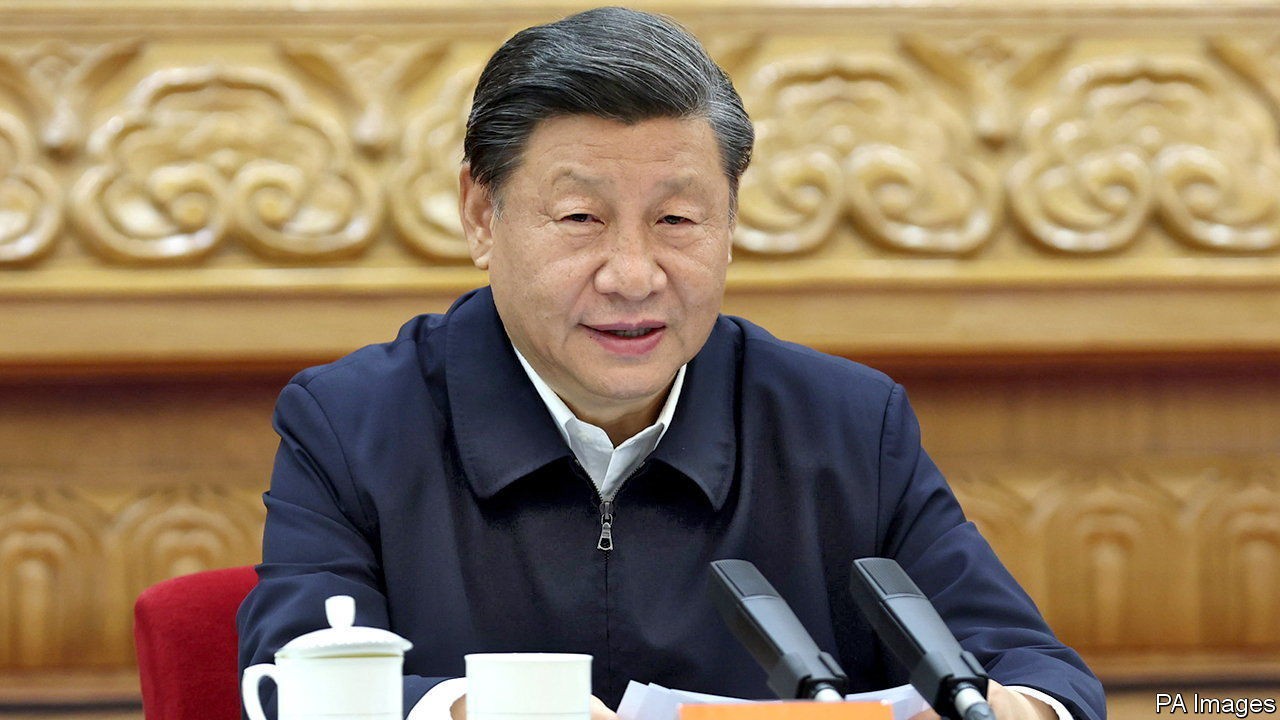

The crisis over Taiwan is yet another test for Xi Jinping

I T IS A case study in how not to manage expectations. As Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of America’s House of Representatives, mulled a trip to Taiwan, officials in China, which claims the island, warned her to stay away. “If she dares to go, just wait and see,” said a foreign-ministry official. The army “will not sit idly by”, threatened the defence ministry. President Xi Jinping suggested a furious reaction: “Those who play with fire will perish by it,” he told Joe Biden. The ultimatums sent Chinese nationalists into a frenzy. Many expected to see Ms Pelosi’s plane shot down if it approached Taiwan.

But her plane landed on the island without incident on August 2nd and Ms Pelosi spent the next 24 hours meeting with Taiwanese politicians and Chinese dissidents. Since she left on August 3rd, China has fired missiles over Taiwan (the first time it had done this), sent military ships and aircraft across the median line of the Taiwan Strait, and conducted large-scale drills in areas surrounding the island in what looked like a rehearsal for a blockade. It also imposed economic sanctions and suspended dialogue with America in several areas, such as military affairs. Still, many nationalists are not satisfied. Some joked bitterly that the neighbourhood committees enforcing covid-19 restrictions are fiercer than the foreign ministry: if the committees tell you to stay out of somewhere, you stay out.

