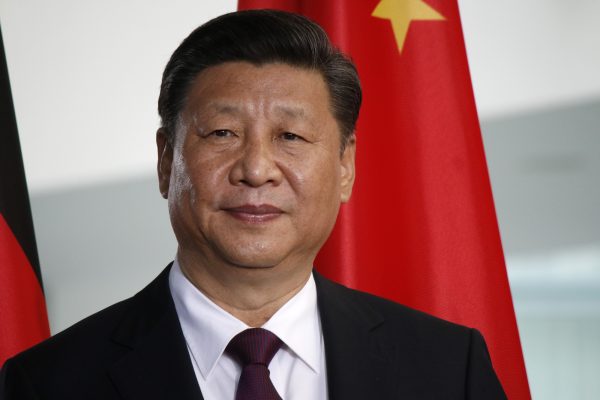

Xi Jinping’s Great Leap

The world took note in late November when Chinese citizens braved prison to protest their government’s restrictive “Dynamic Zero” COVID-19 policies. In a system honed to suppress dissent, their challenge to the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party and paramount leader Xi Jinping himself was unprecedented. In early December, after the protests had ceased or were put down, the Chinese government removed COVID-19 restrictions it had maintained over the past three years while arbitrarily downgrading the virus’ threat.

While these events may seem like just two more pieces in a cycle of public dissatisfaction and government reaction, in fact they represent an historic turning point. Despite their government’s insistence on costly restrictions for the past three years, China’s citizens face what could become their country’s largest mass-death event since the Great Leap Forward. Worse, while the crisis rages, their government seems unable or unwilling to help. Xi’s only apparent contribution to these momentous events has been a few platitudes in his New Year’s address.

This devastation will create lasting cognitive dissonance in the minds of Chinese citizens, challenging Xi’s ability to govern. For the world, this failure threatens new waves of COVID-19. It also raises profound questions about the deference international authorities and investors have shown to Beijing in light of its increasingly malign policies. On both practical and moral grounds, the world must insist that China uphold some level of cooperation on public health, among other international norms.

Beijing in Crisis

Diplomat Brief Weekly Newsletter N Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific. Get the Newsletter

As I’ve written previously, the CCP-dominated government’s priority during the COVID-19 crisis has been to protect its legitimacy, even at the expense of public health. Examples include spreading misinformation and disinformation, as well as withholding information. Internationally, Beijing’s exclusion of Taiwan from the World Health Organization has endangered the health of nearly 24 million Taiwanese (which the PRC claims as its own citizens). Politics is in command of China’s health policy, not public well-being.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

COVID-19’s threat to China and perceptions of the government’s negligence in stopping its initial spread presented serious challenges to CCP legitimacy. Xi’s answer in 2020 was to invest even more heavily in the authoritarian tools he had used to consolidate his power, preventing the spread of COVID-19 by physically isolating his population. China also built out hospital space, hoarded protective equipment, and emphasized testing, a relatively effective measure early in the pandemic before vaccines became available. These measures exacted a high price in public expenditure and individual loss of freedom, but they did buy time for China to vaccinate its population and prepare for a “new normal.”

Moreover, Beijing’s propagandists took China’s ability to weather the storm as license to boast about the superiority of authoritarian governance and level spurious attacks on the quality of governance in democratic or “Western” nations. Throughout the crisis, their message has been unanimous: one of “decisive victory” through Xi’s direct leadership and Chinese sacrifice.

But Xi never followed up on this apparent success. He failed to deal with the elderly Chinese population’s high vaccine refusal rate, stock lifesaving medicines in preparation for reopening, or formulate a plan to mitigate the inevitable COVID-19 spike after reopening. Notably, he refused to allow more effective mRNA vaccines into China without manufacturers giving up their intellectual property, leaving the Chinese people more vulnerable.

How vulnerable might they be? Given the lack of verifiable statistics, any estimate is questionable, but Hong Kong offers a point of comparison. For most of the pandemic, the Special Administrative Region had kept its loss of life to a minimum: officially 213 people, a small fraction of its population of 7.5 million. With the Omicron outbreak last spring, however, Hong Kong lost 9,300 lives, bringing its death toll up to 0.1 percent of the total population. Were China’s reported population of 1.4 billion to experience a proportionally similar loss, that would mean some 1.8 million deaths.

This parallels predictions from The Economist, although there seems to be a point of analysis missing: While vaccination rates may be similar, Hong Kong’s medical capacity surpasses its mainland counterpart. Looking at the question another way, should mainland China experience 800 million infections – high but still conceivable – with an infection fatality rate of 0.68 percent, that would mean over 5.4 million deaths. Reports of a large death toll are already beginning to emerge, straining the government’s ability to suppress the unfavorable news.

