‘Gender is a kind of haunting’: Jennifer Mills explores the queer potential of the ghost story in The Airways

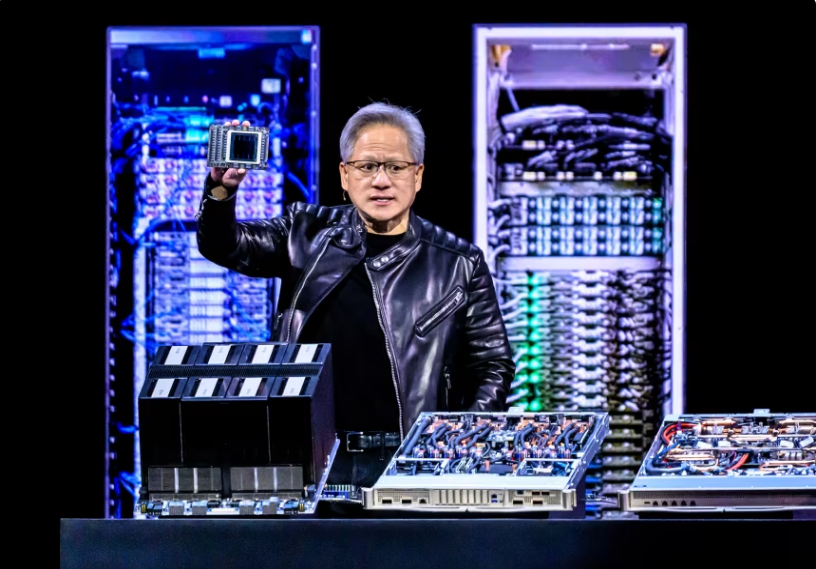

Show caption Jennifer Mills: ‘That unnerving horror realm has always fascinated me as a writer – the difficult places where we’re not sure what’s real and what’s not real.’ Photograph: Don Smith/Alamy Stock Photo/Alamy Stock Photo Australian books ‘Gender is a kind of haunting’: Jennifer Mills explores the queer potential of the ghost story in The Airways Miles Franklin-shortlisted author’s new novel follows a ghost who can inhabit different bodies in a reflective take on the genre Walter Marsh Sun 8 Aug 2021 18.30 BST Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

It’s hardly a spoiler to reveal that the chief protagonist of Jennifer Mills’s latest novel dies. It is fleeting, fragmented, violent, and over by page four – but it is not the end. “Evicted” from their own body, microbiology student Yun’s consciousness soon coalesces, unsteadily at first, into that of another person. And then another, and another, and another.

“It jumped into my body,” Mills says of the premise of The Airways, which first struck her during a residency in Beijing a decade ago. “I was on the subway one day, I must have just been daydreaming as I usually do, and this thought of a ghost that could jump between bodies almost jumped into me.”

Mills speaks to me over Zoom from Italy, where she finds herself in a limbo of her own after plans to relocate back to South Australia in time for the book’s launch were scuppered by Australia’s recently slashed overseas intake. “Having to appear at my own events in this ghostly digital form … the irony hasn’t escaped me,” she says.

Like her Miles Franklin-shortlisted 2019 novel Dyschronia – which used a slippery approach to time and memory to portray a small coastal town buffeted by ecological and economic collapse – the result is intriguing, if initially enigmatic and disorienting, as Mills puts her own inventive spin on the ghost story genre.

Australian writer Jennifer Mills, whose novel The Airways is out now through Picador. Photograph: Jennifer Mills

“One of the differences with The Airways is that I strongly identified with the ghost — and I wanted the ghost to win,” Mills says of Yun. “I think all ghost stories are about justice, and the restoration of order; ghosts often haunt people who have done violence to them, or they’re trying to right a wrong. But the purpose of most ghost stories is to make the ghost go away – and in this one, I was very keen on making this ghost survive, because I really grew to love them.”

The world becomes a “palace of human rooms” as Yun circulates from body to body, existing in an ambiguous space between benign possessor and passenger. Despite lacking a body of their own, they and the reader viscerally experience the membranous physicality of their hosts’ bodies in ways that are intimate and even invasive.

“That unnerving horror realm has always fascinated me as a writer – the difficult places where we’re not sure what’s real and what’s not real,” she says of the book’s “whizzy ride” through the tissue, touch and traumas of Yun’s vessels. “So it sits quite comfortably for me. My comfort zone as a writer sits in everyone else’s discomfort zone.”

‘The purpose of most ghost stories is to make the ghost go away – and in this one, I was very keen on making this ghost survive,’ Mills says.

There are also more everyday horrors on show, as Mills flits back and forth between Beijing and Sydney, before and after Yun’s death. Alongside Yun’s post-corporeal journey, we also follow the story of their one-time flatmate Adam, a self-described “good guy” despite mounting evidence to the contrary. In the years since Yun’s death near their Sydney share house, Adam has uprooted himself to China, where he lives the in-between life of an expat while generally seeming rather dead inside.

In writing Yun as a non-binary Chinese Australian now navigating a new liminal space between life and death, bodied and bodiless, Mills was less interested in narratives of violence or transition. “I knew that Yun was gender non-binary from the beginning, but I wasn’t sure if I could write that character responsibly,” explains Mills, who says she identifies as genderqueer, but is “a bit of fence-sitter” when it comes to fixed categories of identity.

The use of the pronoun “they” is both a signpost of Yun’s identity (one that’s barely remarked upon in the text) and a literary device that hints at the multiplicity of their co-existence in the bodies they inhabit. “I got excited about the literary possibilities of the singular ‘they’, and then this idea of plurality made so much sense – for the book to be in that voice,” Mills says.

I think all ghost stories are about justice, and the restoration of order

“They’re really aware of themselves as a potentiality in the beginning, which is why it can be read as a book of queer survival as well,” she says. “They’re aware of the lots of potential selves they could become, and the struggle is then to survive in the world in some way, find one that will fit, find one that you can be in.”

As the book hopscotches to its final destination, its many reflections on gender, biology, borders and binaries bubble to the surface. It’s a knotty kind of ghost story – and one that doesn’t need jump scares to pull readers out of their own skin.

“I was always drawing the conclusion for myself that gender is a kind of haunting that happens in our bodies – it’s a kind of possession,” Mills reflects. “Because you’re not fully in control of your gender, or how the world sees you.

“And maybe coming to terms with that, or to a peaceful place with that, was part of writing the book.”

• The Airways by Jennifer Mills is out now through Picador