The crisis has come at a particularly sensitive time for Mr Xi, just a few months before a Communist Party congress at which he is expected to secure a third term as leader, violating recent norms. This month, if tradition holds, party bigwigs and retired elders will meet in the resort town of Beidaihe, where in the past they have had informal discussions about policies and personnel. How much of that still goes on under the increasingly autocratic Mr Xi is an open question. But, whether or not it happens in Beidaihe, Mr Xi and other leaders must soon make some important decisions, on who will surround him at the top and what priorities to pursue in the years ahead—including on Taiwan, whose reunification with the mainland he has linked directly to his stated goal of “national rejuvenation” by 2049, the centenary of the Communist takeover of China.

Earlier in the year, amid a flurry of challenges, there was much speculation about the extent of opposition to Mr Xi within the top ranks of the party, and the impact it might have on his plans to remain in power. Then, as now, there was no convincing evidence that his plans could be disrupted. But Mr Xi cannot effectively govern without strong support from other powerbrokers, such as provincial party bosses and the armed forces, says Jude Blanchette of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a think-tank in Washington. “If everyone is upset, he can remain in power but he’s going to be fairly low on the throne and unable to really push through policy agendas.” The more beleaguered he looks, the more concessions he may have to make when it comes to choosing the party’s roughly 300-member Central Committee.

Mr Xi would certainly prefer that things were more stable. “China has been dealing with an extraordinarily difficult year, and much of the difficulty is a result of policy decisions that Xi himself has made,” says Mr Blanchette. The economy is slumping, in part due to Mr Xi’s zero-covid policy, which relies on mass testing and lockdowns to contain outbreaks. Sustaining that policy has become harder as new, more transmissible variants of covid emerge. People increasingly grumble about the government’s strict controls. Then there is Mr Xi’s support for Russia and its invasion of Ukraine, which has increased tension between China and the West.

Now add to that list the crisis over Taiwan. The challenge for Mr Xi is that he cannot appear weak, having projected an image of strength, asserted his personal authority over China’s armed forces and placed new emphasis on the goal of unifying Taiwan with the mainland. On the other hand, he cannot afford a full-blown military confrontation with America which would further destabilise the Chinese economy and, despite the growing strength of China’s armed forces, could still result in an American victory that would be devastating for Mr Xi and threaten the party’s grip on power.

Mr Xi has one big advantage in presiding over the world’s most extensive system of propaganda and censorship, which can suppress most criticism and amplify praise for his leadership. The party has long exploited nationalist sentiment by stirring it up in times of crisis to rally public support and then tamping it down when it threatens to spiral out of control. It can also portray its actions differently to domestic and international audiences. Already there are signs that the government is trying to address the perception that China’s response so far has not been sufficiently robust.

“Our countermeasures will be very strong, effective and resolute,” said Hua Chunying, a spokeswoman for the foreign ministry, on August 3rd. America and Taiwan “will feel their effects gradually and continuously”, she added. Some nationalists have also tried to reset expectations. Sima Nan, with nearly 3m followers on Weibo, urged his followers to be patient and store up their anger. “When shall we eat this piece of meat?” he wrote of Taiwan. “I think it will certainly be slowly.”

If Mr Xi can get the balance right in calibrating China’s response in the coming months, he may yet emerge stronger from the crisis, bolstering his chances of promoting allies to important positions in the new leadership after the party congress and reinforcing his self-styled image as the strong leader China needs to confront America and take its rightful place as a great world power.

But Mr Xi may simply be storing up problems for the future by raising expectations of Taiwan’s eventual reunification with the mainland. Fed on a diet of “Wolf Warrior” films and other militaristic propaganda, Chinese nationalists have an increasingly unrealistic sense of foreign policy. Mr Xi, for his part, says the Taiwan question cannot be passed down to future generations indefinitely. Yet his response to Ms Pelosi’s visit is almost certain to alienate the island’s population further and galvanise support for it from America and its allies, making peaceful reunification an ever more distant prospect. ■