Whips, manacles and a bedazzled dildo – the ICA’s controversial show on sex work

Show caption Candy-coloured virtual sex dungeon … from This is Not For Clients by Yarli Allison and Letizia Miro (detail, click here to view full image). Photograph: Courtesy the artists Art Whips, manacles and a bedazzled dildo – the ICA’s controversial show on sex work Embroidered sex toys, dominatrix videos and a graphic rendering of a BDSM dungeon are among work by 13 artists in an exhibition that calls for decriminalisation Claire Armitstead @carmitstead Mon 14 Feb 2022 10.56 GMT Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

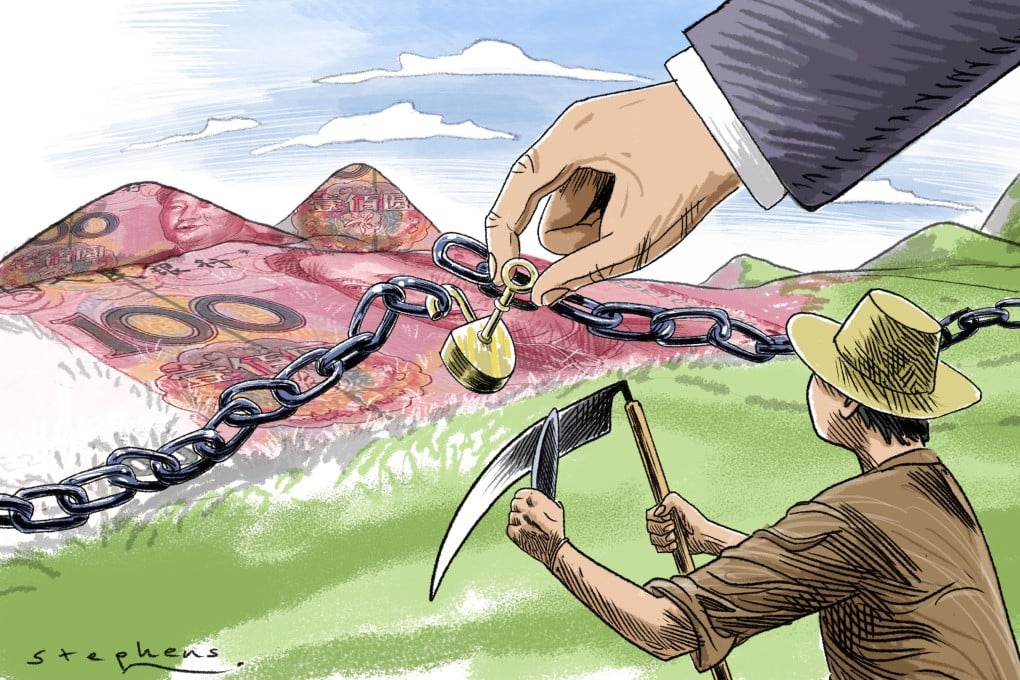

“This is Not for Clients”, proclaims the title of a two-screen video installation. The significance of these words soon becomes clear as two nine-minute films – one silent – simultaneously unspool the story of a sex worker’s journey from “princess” to “dominatrix” to “low cost”. The camera drifts around a candy-coloured virtual sex dungeon as a voiceover explains: “High volume, low price, in order to survive. I have passed for ever to the side of the a-normals, of the crazy, of the misfits. Only we know when we survive, dirty with their opinions.”

You can see why clients would not want to prick their consciences with this glimpse behind the scenes of their erotic fantasies. Letizia Miro, who wrote the text and performs in the film’s framing scenes, caters for such clients in her other life as an “unconventional libertine”. A London-based Catalan writer, poet and philosophy PhD, Miro quotes Virginia Woolf and the poet and novelist Ocean Vuong on her glossy website, which advertises her services as a fantasy girlfriend, “kinky companion” and “sensuality coach”.

Exploring the oldest industry … 1 x Triptych by Tobi Adebajo. Photograph: Courtesy the artist

When we meet via Zoom, Miro explains: “The website is client-facing, which means it doesn’t expose the complexities and darkness. Talking about precariousness is not sexy. My brand is very positive, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true. I’m a positive, empowered woman but I’m also struggling like everyone else to feel alive and to be financially independent in a capitalist system I did not choose.”

The work is a collaboration with Yarli Allison and the two are among 13 international artists who were selected from 90 respondents to an open call submissions for the polemical exhibition about sex work, which opens this week at the ICA in London. From moving image to sculpture, from gaming to comics and embroidery, Decriminalised Futures sets out to explore the many facets of the world’s oldest industry, while making a case for it to be fully decriminalised.

Technically, Allison points out, simply by collaborating on a sex work-related subject, she and Miro could fall foul of the UK’s sex trafficking laws. “Even as a videographer,” she says, “I could get in trouble, right? Because I’m in the same room – and no two women are allowed to be in the same room.” Miro adds: “It’s insane, because it forces women to work alone in unsafe situations – if there’s a bad client, you can’t go to the police.”

