Chinese leadership and the coming government

Theoretically, the members are chosen by delegates to the national party congress to represent the rich and diverse voices of the 90 million party members. While the members are ranked by a hierarchical order, they carry the same voting rights and make decisions collectively, with the party secretary as first among equals.

And they vote to decide on most key issues. For this reason, the size of the standing committee is almost always kept at an odd number to ensure there are no tied votes.

In practice, the standing committee is effectively “the small council” to help the party chief rule the country and the party. Each member is given certain portfolios and areas of responsibility. The exact division of labour and chemistry among the standing committee members varies greatly, and some party secretaries are more dominant than others.

During Deng Xiaoping’s era, when the real power was in the hands of the party elders, there were mostly just five standing committee members. Deng’s eventual successor Jiang Zemin expanded the standing committee to seven in 1992, and again in 2002 as he stepped down from the party leadership role.

Hu Jintao, whose tenure was marked by a diffusion of power, had eight other colleagues. While the extra seats ensured different factions had a voice in the top decision-making body, it also led to fragmentation.

During Hu’s decade, the standing committee was often half-jokingly called “nine dragons ruling the rainfall” – a Chinese idiom based on the mythical creature’s role in controlling the rain. Too many dragons lead to severe droughts, as none is powerful enough to produce a downpour.

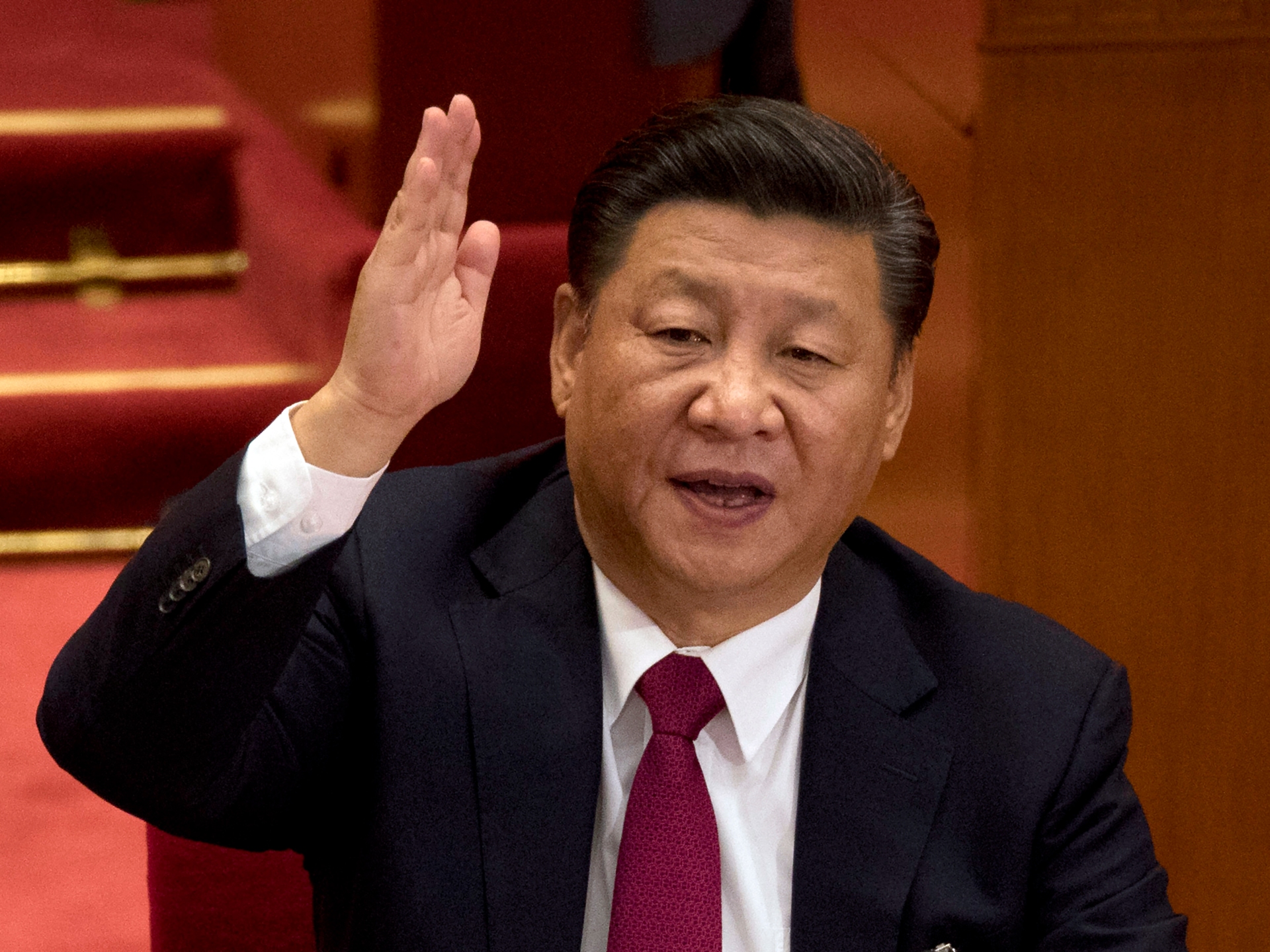

When Xi Jinping took over in 2012 with a mission to revitalise the party, he reduced the standing committee back to seven. It was seen as a step to concentrate power for the most powerful leader since Mao Zedong and Deng.

