Tibet, the region that is home to the Chinese Communist Party

The white and reddish walls of the Potala Palace, the Dalai Lama’s former residence, rise on the hill opposite. It has something of an ancient ship about it, like a stranded ark awaiting the flood, riddled with dozens of hatches. Tibetan fabrics flutter above the galleries. The view is lost in the labyrinth of staircases that crisscross toward the sky in an optical illusion crowned by golden roofs. A blinding sun beats down at an altitude of 3,646 meters. It is midday in Lhasa, the capital of the autonomous region of Tibet, on the borders of China, at the foot of the Himalayas. The current Dalai Lama left this city in March 1959 on his way to exile. He has never returned to what he considers an “occupied” territory.

Down here, in the square at the foot of the palace, a ceremony has just been held to commemorate the other side of that milestone. Soldiers have raised the flag of the People’s Republic and a floral frieze has been laid out with the inscription: “March 28, Day of the Liberated Serfs of Tibet.” Tourists from all over China stroll by. And two huge billboards on the sides emphasize that everything remains under Beijing’s control. One displays the faces of the five great leaders since 1949, from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping. The other is reserved for the latter. It is a face of Xi, about 10 by 6 meters. It is reminiscent of Mao’s at Tiananmen Square; his eyes survey every corner of the space.

The Chinese Communist Party is omnipresent in Tibet. Its traces are visible throughout a five-day visit organized by the State Council (the Chinese government) for various media outlets, including EL PAÍS.

“The Party’s radiant light illuminates the borders, and the border people have their hearts turned to the Party!” reads a billboard by the roadside. There are dozens of similar messages, scattered here and there. Going hand in hand with the authorities is the only way for foreign journalists and observers to enter the region. It is sensitive territory. There have been outbreaks of rage here in the past, dozens of Tibetans have set themselves on fire, and the repression has been denounced by governments, NGOs, and international organizations. The self-immolations have long since ceased to make the news; criticism persists. “Since 2013, the human rights situation of ethnic Tibetans in Tibetan areas of China […] has been deteriorating,” the European Union delegation to China stated in December. In March, the United States sanctioned Chinese officials for failing to provide unrestricted access to journalists, diplomats, and independent observers.

Much of the concern centers on the erasure of Tibetan identity and culture. In 2023, the UN expressed concern about the separation of one million Tibetan children from their families for “forced” assimilation in boarding schools. Beijing claims that this network of schools is open to everyone, and a visit to one of them will be included in the program.

The trip aims to showcase businesses, social services, infrastructure, and tourist attractions. The focus is on development, investment, and opportunities for locals. The agenda has been organized so the media can see what Beijing wants to show. Everything is focused on highlighting the “unity” between Tibet and China: from the hotel (with a huge Chinese flag dominating the lobby) to the evening show (an embellished tale about the 7th-century Chinese princess Wencheng, who married the Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo). It fits with Beijing’s message: “It is the most powerful historical foundation of our national unity,” summarizes one of the show’s organizers.

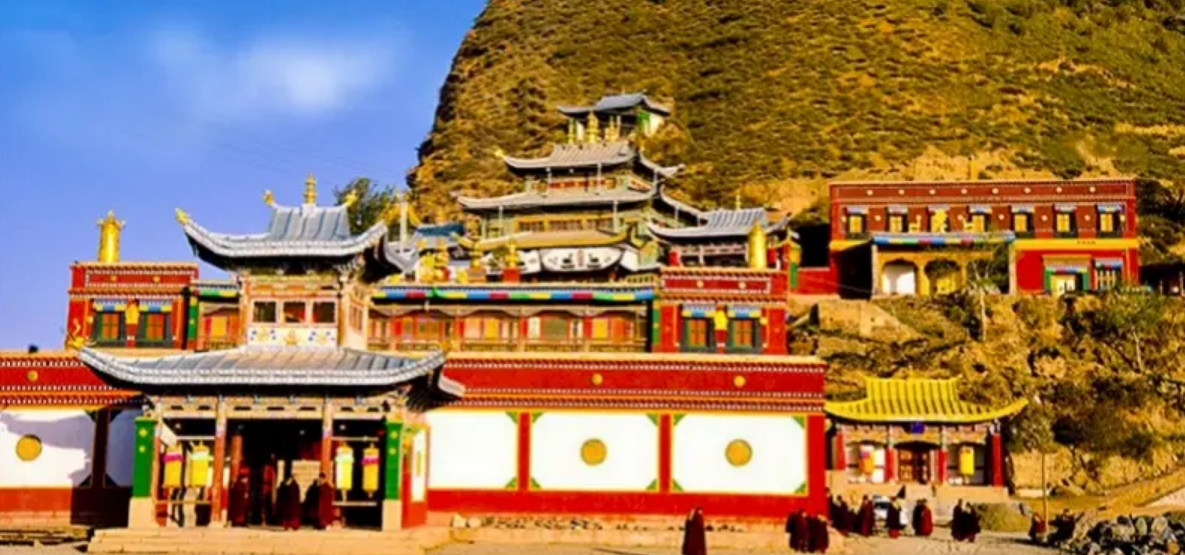

At Jokhang Monastery, a spectacular 7th-century complex in central Lhasa, the holiest monastery in Tibetan Buddhism, the religious realignment with Beijing is also clear. The Ba, a monk draped in a maroon robe and deputy executive director of the center’s management committee, does not shy away from the latest controversy surrounding the Dalai Lama, whose image is banned in Tibet, but who remains the spiritual leader of the religion. At 89 years old, the Dalai Lama has stated that in his next reincarnation, he will be born in the “free world.” The Ba responds: the choice will follow “historical rituals” and, in any case, “must be recognized by the central government.”

In a day care center for seniors, there’s a picture of the Chinese president at the entrance. Another photograph of the leader presides over the lounge where elderly men with tanned faces and Tibetan hats play dice and sip tea. They are retired farmers. They speak Tibetan. They are over 70. One says that the region has undergone “a dramatic change,” according to the translation provided by the government. He speaks of the bridges and roads that “now lead everywhere,” of the plumbing and hygiene compared to the filth of the past. Their children no longer work in the fields; they have bought trucks and are engaged in construction. Some were born before the arrival of Mao’s troops, when the Dalai Lama was still in power.