t want the world to see how much hatred is still going on, after all of this suffering.”

The Last Days is available on Netflix from 19 May