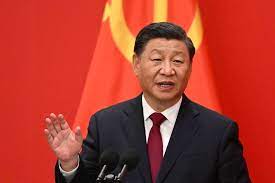

XI PICKS NEW TEAM ENSURING NOBODY LEFT TO CHALLENGE HIM

The undignified manner in which former Chinese president, Hu Jintao, was escorted out of the 20th Party Congress in the presence of his successor, Xi Jinping, tells the story of the latter’s consolidation of party power after getting the third term.

One may not be entire sure given the secrecy of the Chinese Communist Party, but the fact is Xi may have purged the party of the last murmur of dissent before the Congress began. The world will never know Jintao’s sin for making a spectacle of his unceremonious ouster, but everything in China is linked to the supreme leader not brooking dissent in any form.

Recall how the situation was different in 2012. Jintao was lauded publicly when he relinquished power and stepped down as CCP leader and paved the way for the entry of Xi Jinping. Subsequently, he kept to himself though he was associated with many communist groups considered dissenters by Xi loyalists. Many of his former allies have been arrested in Xi’s purges, most notably his chief aide Ling Jihua in 2015. Hu was associated with a power network of former leaders, like himself, of the Communist Youth League; that faction appears to have been effectively destroyed.

Regarding Jintao’s expulsion from the Congress, western media is exploring the possibility that “it was planned, and we just witnessed Xi deliberately and publicly humiliate his predecessor—possibly as a precursor to wielding the tools of party discipline, followed by judicial punishment, against him”. This would be an extraordinary move but “one that rammed home the message of Xi’s absolute power—something reinforced by the rest of the Party Congress, which just solidified Xi as the “core” of the party in the (often modified and mostly symbolic) Chinese Constitution and where he has been front and center as he takes an unprecedented third term”.

A Foreign Policy analysis explained: “Bear in mind that Xi used extremely harsh language in his opening work report to describe the situation within the party when he took over, speaking of a ‘slide toward weak, hollow, and watered-down party leadership in practice’, though without mentioning Hu or others by name. (Hu’s contribution to Marxist theory, the Scientific Outlook on Development, also got a token mention in Xi’s speech.) Humiliating Hu in this fashion would also send a clear signal to the ‘retired elders’, the former high-level leaders who long remained a force within the party, that Xi’s power was unbound. In that case, Li Zhanshu’s gesture of offering assistance to Hu would have been one of instinctive—but dangerous—kindness toward a former colleague.”

The new Standing Committee of the party now comprises of China’s seven most important leaders led by Xi. The six are those personally chosen by the president and are immensely loyal and close to him. Dissent has no place in this peculiar ‘democratic’ set-up.

Names of senior leaders doing the rounds in the run-up to the Congress nowhere figured in the final list. They included two serious contenders for the standing committee, Hu Chunhua and Wang Yang. Known for being relatively pro-reform with a record of experimentation, both were excluded from power altogether. Wang, who served on the previous Standing Committee, didn’t even make it onto the Central Committee list of more than 200 officials, whereas Hu was excluded from the 25-person Politburo.

The age of the men on the new Standing Committee is also significant. The youngest, Ding Xuexiang, 60, is nine years younger than Xi—making him barely plausible as a candidate for leadership in the highly unlikely event that Xi retires in five years. The rest of the group is so close to Xi’s age that they certainly couldn’t replace him. When Xi and former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang were added to the Standing Committee in 2007 at ages 54 and 52, respectively, they were held up as shining examples of youthful leadership.

To reduce the chance of political challenge to Xi, all the chosen members are political underlings and weak, and have no family connections in the party that they could have depended on in the future. The lone exception is Wang Huning, a nationalist theorist who was close with previous leaders.

Among the committee members, Li Qiangwill technically be the most important of those individuals appointed to the Standing Committee, but in practice, he may be the most ‘powerless’. As the second figure to follow Xi onto the stage last week, he will succeed Li Keqiang as premier when he formally retires in March.

Past premiers, such as Zhou Enlai and Wen Jiabao, used the position to put a human face on the leadership. But Xi completely eclipsed Li Keqiang, whose successor will likely be equally overshadowed. Li Qiang’s career was made when he started working under Xi in Zhejiang’s Standing Committee in 2005. He has since been the governor of Zhejiang (and later, Jiangsu) and followed Xi on foreign tours.

Unusually for a premier, according to Foreign Policy, “Li Qiang doesn’t have any central government experience, putting him further under Xi’s control”. He also has an immediate political weakness: As Shanghai party secretary since 2017, Li Qiang was responsible for implementing the city’s catastrophic lockdown this year. Before then, he was a relatively business-friendly leader with a light touch when it came to COVID-19 policies.

Zhao Lejialso served on the previous Standing Committee, where he was the youngest member. Zhao is the definition of a safe pair of hands, a party man with a steady career and a record of success at the provincial level who has spent the last five years running the CCP’s feared internal Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. He doesn’t seem to have played a major role in leading individual cases, instead acting as an all-around fixer.

Wang Huningis probably the most interesting of the six members; he also served on the previous Standing Committee. A major political theorist, he leads a small working group that enforces CCP ideology. Occasionally called “China’s Kissinger,” Wang was also a favorite of previous leaders Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao,” a nationalist theorist with a vision of China as providing an authoritarian alternative to a weak West”.

Cai Qi is considered Xi’s longest-standing political friend. The two leaders have worked together since Cai joined Xi in a Fujian provincial department in 1985. Xi has clearly been Cai’s boss since the 1990s, but the two men remain close. Cai is a total Xi sycophant, having trailed him from post to post and vigorously promoted his role as the core of the CCP. Cai’s latest job was as party secretary of Beijing, seemingly so Xi would have him close by. His years in power have seen the destruction of the capital’s cultural life and a war against the poor, including the evictions in the winter of 2017 that left hundreds of thousands of homeless people on the cold streets, leading to an embarrassing public walk back.

Ding Xuexiangis little more than Xi’s chief of staff—an effective administrator who started working with him in 2007 and has remained close by ever since. He is very smart, very effective, and has few connections or pull of his own, making him a perfect Xi ally.

Lastly, Li Xi is taking over the CCP’s disciplinary unit from Zhao Leji. Like the others, he is a long-term associate of Xi, with the two men often photographed together. Those ties go back to one of Li Xi’s early jobs working for a close associate of Xi’s father.