Politicians should stop wasting time on doomed Olympic boycotts

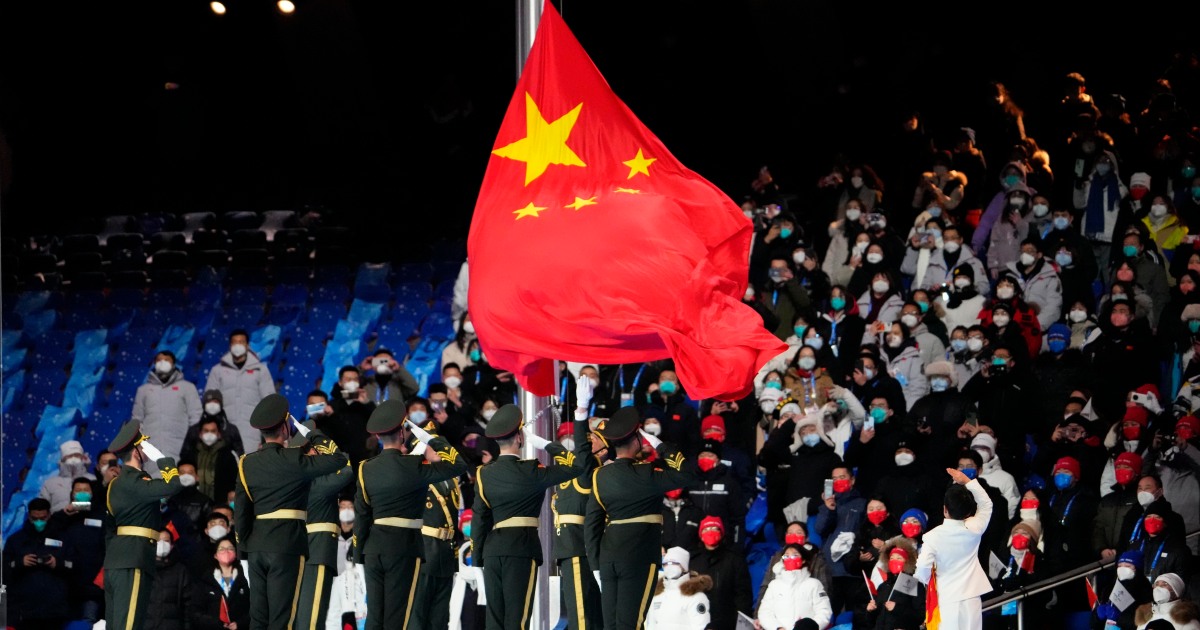

The ‘diplomatic boycott’ of 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, by the US and seven other countries, will most likely have no impact on China’s domestic policies.

I am a member of that generation of athletes that was shaped by the US and Soviet-led Olympic boycotts in 1980 and 1984. I placed seventh in the 1980 US Olympic Trials in track and field, in the pentathlon – in 1981, it became the heptathlon, while the top three made the Olympic team. But we knew before the trials started that none of us would actually be going to the Summer Olympics in Moscow. That was the closest I would ever come to realising my Olympic dream.

The US decision to boycott the 1980 Moscow games to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan made it clear to us that we athletes were nothing but pawns – that our government would celebrate us as heroes when we win but would also not hesitate to crush our dreams when it feels the need to make a political statement.

And we were not alone in our disappointment. More than 60 nations followed President Jimmy Carter’s lead and kept their athletes home in 1980.

In the end, the 1980 Olympic boycott, which killed the dreams of so many athletes across the world, did not achieve any of its goals – the Soviet Union did not pull its troops out of Afghanistan for another nine years, and despite all this posturing, Carter went down in history as a weak president.