Echoes of the Past

Xi’s continued refusal of aid in the face of such a threat hearkens back to Mao’s rejection of food aid during the height of his Great Leap famine. Between 1958 and 1961, Mao’s mad dash to collectivize and industrialize China spent the energies and material resources of the Chinese nation while impoverishing the individual citizen. For example, peasants were forced to melt down their metal implements to increase China’s steel production. The industrial and agricultural results were abject waste, but the human toll was worse: 20 million or more killed by famine (perhaps 3.1 percent of the population at the time).

Worse still was the cause. Despite bad harvests, China at the time probably had enough food to prevent widespread starvation, but in order to show a grain surplus to justify Mao’s policies, the government withheld that food from the Chinese people, starving tens of millions to death. In the midst of the chaos and tragedy, the Chinese authorities decided to withhold statistics. In an ominous parallel, Xi’s government today has essentially given up on providing COVID-19 statistics.

The Chinese people’s capacity to “eat bitterness” has its limits, and Xi’s early success has proven unsustainable. Mao’s government was able to sweep its famine under the carpet, but China’s population today has been exposed to the broader world. Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening has improved Chinese citizens’ economic well being immensely. In other words, the standards have changed.

Seeing the world opening up while even China’s wealthiest cities experience food insecurity due to government lockdowns proved too much. The population could no longer “restrain the soul’s desire for freedom.” Defying their government’s massive security apparatus, they took to the streets in November to demand change. Mao’s chaotic campaigns never met with this level of resistance and, until now, neither had Xi’s.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Several factors suggest this represents a serious policy setback for Xi: the stridency of protesters in the face of jail time, their targeting of Xi and the CCP directly, the suddenness of the government’s policy turnaround, and the seeming willingness of CCP officials to work without Xi’s endorsement. Extreme isolation was always a difficult pill to swallow and whatever utility it had in 2020 had long since evaporated by 2022.

Regardless, Xi had continued to insist on zero COVID through to the Party Congress in October. For example, former Shanghai Party Secretary Li Qiang enforced a months-long lockdown in the spring, causing many residents of China’s wealthiest city to starve. To the surprise of some, Xi elevated Li at the Congress to a top Politburo Standing Committee position, demonstrating the “correctness” of zero COVID, whatever the cost.

China watcher Bill Bishop believes Xi delayed China’s COVID-19 reopening to ensure that the health crisis we are witnessing now would not affect Xi’s prospects at the Party Congress. There were rumors of reopening at the beginning of November (shortly after the Congress), even as various cities began reporting outbreaks. Although these outbreaks called into question the policies Xi had just touted at the Congress, the government still held firm to zero COVID. By the end of November, however, in the face of a progressively more infectious virus and an increasingly open world, something changed. Xi’s policy of isolation broke down. Facing a restless public and, importantly, pressure from Chinese industry, China’s government appeared to open the floodgates for COVID-19 to spread.

A Xinhua editorial on December 5 announced this new era, proclaiming that Omicron was less deadly and China’s vaccination program and experience had created a “new situation.” Overnight, “zero COVID” disappeared from official parlance as localities dropped testing requirements, authorities granted emergency approval to new vaccines (December 6), industrial giants announced the termination of the nation-wide travel restriction app (December 12), and a former health official promised a downgrade to the threat level of COVID-19 (December 15).

For any other policy, having experts float ideas would be unremarkable. But releasing a spate of critical policy changes without Xi’s imprimatur in the midst of a national emergency is surprising. It wasn’t until January 1 that Xi emerged to give his customary New Year’s speech. The emerging COVID-19 outbreak played little role in his remarks besides references to a “new phase,” a “time of hard work,” and “glimmers of hope.”

Had Xi planned all along to wait until after the Congress to ditch zero COVID? If so, one would have expected a more orderly process, with Xi in command and claiming victory, as he has done all along. What we see looks more like hasty policy decisions – possibly not made by the central government – coming in response to resistance. Meanwhile, Xi has remained on the sidelines, and it is not clear there is any overall program. This suggests that Xi is either laying low to avoid responsibility until the worst passes or is unable to make policy and has left his nation rudderless in a storm.

