China can open doors for Central Asia

Growing disaffection with Russia among the former Soviet republics of Central Asia is providing China with an opportunity to further its economic and political interests in the region, according to a panel held by an American think tank earlier this week.

Long considered part of Russia’s sphere of influence, the war in Ukraine – also once a Soviet republic – has increased reservations among the region’s governments, leading them to look elsewhere for cooperation, according to an online panel discussion held on Wednesday by the Washington-based Atlantic Council.

“There are many small indicators that Russia may not be enjoying the former hegemonic power they once did,” said Ariel Cohen, a non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Centre.

Cohen said regional governments have grown wary of an increasingly assertive Russia and what he called the “Putin Doctrine”, or the belief that the existence of Russian diaspora or shared culture and history provide justification for military intervention.

This is providing China with an opening to further grow its footprint in the region, the panel heard.

“With Russia likely to recede significantly from Central Asia in the near future, it does open doors for China to come in,” said Bruce Pannier, a freelance journalist and analyst who has covered Central Asia for decades and was invited to speak on the panel.

China has in recent years sent strong signals it seeks further economic involvement in the region.

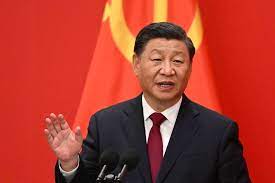

As part of his first trip abroad since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, President Xi Jinping visited Uzbekistan for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in September.

During the summit, China signed over 30 two-way agreements across various sectors with the region’s governments, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Central Asia is also a key corridor in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which has brought major infrastructure projects to the region by way of railways, highways and power stations to the largely underdeveloped region.

Central Asia is also a strategic route for natural gas, something the countries in the region are looking to export more of, and China wants to reach its decarbonisation goals.

“China wants to increase the role of natural gas in the energy mix,” said Erica Downs, a senior research scholar with Columbia University’s Centre on Global Energy Policy.

“This is good news for [Central Asian] countries looking to export natural gas to China.”

Natural gas – which is considered the cleanest of the fossil fuels – makes up around 9 per cent of China’s energy mix, but it is hoping to increase that share to 15 per cent by 2030 when it plans to reach peak carbon emissions, according to China’s state planner, the National Development and Reform Commission.

Central Asia was responsible for around 25 per cent of China’s total natural gas imports in 2021, according to Chinese customs data, and that is expected to increase significantly in the years to come.

New extensions have been revealed for the US$7.3 billion Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline, which will increase the share of natural gas supplied to China. It could feasibly double the amount supplied to China from Turkmenistan, which is China’s largest supplier of natural gas.

“It is creating a new strategic energy channel for cooperation between China and Central Asia countries,” Downs added.

However, even as Russian influence wanes, Pannier said countries in Central Asia are not interested in depending on China for all of their needs.

“They’ve been under ‘big brother’ Russia for a long time,” he said. “They don’t want to see that replaced by the same essential relationship but this time with China.”

China has come in for criticism from the West for not condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while also maintaining trade ties.

In October, China’s import from Russia surged by 36 per cent to nearly US$10.2 billion, while exports rose by 34.6 per cent to almost US$7.4 billion. Also in September, the volume of liquefied natural gas imported from Russia rose to 819,344.4 tonnes, valued at US$1.03 trillion, both record highs, according to Chinese customs data. Pipeline natural gas imported from Russia in September was valued at US$411.4 million, which was also a record high