The 1980 boycott, however, had one unexpected consequence. The generation of athletes who lost out because of this ineffective boycott grew cynical about governments’ efforts to make political statements through sporting events. As the years passed, they started to take up leadership positions in the international sport system and publicly took a stand against political interference in sports. One of these athletes was Thomas Bach, the current president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), who had publicly criticised the West German National Olympic Committee’s support of the 1980 boycott, which deprived him of the opportunity to defend his 1976 gold medal in team foil (fencing). Juan Antonio Samaranch, who became IOC president just after the 1980 Summer Olympics, meanwhile, worked throughout his 20-year tenure to persuade governments that boycotts are not politically effective, and only harm athletes. To top up all these efforts, some 20 years after the boycott, the US itself invaded Afghanistan and launched a military occupation that lasted twice as long as the Soviet Union’s, making the US position in 1980 seem somewhat ludicrous.

As a result, since the end of the Cold War, there has been a broad consensus among national governments and Olympic committees that boycotts don’t accomplish political goals, and only punish the athletes. The first post-Cold War Olympics, the Winter Olympics in Albertville in 1992, had universal participation, and in all the years since then, no nation has kept its athletes home while declaring that it is doing so as political protest. North Korea did not send athletes to Tokyo in summer 2021, but it gave the COVID-19 pandemic as the reason. Nevertheless, the IOC banned Pyongyang from the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, demonstrating that it would not hesitate to punish boycotting nations. Today, the only voices calling for nations to keep their athletes home, or the IOC to move the games to another country, are advocacy groups and a few politicians.

But in recent years, there have been attempts to stage different, more limited boycotts and protests around Olympic Games.

Before the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, US senator and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi called on President George Bush to “boycott the opening ceremony” as a protest against China’s human rights record, particularly the oppression of Tibetan Buddhists in Tibet. Human rights groups took up the idea and pressured heads of state worldwide to do the same. As a result, about 13 heads of state, plus the UN secretary-general, did not attend the ceremony. Most stated openly that they skipped the ceremony as an act of protest, but others offered different excuses. All these countries, however, sent other government representatives. Many of these same heads of state, along with some who attended the ceremony, also made a symbolic statement by receiving the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, as an honoured guest before the Olympic Games. President Bush, for example, attended the opening ceremony, but also awarded the Dalai Lama with the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor a few months before the games.

While these boycotts and political statements surrounding the Olympic Games did not harm the athletes like the boycott of 1980, they once again achieved very little – the Chinese leadership did not change its policies in Tibet.

Tibet was seldom mentioned when another campaign, this time for “a diplomatic boycott”, began in the run-up to the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics. By this time, the oppression of the Tibetan Buddhists had taken a back seat to the oppression of the Uighurs in Xinjiang.

The label of “diplomatic boycott” is new in the Olympic context. House Speaker Pelosi, who had led the calls for the “opening ceremony boycott” in 2008, used the phrase for the first time in summer 2021 when she called on Congress to keep official government representatives home, while sending athletes to the games.

As they had in 2008, human rights groups picked up the call and started pressuring governments across the world to do the same. Eventually, in December, the US and seven other countries announced their decision not to send government officials to the games “because of concerns about China’s human rights record”. A handful of other countries, meanwhile, did not send government officials, but did not explicitly frame this move as a boycott.

No matter from which perspective I look at this most recent “Olympic boycott” – that of an anthropologist who sees the grand sweep of human history, or that of an athlete who personally experienced an Olympic boycott – I reach the same conclusion: it will not work. Throughout Olympic history, moments of political grandstanding have come and gone with the political winds of the times, but the ideal of friendly national rivalries on a peaceful playing field has endured. There is no reason to believe the result will be any different in 2022.

He Zhenliang, China’s senior sports diplomat and first IOC member in the People’s Republic of China, once cited a Chinese proverb to describe the ineffectiveness of the political attacks on China’s efforts to host the Olympics: “The monkeys scream nonstop from the banks while the light boat has already passed by countless mountains.” As a China scholar, I agree with the general consensus among China experts that Biden’s diplomatic boycott will most likely have no impact on China’s domestic policies. If this indeed turns out to be the case, we can hope that our politicians will finally learn a lesson from history, abandon what appears to be an action doomed to failure, and seek out tactics that might be more effective. Perhaps the politicians would have more impact if they connect their actions with the more durable ideal of world peace instead of detracting from it with divisive rhetoric.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.