With no outright cure for COVID-19 in the offing, a spike in deaths was practically inevitable and is not entirely Xi’s fault. However, the failure to prepare clearly is. Not since the bizarre purported treason of Mao’s anointed successor Lin Biao in 1971 has the Chinese public been faced with such clear and vexing evidence of a deficient paramount leader. Considering Xi’s tight control over his nation’s security apparatus, even this setback might by itself be survivable for him, although his ability to set policy would be at least temporarily impaired.

More seriously, Xi must account to the Chinese people for the years of their lives he has used up in pursuit of his suddenly-defunct policy, a vast cost in freedom and economic development which in retrospect he has wasted. In that light, his New Year’s admonition to “live up to the times, don’t squander your youth” (不负时代,不负华年) must be galling indeed.

There comes a point at which no security apparatus can stifle dissent. As the magnitude of this tragedy and perceptions of Xi’s culpability mount, the odds of some form of regime change increase.

The Way Ahead

Notable in this crisis is the CCP leadership’s indifference toward global health concerns, beginning with its initial coverup and culminating in its lack of preparation and sudden elimination of control. China’s COVID-19 concealment policies recently inspired this joke about a woman calling home to tell her mother that her whole family had tested positive. Her mother was shocked and said: “The news reported four cases in Guangxi today. How could they all be at your house?”

What local statistics that do emerge, apparently untethered from national control, are painting a grim picture. But the tragedy may not be China’s alone, as the surge in cases could potentially create new outbreaks and highly infectious variants. Hopefully, other countries’ facilities and preparation are adequate to deal with the crisis, but this does not remove the onus on China to act responsibly.

Against this background, the WHO has downplayed the malign aspects of Beijing’s response, even praising the lengths to which it has gone to limit the spread of the virus. Executive director Dr. Michael Ryan continued to defend China on December 14, 2021, saying:

There’s a narrative at the moment that China lifted the restrictions and all of a sudden the disease is out of control… The disease was spreading intensively because I believe the control measures in themselves were not stopping the disease. And I believe China decided strategically that was not the best option anymore.

In light of China’s precipitous abandonment of controls, the idea that China decided this “strategically” seems questionable. Moreover, Ryan’s defense of a malign actor strains the WHO’s credibility.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

As for whether this crisis might precipitate the removal of Xi or the CCP, the attitude of most China watchers in general has been to assume their power remains entrenched. Bill Bishop notes that “from the outside at least, [Xi is] in [an] extremely secure political position.” Despite this baseline assumption, Minxin Pei adds a note of caution, saying Xi “must realize that a renewed compact with the Chinese people may be essential to preserving his own ‘mandate of heaven.’” Even Bishop believes Xi has “massively exceeded” his mandate.

We should remember that the CCP is no stranger to regime change: a military coup enabled Deng’s ascent and subsequent evisceration of Mao’s programs. Unfortunately, the Chinese people had to wait until after Mao’s death to taste that bit of freedom. But Xi is no Mao. To be sure, he wields power quite effectively within the CCP, but were his policies as successful as his crackdowns, he would already have secured his place among the pantheon of CCP leaders alongside Mao and Deng. Rigid insistence on party discipline and a cult of personality do not breed the habits of mind that allow a system to adapt and thrive. Xi’s accomplishments are proving to be pyrrhic victories. He believes he must persist to save the CCP, but doing so is killing his country.

One area to watch for signs of rationality is whether China accepts mRNA vaccines. Allowing their entry now may not affect the current wave of death, but could be a way to mitigate future waves. This would be an admission of error, but that could hardly be worse than simply allowing citizens to die. Returning to an orderly opening strategy and securing needed hospital space and medicines also seem like urgent priorities. But that seems to be the problem: With Xi’s excessive policies on ice, China has yet to return to any program whatsoever, simply leaving the population to its own devices.

Since the national government’s entire history and image are built on protecting the Chinese people, the cognitive dissonance of this desertion may prove too great to bear. The people today will not suffer repeated disasters to “perpetuate the worship and sustain the tyranny of one abominable creature.” Should the loss of life and waste of resources prove too great and should local cadres find themselves abandoned, they may defect from Xi (although probably not the CCP). If he is then unable to mobilize the security services against them, this would constitute a coup against the standing order.

Democratic and likeminded nations must take a lesson from this crisis and act to protect their publics. As the United States recently won important concessions by insisting that China’s companies adhere to accounting standards, so should governments insist on compliance from Beijing in global health and other critical areas. This means China must share its knowledge of COVID-19 openly and allow an investigation of its origins, not punish nations that simply request this. Governments should encourage investors and industries to look for business opportunities among allies and partners, not in a country engaged in slave labor. Only by increasing pressure to act responsibly can the world hope to have any influence on China.