Taiwan’s amateur fact-checkers wage war on fake news from China

Taiwanese civil society organisations are working to combat misinformation instead of leaving the job to the government.

Taipei, Taiwan – As China flexed its muscles with large-scale military exercises off Taiwan last month, Billion Lee was busy countering an onslaught taking place against her home online.

False stories claiming that the United States was preparing for war with China, that China was evacuating its citizens from Taiwan, or that Taiwan had paid millions lobbying for US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s recent visit to the island spread across popular social media platforms Facebook and LINE.

A fabricated photo of a People’s Liberation Army soldier monitoring a Taiwanese navy vessel through binoculars was disseminated by Chinese state-run media Xinhua before being picked up and circulated by international outlets such as the Financial Times and Deutsche Welle.

While government agencies rushed to issue clarifications, urging civilians to take care to avoid falling victim to information warfare by “hostile foreign forces,” much of the work combating the false narratives fell to amateur debunkers of fake news such as Lee, who co-founded fact-checking chatbot Cofacts in 2016 with the open-source g0v community.

“We have a saying: Don’t ask, why is nobody doing this? Because you are nobody. If nobody did this before, you are the one to establish something,” Lee told Al Jazeera.

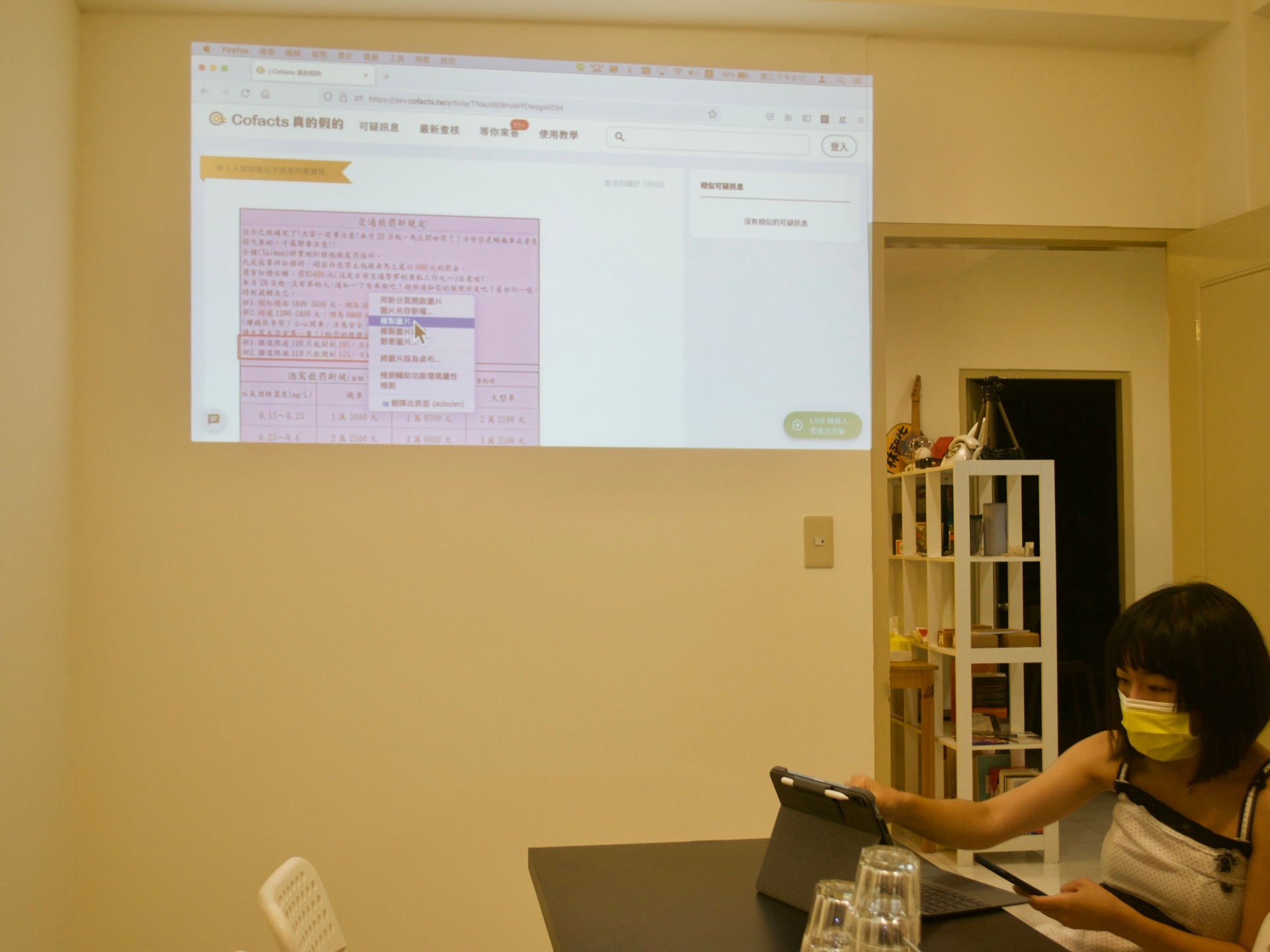

Cofacts automatically responds to fake or misleading messages circulated on the LINE messaging app with a sourced report. Fact checks are written and reviewed by a group of more than 2,000 volunteers, including teachers, doctors, students, engineers and retirees – anyone who wants to be a fact-checker can become one.

The idea is to make reliable information accessible to everyone, according to Lee, in part by giving the power of fact-checking to Taiwan’s civil society rather than leaving the job to the government. Cofacts is just one of a host of Taiwanese civil society organisations that believe the primary responsibility for combatting disinformation rests with its citizens.

