The Security Law in Hong Kong May Hurt the City’s Reputation as a Financial Center

Paul Chan, the top finance official of Hong Kong, traveled to Paris, London, Frankfurt and Berlin last September to lure foreign investors. Last month he abolished taxes on foreigners’ purchases of Hong Kong real estate. And he is soon set to host an international art show, as well as conferences for big money funds and advisers to wealthy families.

Mr. Chan’s brisk work pace represents an attempt to shore up Hong Kong’s role and image as the financial hub of Asia. But that effort is now colliding with a move by the city’s Beijing-appointed leaders to further tighten their crackdown on the remaining political freedoms in the city.

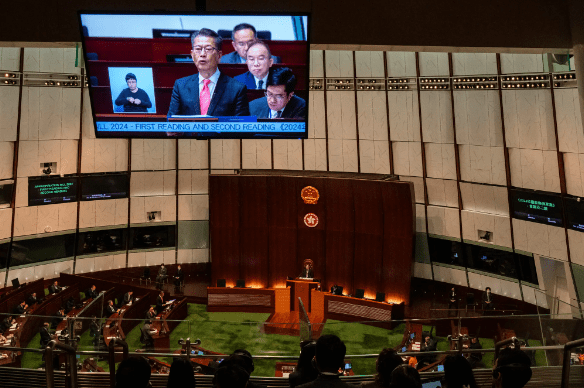

Hong Kong’s legislature approved broadly worded security legislation on Tuesday. City leaders described the law as necessary to stop foreign interference in local politics, but critics characterized it as a comprehensive effort to muzzle dissent.

Under its top leader, Xi Jinping, China has asserted greater influence in the past four years over Hong Kong’s laws and prosecutors. That has raised alarms for American and European companies that use the city and its open financial markets as a gateway to China. The mainland’s own economic struggles, especially in real estate, have further shaken confidence in Hong Kong as a place to put money.

Many investors and companies have already begun moving activities to Singapore, a rival that has the advantage of being an independent country 1,200 miles southwest of China.

“The new national security rules have eroded Hong Kong’s distinctiveness for foreign firms and Chinese exporters — its comparative advantage is less clear than it once was for many businesses,” said Mark Wu, the director of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

Shiu Sin-por, a former head of the Hong Kong government’s policy review agency who is now a senior adviser to Beijing on Hong Kong issues, said the legislation would not have a practical effect on trade or financial markets. “It might create an image problem, but it would not make any difference for ordinary investors,” he said.

The clampdown coincides with an already difficult time for the Hong Kong economy and its financial sector. Its close links to the mainland economy have been the city’s greatest strength — and now have become a liability as China’s economic activity slows. The city’s stock market has lost nearly half its value in three years. Dozens of mainland real estate developers have defaulted on bonds issued in Hong Kong, inflicting billions of dollars in losses on investment funds in the city and damaging the image of its bond market.

To make matters worse, interest rates have soared in Hong Kong, roughly in line with those in the United States. That is because the city’s currency is tightly pegged to the dollar and fully convertible into dollars — a monetary policy that is central to the city’s role as a global financial center. But high interest rates have hurt the city’s huge real estate sector.

Hong Kong imposed lengthy quarantines during the pandemic, eroding its role as an air travel hub. Mainland Chinese cities like nearby Shenzhen have built extensive, ultramodern container ports, erasing Hong Kong’s leadership in logistics.

Beijing has also introduced extensive duty-free shopping on China’s Hainan Island. That has eliminated much of the need for mainland shoppers to cross the border to Hong Kong to avoid the mainland’s combination of steep taxes on imports and high sales taxes.

Banks and consulting firms have already begun moving staff to Singapore for politically sensitive activities, like assessing the performance of the mainland Chinese economy. Hong Kong’s new law also poses a further challenge for the city’s once vibrant media sector, which now faces the threat of prosecution for sedition for criticisms of the government.

Hong Kong was a British territory from 1842 to 1997, when London returned it to mainland China’s control. The city retains a legal system based on Britain’s common law system.

Many mainland Chinese companies continue to sign contracts under Hong Kong law. The city’s courts are perceived as free from political interference on commercial issues, although critics warn that the Hong Kong government now appoints pro-Beijing judges.

Hong Kong’s legal code since 1997, known as the Basic Law, requires the city to pass legislation against sedition, secession, treason, subversion and theft of state secrets, as well as to prohibit foreign political organizations from conducting political activities in Hong Kong. The city’s leaders tried to pass the legislation in 2003 but backed off after a huge street protest. Beijing then imposed its own national security legislation in 2020 after a wave of protests the preceding year.

Regina Ip, a leading member of Hong Kong’s cabinet, said the new law would allow leaders to focus on the economy. “We are 26 years late, and more importantly, we need to focus on boosting the economy in the next phase of our development,” she said.

Mrs. Ip’s point was echoed by Leung Chun-ying, a senior adviser to Beijing leaders and former Hong Kong chief executive, the top governmental role. “It is time for Hong Kong, not Beijing, to enact,” he said.

International criticism of the new law has been broad and fierce.

“It could lead to significant constraints on freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, the right to dissent,” said Nicholas Burns, the United States ambassador to China.

Hong Kong leaders contended that the law was portrayed as more drastic than it really is. They said that what Hong Kong was doing to limit foreign interference was less extensive than recent efforts by countries like Singapore and Australia, two of the main destinations to which many companies and investors are moving.

Hong Kong’s law allows a broad role for the judiciary to review government decisions on national security cases, Mr. Leung said in an interview in Beijing.

Businesspeople in Hong Kong say many of the activities prohibited by the new legislation could already be deemed illegal in some form under Beijing’s legislation in 2020. So they are watching to see how the new law is implemented.

“It is fair to say that most of the changes are already baked in,” said Steve Vickers, the chief executive of Steve Vickers and Associates, a regional corporate risk consulting firm in Hong Kong.