Most of the analysts interviewed by the South China Morning Post believe this was the right balance between representation and efficiency.

Xi, 69, leads the current Politburo Standing Committee. The others are, by hierarchical order, Premier Li Keqiang, 67; Li Zhanshu, 72, head of the top legislative body; Wang Yang, 67, chairman of the top political advisory body; ideology tsar Wang Huning, 67; Zhao Leji, 65, head of the top anti-corruption body; and Vice-Premier Han Zheng, 68.

Xi is widely expected to secure a third term in congress. One of the earliest and surest indications was the 2018 amendment to China’s constitution removing term limits on the presidency.

Although the presidency and party chief are different roles, they are usually occupied by the same person. Removing the term limits for the presidency strongly suggested that Xi would stay for more than two terms.

It is, however, unclear whether other Politburo Standing Committee members aged 68 or over will have to retire, as has been the case in the past.

If the convention holds, Li Zhanshu and Han Zheng will step down.

Li Keqiang, 67, must step down as premier after completing his second term. He may stay in the standing committee and pick up another official position, although most analysts believe a full retirement is more likely.

This raises the question for Wang Yang and Wang Huning – both also 67.

Analysts are divided over how the leadership change will pan out, with estimates of how many seats could be vacated ranging from one to five.

There are plenty of hopefuls waiting in the wings to take them.

They include Chen Miner, Ding Xuexiang, Hu Chunhua, Chen Quanguo, Cai Qi, Li Hongzhong, Li Xi, Huang Kunming and Li Qiang – all currently either party secretaries of provinces or municipalities or heads of key party organs.

But many analysts say the size of the Politburo Standing Committee is unlikely to change, given that Xi has already consolidated his hold on power.

“Historically, the committee had three to five members when the overriding need was power centralisation,” said Chen Daoyin, a political scientist and former professor at the Shanghai University of Political Science and Law.

“When the emphasis was on balancing power, the [committee] usually expanded to have more members. In the Xi era, power centralisation is the main theme, which means the possibility of the committee expanding is low,” Chen said.

“Meanwhile, Xi has already cemented his power, so there’s no need to reduce the number of seats.”

The Politburo Standing Committee has not always been the party’s supreme body. It was given exclusive decision-making power in 1992, when then paramount leader Deng disbanded the Central Advisory Commission – a body made up of influential, retired party elders that had previously had the final say on key decisions. However, some retired elders have remained influential within the party.

Xi has become the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao and Deng, helped by a widespread crackdown on corruption within the party, government and military, and indoctrination in his political ideology, Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.

The propaganda machine has gone into overdrive in the run-up to the party congress, including embracing a new slogan to entrench Xi’s status – the “two establishments”. It refers to establishing Xi’s status as China’s “core” leader and establishing his political doctrine, which was enshrined in the constitution in 2018.

Chen said a big change to the size of the Politburo Standing Committee, say an expansion to nine or a reduction to five, would be telling.

“Both are extreme scenarios and would suggest Xi’s authority was impaired, there was an unexpected objection or an internal power struggle among Xi’s protégés,” he said.

Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, also expected the standing committee to be kept at seven.

“The committee size used to be expanded when the general secretary needed to accommodate colleagues from different factions and there was just not enough scope to do so with a lower number,” he said.

According to Tsang, Xi should have no need to pacify the factions by increasing the committee, with many of their key players weakened after a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that targeted high-profile figures and others, right down to the grass roots.

Five years ago, Xi told party leaders that five disgraced heavyweights – Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, Guo Boxiong, Xu Caihou and Ling Jihua – had “all engaged in political conspiracy activities”, according to a copy of the speech published by Xinhua.

Zhou had been a Politburo Standing Committee member, while the other four were either on the Politburo or the Central Secretariat, the party’s nerve centre.

Former deputy public security ministers Fu Zhenghua and Sun Lijun are among the more recent targets, both accused of political disloyalty, establishing political factions, and forming groups for personal gain.

Neil Thomas, a China and Northeast Asia analyst with consultancy Eurasia Group, also said Xi was unlikely to change the size of the standing committee at this year’s congress.

“An increase would make central decision-making more unwieldy and a decrease would deny expected promotions to his allies,” he said. “Xi does not need to change the size of the Politburo Standing Committee to consolidate his power, so there seems little incentive for him to spend political capital on doing so.”