“All of our civil society groups, we kind of have a division of labour,” Puma Shen, the director of DoubleThink Lab, a research group that focuses on Chinese influence campaigns in Taiwan and around the world, told Al Jazeera.

“Some of them focus on fact checks, some of them focus on workshops, and we focus on the accounts’ activities.”

For Shen, Taiwan’s democratic values, including freedom of speech, are a crucial part of the solution to state-backed disinformation.

“If you really want to persuade the public, I think the best way is that the government has to tell the public: ‘Hey, we’ve got a huge issue about fake news and disinformation.’ But then let the non-profit organisations take over,” he said.

Disinformation campaigns, usually in the form of conspiracy theories, propaganda, and fake news stories distributed by content farms, bots, and fake accounts are considered “cognitive warfare tactics” by the Taiwanese government.

Many campaigns specifically aim to foster distrust of the US – which is one of the island’s strongest diplomatic and military backers despite not officially recognising Taipei – a tactic that may be working given declining faith among Taiwanese that the US would come to their aid in the event of a war, Shen said.

In March, the Digital Society Project identified Taiwan as the No 1 target for foreign governments for the spread of false information during the past nine years. According to a report produced by the National Bureau of Asian Research last year, Taiwan acts as a testing ground for Chinese information campaigns before they are implemented elsewhere, and is an important node in information dissemination to regions such as Southeast Asia.

Information warfare is as old as the cross-strait tensions between Beijing and Taipei, but the real-life consequences of the unchecked spread of disinformation in 2018 incident served as a wake-up call to the government and civil society alike.

That year, Su Chii-Cherng, a Taiwanese diplomat in Japan, died by suicide after Chinese media outlets distributed a fake story claiming that he failed to help Taiwanese citizens escape during a typhoon there. Many also believe Chinese propaganda and disinformation heavily influenced Taiwan’s midterm election results that year.

Concern about the spread of disinformation was also heightened that year due to a series of referendums on controversial topics, including nuclear power and LGBTQ rights, that stoked deep divisions within society.

“There were parents kicking children out, couples breaking up because they have different points of view. And then we started to think about, what did we miss? We thought about the filter bubble and how the algorithm puts us in an echo chamber,” Melody Hsieh, the co-founder of Fakenews Cleaner, an NGO that leads media literacy workshops with Taiwanese civilians, told Al Jazeera.

The events of 2018 spurred the launch of Fakenews Cleaner, among other anti-disinformation organisations. Since its founding, the group has accumulated 160 volunteers and hosted nearly 500 activities across Taiwan, from lectures in classrooms and nursing homes to public outreach in parks and at festivals.

Its main audience are Taiwanese aged 60 and older, a demographic seen as particularly susceptible to health-related misinformation and phishing scams.

“Sometimes we host some classes with elders and some will become very angry and stand up and say: ‘Why didn’t the government do anything? They should have an organisation to stop the content farm’. The older generation has been through the White Terror,” Hsieh said, referring to the repression of civilians on the island during the military-dictatorship era prior to democratisation in the 1990s.

“I tell them if we create a law or [government] organisation, if different parties get in power, maybe they can press you just like the White Terror … We say the most important thing is to learn how to protect themselves.”

Attempts by the government to crack down on the spread of fake news have been deeply unpopular because of Taiwan’s democratic values, but also because of its authoritarian past. One of the most common – and controversial – laws used today to punish individuals or groups for disseminating false information, the Social Order Maintenance Act, is a remnant of Taiwan’s martial law period.

Taiwan’s government continues to introduce bills aimed at increasing its control over information, a majority of which fail to become law. In June, Taiwan’s National Communications Commission introduced the Digital Intermediary Services Act, which would establish obligations and provisions for certain platforms with large audiences and streamline the process of removing illegal content.

The proposed law has been hotly debated; one poll circulated on Facebook by Taiwan’s opposition party, the Kuomintang, found that a majority of people opposed the bill, which has since been suspended.

Still, many Taiwanese believe the government does have an important role to play in the information war as long as it refrains from policing content — especially given the workforce and funding constraints faced by all-volunteer non-profit organisations.

Some experts argue the government should focus on improving media literacy education in schools, cracking down on phishing scams, and improving data privacy.

As cross-strait relations intensify, China’s information warfare tactics could outgrow traditional debunking or fact-checking methods used by the government and NGOs, said TH Schee, who has worked in Taiwan’s internet sector for 20 years.

Footage of Taiwanese soldiers throwing rocks at a Chinese civilian drone last month was real but was disseminated “not only to test our response, but also to create false information by editing video clips [and] disseminating them in the online community” in an attempt to create divides and discredit Taiwan’s army, the Ministry of National Defense wrote in a statement.

“Information warfare was all about disinformation in the past four years. But now you’re seeing real information with different interpretations that could cause harm or distrust in your government,” Schee told Al Jazeera.

“That will keep growing and growing, and I don’t think the government has yet figured out a way to deal with real information that is causing harm.”

Schee said getting ahead of the information war should be a whole-society effort that takes a preventative, rather than reactionary, approach. For non-governmental groups, that could mean collaborating directly with journalists to create a better media environment, he said, while the government might have to take civilians’ privacy more seriously.

“By introducing stronger privacy and protecting the user from having their online behaviour or data being manipulated or monetised, that would be a very good start,” he said. “This might not sound that direct, but it’s about protecting your citizens from the harm of disinformation without censoring the content.”