The exhibition was the brainchild of curators Elio Sea and Yves Sanglante, and grew out of a weekend conference in 2019 celebrating the 10th anniversary of Swarm (the Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement) . “There’s a lot of political organising around sex worker rights, and creative stuff, so we thought it would be great to create a space for it that was wider,” says Sea, who comes to the project from a background in community advocacy, while Sanglante’s expertise is archiving and curating. “We know, from sex workers, that their lives are complex,” adds Sanglante. “Sex worker rights are a key intersection point of disability and healthcare, migration and borders, gender and work. We felt an exhibition might be a way to show that complexity.”

From Decriminalised Futures … an embroidery piece by Hanecdote. Photograph: Courtesy the artist

Although the exhibition has yet to be fully installed – it will take over two storeys of the ICA, which sits in a grand 19th-century terrace just down the road from Buckingham Palace – there is beauty in the pieces that are viewable in advance. London-based Hanecdote uses fine embroidery to depict a sex worker’s dressing table: to one side of the clutter of makeup, masks and sex toys is a pile of books with such titles as Action, Safety, Community. Khaleb Brooks, a Chicago-born artist who has a residency at Liverpool’s International Slavery Museum, has made three arresting lifesize self-portraits in linocut, depicting themself before, during and after a sex session.

Lifesize self-portrait … Photo of the Session (3 3) by Khaleb Brooks. Photograph: Courtesy the artist

The artists, who were selected by an independent panel, did not have to disclose whether they were involved with sex work. “In the public view,” says Sea, “there’s often this conflict. Either you say you’re a sex worker and people think, ‘Oh, you’re a victim, your voice can’t be trusted.’ Or you say you’re not a sex worker, then people tell you, ‘Oh, you don’t know what you’re talking about. You’re not an authentic voice.’”

For Miro and Allison, as for many, the boundaries are blurred anyway. While Miro created the “semi-fictional documentary” of This Is Not for Clients, Allison was responsible for the filming and the surrounding installation, which will fill a whole room. Her bright, freeform graphics make the whips and manacles of a BDSM dungeon look like soft-play toys. From Hong Kong, though born in Canada and now based in Paris, she came to the project via an interest in east Asian and queer porn. “At the beginning,” she says, “I thought gay porn is porn and my art is my art – I saw them as separate. But now I realise that making queer porn, and queer tattooing in queer spaces, is just as consensual as any other artwork in my practice”.

It was a tattoo that brought the two together. Miro holds her arm up to show an image, made by Allison, of a woman emerging from a box. “That’s me getting out of my PhD,” she says. She has published her writing under several different names and would love to bring them all together in an anthology one day, but has not yet dared to do so for fear of losing both her work and her family.

Creative protest … from Mythical Creatures by Liad Hussein Kantorowicz. Photograph: Aviv Victor/Liad Hussein Kantorowicz

Because of the particular interests of the selection panel – which included artists, film-makers, writers and curators – the exhibition is dominated by artists who operate in a queer space. Among them is Aisha Mirza, a DJ, stripper and columnist for Gal-dem magazine, who recently featured in a British Vogue profile of three gender non-confoming trendsetters. Mirza, who is bipolar, describes their installation – the best dick i ever had was a thumb & good intentions – as a meditation on the intersection of pleasure and sacred spaces with mental health and selfhood: “I got involved in the exhibition by answering the callout. I was working as a stripper at LGBTQ club Harpies at the time, and had a lot of thoughts and feelings about that experience, so it seemed like a good match.”

Mirza, who lives on a houseboat in east London, has worked as a dominatrix. “With chronic mental health difficulties, sex work has seemed more appealing and attainable than many other jobs. If I can make three months’ rent kicking a man in the balls for 30 minutes, why wouldn’t I? Due to my privileges and safety nets, I’m able to choose what jobs I want to do. I’m able to have firm boundaries around what’s comfortable for me. This is not the norm.”

Comic appeal … from Unsustainable by Annie Mok and Danica Uskert from Decriminalised Futures. Photograph: Courtesy the artists

Mirza is referring to the dark side of a global industry that exploits and traffics vulnerable people. The exhibition doesn’t shy away from this, its curators say. “There’s an understanding of what it means to be exploited,” says Sea, “But there’s a cultural preoccupation with talking about trafficking as soon as we talk about sex work, when trafficking is a form of exploitation that can be found at high levels in many sectors, including agriculture, domestic work and construction. There was a report just the other day about the levels of trafficking within farming and domestic labour.”

Mirza is more militant. “As we know, sex work is the oldest profession. It needs to be respected, and brought out of the shadows for the safety of people engaging in it. It’s beyond disgusting that politicians and bankers make decisions every day that endanger and harm poorer and marginalised people – while also using the services of sex workers. Yet they are respected and rewarded, while sex workers are reviled and considered sub-human, not even worthy of basic rights and protection. I want the moral hysteria around sex work to die because it is so boring and hypocritical and dangerous that it hurts.”

Mirrors are a recurrent motif through the artworks, whether at the centre of Hanecdote’s exquisitely embroidered dressing table, or on the walls of Miro and Allison’s dungeon. Mirza – who uses a large ornate one to lure people into viewing themselves alongside a collection of objects personal to the artist, from zines and meds to a “bedazzled dildo” – sums up this preoccupation with the two-way gaze. “I wanted people to see themselves, in both a ‘You’re welcome’ and a ‘You’re implicated’ kind of way.” Dirty opinions will have to be parked outside the door.