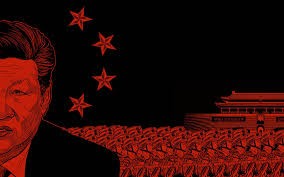

The risk of trading with China

Many metrics indicate that China is now the largest economy in the world. China even claims that its economy is stronger than ever, and growing after recovering from the damage done by the pandemic as the rest of the world continues to battle the Chinese-origin virus. The unique authoritarian brand of capitalism practiced by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has allowed the country to become the largest trading nation in the world. As a prime exporter to over a hundred countries with an overwhelming positive trade balance with most — barring a few countries such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Brazil — the Red Dragon’s asymmetrical trade relationships leave its trading counterparts vulnerable to its exploitative use of financial clout.

A particular abuse of this dynamic manifests in increased risk importers find in selling their goods to the Chinese market — China erects excessive market access barriers that discourage foreign firms from importing goods to the former; and smaller firms bear the brunt of these disproportionate and often contradictory complex bureaucratic obstacles.

This state of affairs is exacerbated by the fact that China’s recent plan to shift the economy into a service-based one from manufacturing had brought with it unfavourable growth rates. The introduction of new laws and regulations, and the CCP’s covert plans to execute said policies — under an ambiguous timeline — increase the risk of entry to an unreasonable degree; although the Chinese economy is booming in the aftermath of tackling COVID-19.

With already arduous and confusing bureaucratic processes that insulate the Chinese market, importing goods to China is not only difficult but a potential hazard. The United State’s International Trade Administration cites a myriad of barriers to doing business in China — “inconsistent regulatory interpretation and unclear laws” being the primary source of concern. Furthermore, increasing labour costs, licensing, protectionist policy, corruption, taxation, and disregard for intellectual property rights are factors that contribute to a climate that deters economies from entering the Chinese market — thus accentuating China’s economic leverage.

China claims it has reduced import-export duties — i.e. value-added tax consumption tax, and customs duties — for the purpose of encouraging domestic consumption, an effort made critical with its ongoing US trade war. Yet, in trading with India, their response has been antagonistic, to say the least. While it is true that India accounts for a small share of its exports, it seemingly justifies China’s illicit export and import practices. India’s imposition of tariffs to counteract the imbalance has been met with passive-aggressive hostility.

Not until 2 years ago, India was barred from exporting rice other than of the Basmati variety to China. Nevertheless, India has had a stronghold on the African market with respect to non-Basmati rice. Now, China has begun exporting non-Basmati rice at USD 300 to USD 320 per tonne; India sells the same at around USD 400 per tonne. India’s export of non-Basmati rice has fallen considerably from FY 2018-19, falling from INR 14000 crore to INR 9000 crore in one financial year. Such bad-faith tactics constrain the Indian economy’s growth yet the CCP expects India to abide by its disproportionate trading standards.

Nevertheless, China’s early recovery from COVID-19 has caused imports to spike — as with other economies that have been able to control the pandemic. Even amid the ‘Boycott China’ movement in India, inward trade with India has not curtailed. In fact, exports from India have seen a 78% on-year increase. Industrial commodities such as organic chemicals, ores, iron, and steel have been at the forefront of this phenomenon. Meanwhile, Chinese goods suffer in India due to stricter import restrictions and diminished demand for them in the thick of the Galwan valley conflict between the neighbouring countries. Furthermore, the stark contrast in import and export numbers has substantially brought down India’s trade deficit with China to nearly half of what it had been within the same period in the last financial year.

Nevertheless, China’s increase in consumption is a demonstration of its growing economy — while all other economies contract. The sudden shrinkage of the trade deficit is only a temporary occurrence under incredible circumstances. Therefore, such should not be misconstrued to be a manifestation of the effectiveness of domestic momentum against China.

India has collectively decided against receiving the short end of the stick — the government plans to dramatically increase investment in essential sectors such as the pharmaceutical industry over the next five years —for which India has been heavily reliant on China. Even with a heavy dependence on China for electronics, the path towards self-reliance is a slow one, yet with the appropriate embargoes being put in place, and policies being adopted to induce domestic production, it is certain to be of value to India.